Botanical Art

Part 2: The Influence of Scientific Modalities of Perception and Representation in Merian’s Artwork

An examination of Merian’s artwork in light of 17th-century scientific standards of perception and illustration

As a counter perspective to our previous article Examining the Art of Maria Sibylla Merian through the Lens of 17th-century Dutch Still-Life Painting, which discusses the influence of fine art in Maria Sibylla Merian’s folio Metamorphosis, this article will examine her prints in relation to the scientific modalities of representation and perception in 17th-century Europe.

To begin with, aspects of Merian’s artwork demonstrate her engagement with the schematic mode of representation popular in scientific illustration at this time. As a self-trained entomologist, seasoned artist, and pioneering explorer, Merian’s approach to her artwork was multidisciplinary and drew from the cultural, artistic, and scientific influences around her in addition to her own empirical observations. Additionally, a new mode of perception was introduced to Holland in the early 1600s in the form of the microscope. This device impacted the way Merian perceived the natural world and allowed her to operate on more than one scale which is evident in a number of her prints. While recognizing that Merian’s artistic approach to rendering elements of the natural world was entirely innovative, this essay seeks to identify echoes of a scientific tradition of perception and illustration in a number of her prints from the Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname.

Ferrante Imperato, Dell’Historia Naturale (1599), the earliest illustration of a natural history cabinet

In 17th-century Holland, scientists studied natural history by collecting elements of the natural world such as birds, plants, insects, shells, etc. which they described, preserved, and had drawn. These preserved specimens were kept in collections, many of which were prompted by an interest in botany or medicine. Many of these items were kept in cabinets of natural curiosities which featured an assemblage of disparate preserved forms of naturalia ranging from stuffed crocodiles, to dried herbs, to sea shells. The items were divorced completely from their ecological context and placed in these cabinets for observation and examination. This collecting practice significantly informed Dutch scientific illustration which tended to depict groups of specimens together with little regard for their relative scale or original environmental context.

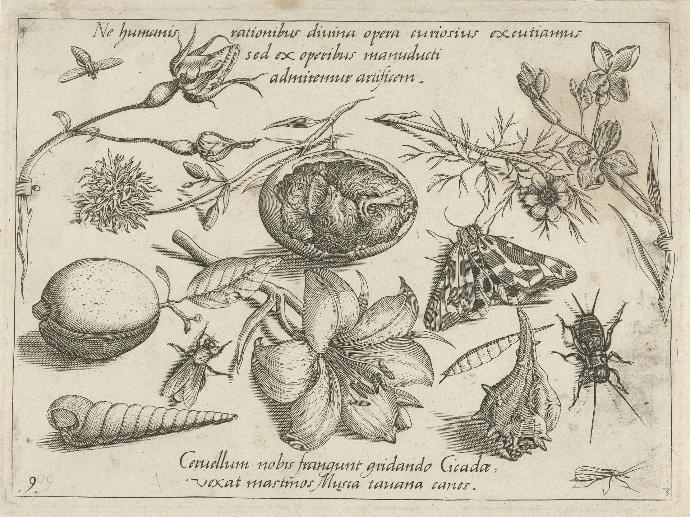

Insecten, planten en schelpen rond een kuiken in een ei, engraved by Jacob Hoefnagel, after Joris Hoefnagel, 1693 – 1726

A schematized form of scientific illustration developed and was greatly informed by the contents and arrangement of these cabinets and collections. For instance, this engraving by Joris and Jacob Hoefnagel captures a bricolage of unrelated specimens. An unhatched egg, insects, flowers, shells, and fruit pepper the page and make for a symmetrical and aesthetically pleasing composition. However, the engraving is void of any contextual indication of the specimen’s origin or relation to a broader ecosystem. Rather, they are presented as singular relics to be admired.

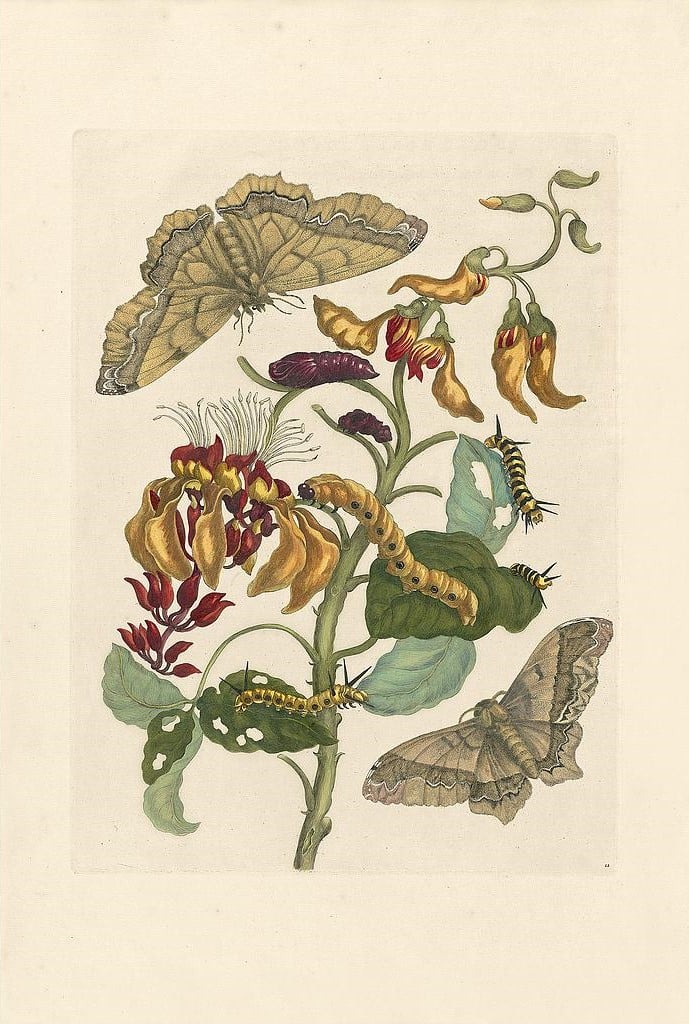

Pl. 11, Coral Tree with Emperor

This print is characteristic of Merian’s innovative approach to depicting insects as part of a broader ecosystem.

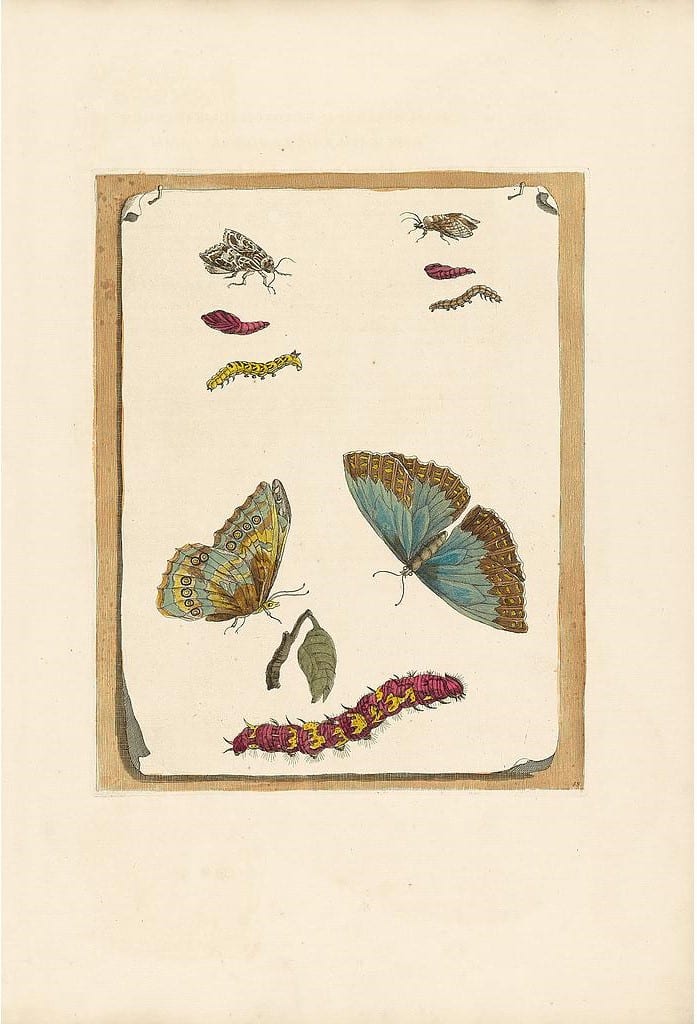

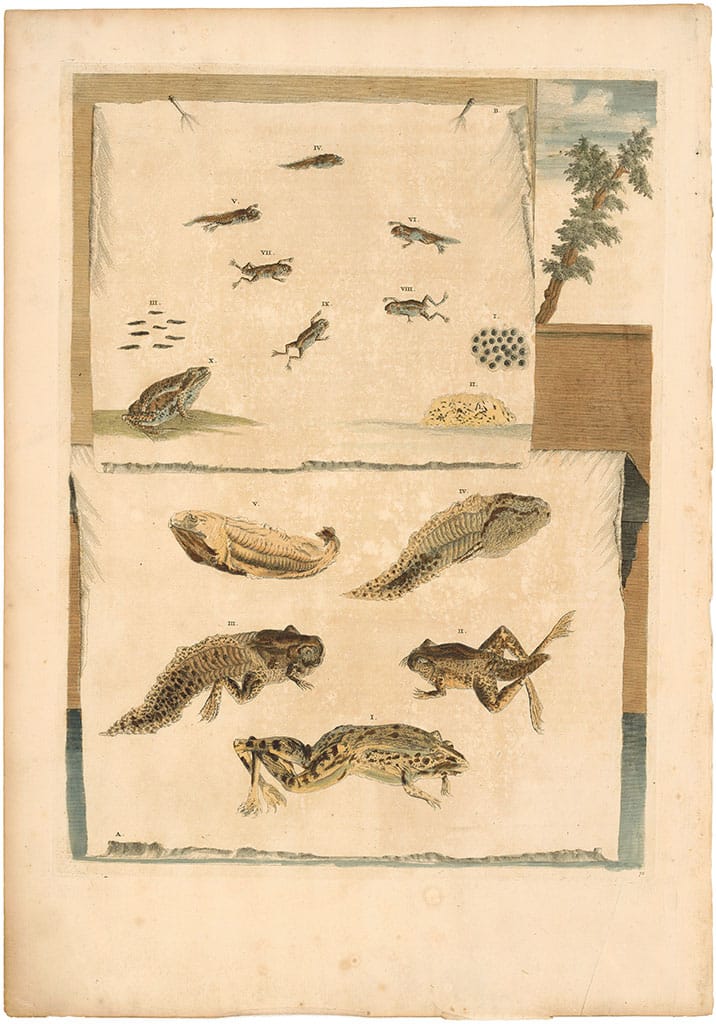

While most of Merian’s prints from Metamorphosis stand in stark opposition to this practice and instead show the insects and amphibians enmeshed in their native habitat, there are several exceptions to Merian’s typical manner of depicting insects that demonstrate an alliance with the schematic format of scientific illustrations. For instance, Pl. 68, Heather Butterfly and Pl. 71, Frog Metamorphic Stages indicate a strong familiarity with the unofficial standards of scientific illustration in which related and unrelated organisms are depicted in detail against a sparse background.

Merian Pl. 68, Heather Butterfly

Merian 1726, Pl. 71, Frog Metamorphic Stages

Here Merian creates a trompe l’oeil or optical illusion by depicting various insects and amphibians on a delineated sheet of paper. The vacant background allows the viewer to focus solely on the specimens depicted and the metamorphosis taking place but provides little context as to their native habitat, dietary tendencies, or the surrounding ecosystem. Rather, the specimens are grouped together and suspended as though curiosities in someone’s collection.

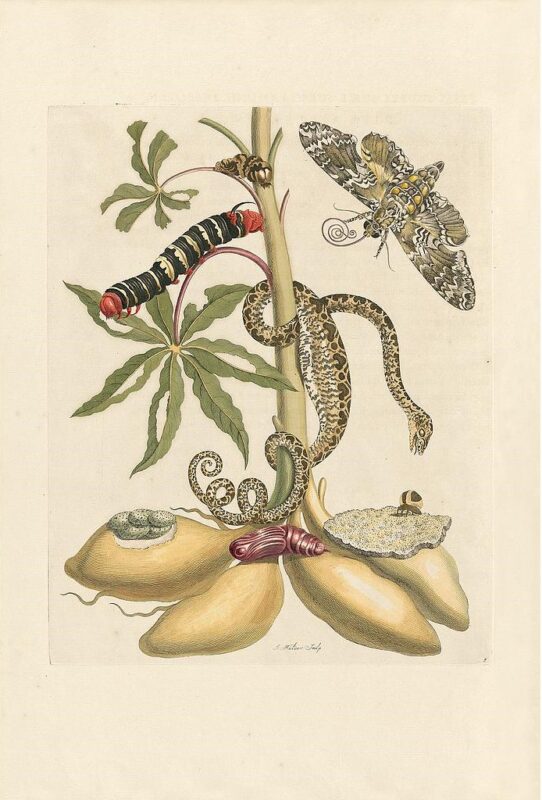

Furthermore, in several of her prints, Merian places emphasis on the roots of plants which demonstrates her familiarity with the contemporary standards and uses of botanical illustration. In his book Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration, Gill Saunders explains how “Roots and underground parts of plants were often of medical value to the herbalist and the apothecary, and knowing this, the artist illustrating a herbal invariably gives them as part of his account of the plant” (Saunders 1995, 14). This is evident in Merian’s Pl. 5, Manioc Root, Snake which features the bulbous root of the South American plant.

This particular print likewise visualizes Merian’s familiarity with scientific technology, namely the microscope, through her acute attention to detail and incorporation of more than one scale. While the insects are depicted at or close to life size, “The plant details are radically diminished in size,” (Viktoria Schmidt-Linsenhoff, “Metamorphoses of Perspective. “Merian” as a Subject of Feminist Discourse”, p. 215) Moreover, the boa constrictor that sinuously winds around the base of the Manioc plant has been reduced to comically minute proportions. This melding of relative size indicates Merian’s flexibility in visualizing the natural world around her on more than one scale. It is not hard to imagine that the microscope played a role in her ability to perceive the specimen as separate from its relative scale to her.

Merian was knowledgeable of much of the discourse taking place in the scientific community and contributed greatly to the study of entomology. In fact, Merian was the first to visually document the process of insect and amphibian metamorphosis. Moreover, she did so at a time when spontaneous generation, “the supposed production of living organisms from nonliving matter,” was perceived as a reasonable explanation for the “apparent appearance of life in some supposedly sterile environments” (Oxford’s English Dictionary). Thus her contribution to science was pioneering and invaluable.

To read Part 1 of our essay series on Maria Sibylla Merian, please visit the link below.