Audubon Prints

Audubon’s Insects

An Investigation of the Bugs in Audubon’s Birds of America

Audubon’s Birds of America was revolutionary for several reasons, including his dramatic representation of birds mired in their natural environment. His compositions frequently depict male, female, and juvenile birds of the same species positioned in characteristic postures and carrying out idiosyncratic activities. In addition to the delineation of the bird’s natural environment by means of local foliage, dietary clues are often included in the form of insects, small mammals, or arachnids that serve as sustenance for the particular species. These insects lend a sense of drama, dynamism, and narrative to the compositions and provide insight into the bird’s native ecosystem and gustatory proclivities. However, in addition to instructing us on the dietary and habitational aspects of the bird species, Audubon’s insects in Birds of America offer unique insight into the creation of the prints themselves and the various collaborative efforts that brought them into being.

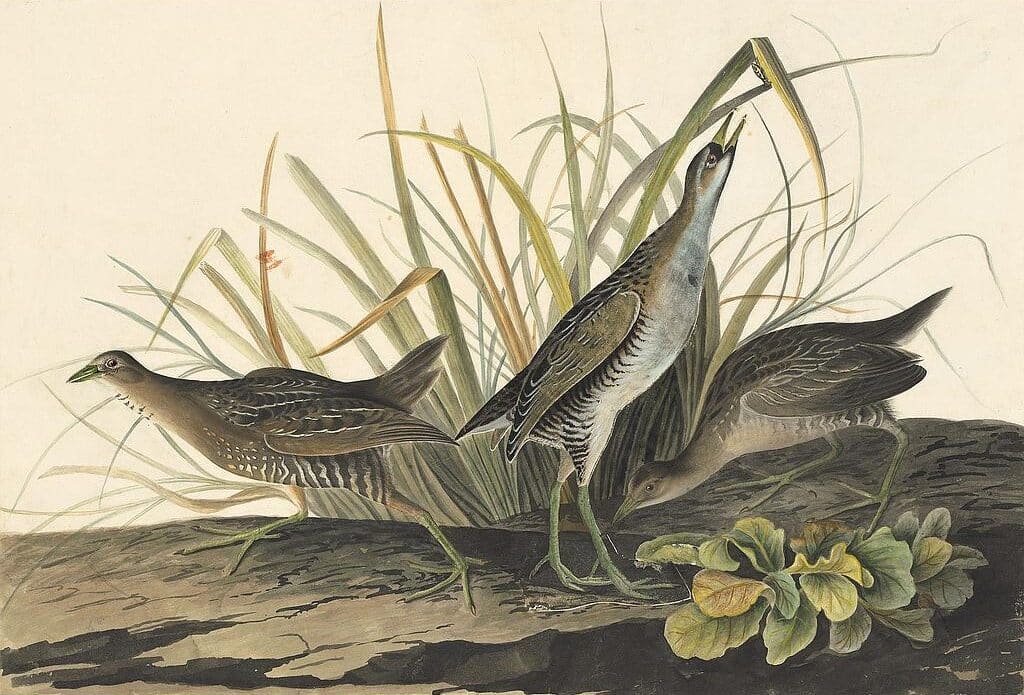

The typical functions of insects as points of animation and stylized nutriment in Audubon’s compositions are highlighted in the Pl. 327 Shoveller Duck. In this print, the male and female ducks lunge for a vibrant green beetle crawling along a sprig of swamp grass. The two birds’ bodies are oriented around the point of interest: food. Similarly, in Pl. 205, the Virginia Rail, and Pl. 233 the Sora a similar compositional blueprint is reiterated with the insects as protagonists of movement and narrative complexity.

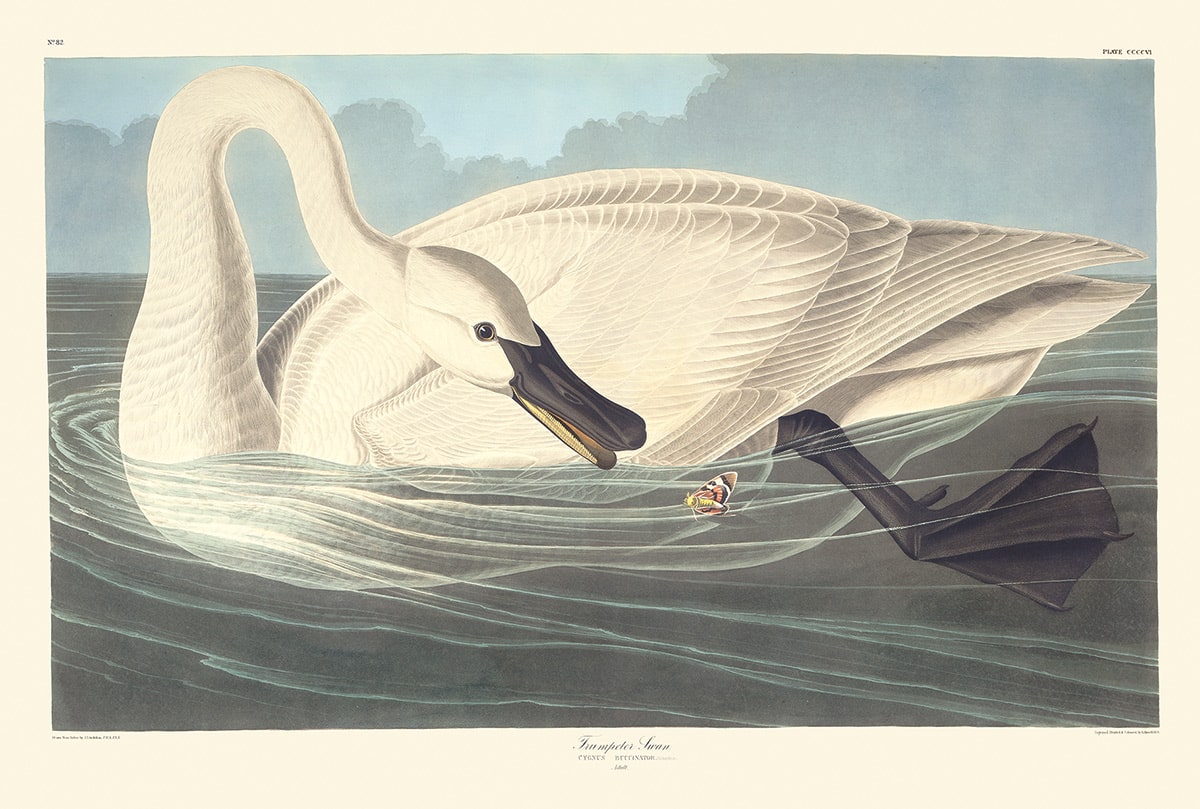

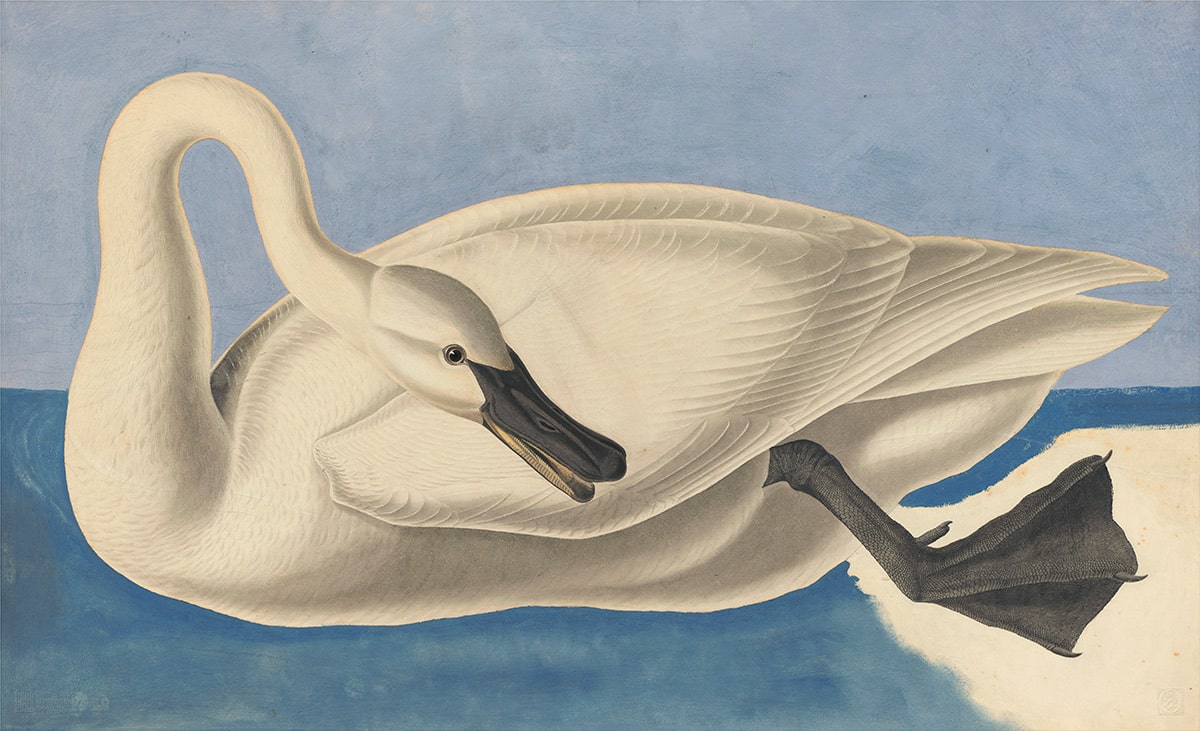

Audubon Havell Edition Pl. 406, Trumpeter Swan

Additionally, the insects offer insight into the creation and development of the prints themselves. Take for example Pl. 406, the Trumpeter Swan which depicts a life-sized adult swan gracefully arching its neck to address a lifeless orange underwing moth (Archiearis parthenias) floating on the surface of the water. Following his typical schema, Audubon’s artwork captures the species in its environment and with an indication of its dietary preferences; in this case, the moth. However, this moth species is not native to America but instead can be found readily in England, where the print itself was produced (Wagner 2019).

When we examine Audubon’s watercolor of the Trumpeter Swan, it becomes evident that the addition of the insect was not of Audubon’s doing but rather a later addition to the composition. In the watercolor, we find the solitary swan floating in an unfinished composition of sky and water with no moth to be found. It is likely that Robert Havell Jr., Audubon’s London printmaker, made the creative decision to add the moth as a focal point for the composition and an explanation for the bird’s arching posture. This explanation for the depiction of an exotic moth species is not unreasonable for Audubon delegated a significant degree of creative control to Havell, as well as to his assistants George Lehman, Maria Martin, and Joseph Mason.

Another interesting plate is Plate 82 The Whip-poor-will. This print contains three distinct species of Lepidoptera, identified by entomologist and biology professor James Wagner in his article “The Bugs of America 1826–1838” as a cecropia moth (Hyalophora cercropia), a female Io moth (Automeris io), and a large caterpillar of Abbot’s sphinx moth (Sphecodina abbottii) (Wagner, 2019). These insects lend the composition a sense of narrative dynamism as we watch the frenzied male whip-poor-will lunge, beak agape, at the cecropia moth. Likewise, one of the perched female whip-poor-wills hastens to inspect the caterpillar. Through the animating addition of the insects, Audubon relays the boisterous disposition of the birds and emphasizes its unique beak and rictal bristles that aid in marshaling prey into its waiting bill (Wagner 2019).

In his watercolor of the Whip-poor-will, Audubon notates the identity of the insects indicating a knowledge of natural history beyond birds. In this instance, he identifies the moths by their sex and species names: “Male”; “Saturnia Cecropia”; “Male/Bombyx[?] Io.” However, when examining this watercolor, Wagner explains that “Plumose antennae are a common distinctive characteristic of male moths, because they use them to detect the pheromones of female moths; however, both sexes of cecropia moths possess plumose antennae, although the males’ antennae are larger. It is clear that the Io moth with the thread-like antennae is a female, contrary to Audubon’s identification” (Wagner, 2019). While Audubon was adept at identifying the sex of bird species, he had not cultivated the same acumen in the realm of entomology.

Though Audubon frequently depicted the insects in his compositions, several of them can be attributed to his assistants as is the case in Plates 198 Swainson’s Warbler, Pl. 355 Seaside Sparrow, and Pl. 359 Say’s Phoebe, Western Kingbird, Scissor-tailed Flycatcher which were rendered by Maria Martin, the second wife of Audubon’s close friend John Bachman. In fact, Audubon spoke highly of her creative ability stating; “Miss Martin with her superior talents, assists us greatly in the way of drawing; the insects she has drawn are, perhaps, the best I’ve seen” (Audubon, 1833). In several instances, as Wagner observes, the presence of insects in Audubon’s artwork signals the collaborative effort of his assistants in bringing the artwork into its final form (Wagner 2019).

In conclusion, the insects portrayed in Audubon’s prints are more than mere decorative morsels. They are points of action and imbue the compositions with drama and narrative. Likewise, they offer valuable insight into the dietary habits and ecological habitats of the birds. Moreover, the inclusion of certain insects illuminates the creative relationships between Audubon and his collaborators in the making of Birds of America.

Works Cited:

James Wagner, The Bugs of America 1826–1838, American Entomologist, Volume 65, Issue 4, Winter 2019, Pages 238–249, https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/tmz066