Birds and Animal Art, Botanical Art, Information

An Obsession with Natural History and Victorian Collecting Crazes

Spanning the majority of the 19th century, the Victorian era was marked by a rise in fashionable collecting hobbies. Natural history objects were among the items that fascinated the public, causing them to collect with feverish interest.

Table of contents

Ferns and shells were among the items that tantalized the general public and caused them to devote much of their newly found leisure time to collecting, examining, studying, sketching, and displaying these specimens. Armed with a basket and a pair of wellies, zealous collectors set off to the damp woodlands to acquire ferns or wade through the shorelines in search of shells and seaweed. This article will survey the historical instances of Pteridomania or “fern fever” and Conchylomania or “shell fever” in Victorian England.

Pteridomania or Fern Fever

In the late 1820s, Victorians were struck by a severe case of “fern fever” that manifested as an obsession with the primordial plant. What began as a marketing ploy, soon turned into a mania that swept through the classes turning hobbyists into amateur botanists.

The widespread fuss about ferns all began with the invention of the Wardian case by British explorer and surgeon Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward. The Wardian case was a glass hothouse that allowed plants to thrive outside their native environment. To promote his invention, Ward “spread the rumor that fern collecting showed intelligence and improved both virility and mental health” (2016 Nikolaidou). Bolstered by this favorable testament, fern collecting swiftly skyrocketed.

Fern collecting became an activity that allowed participants to elevate their social standing and demonstrate their mental capacity by partaking in the fashionable trend. Similarly, women were encouraged to participate as it was deemed an edifying, wholesale, and moral activity. In his 1855 book Glaucus, Charles Kingsley describes the effects of fern fever on young women:

Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing ‘Pteridomania’ … and wrangling over unpronounceable names of species (which seem different in each new Fern-book that they buy) … and yet you cannot deny that they find enjoyment in it, and are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip, crochet and Berlin-wool.

Wardian cases allowed plants to grow outside their native environment.

Wardian Case, England, 1870.

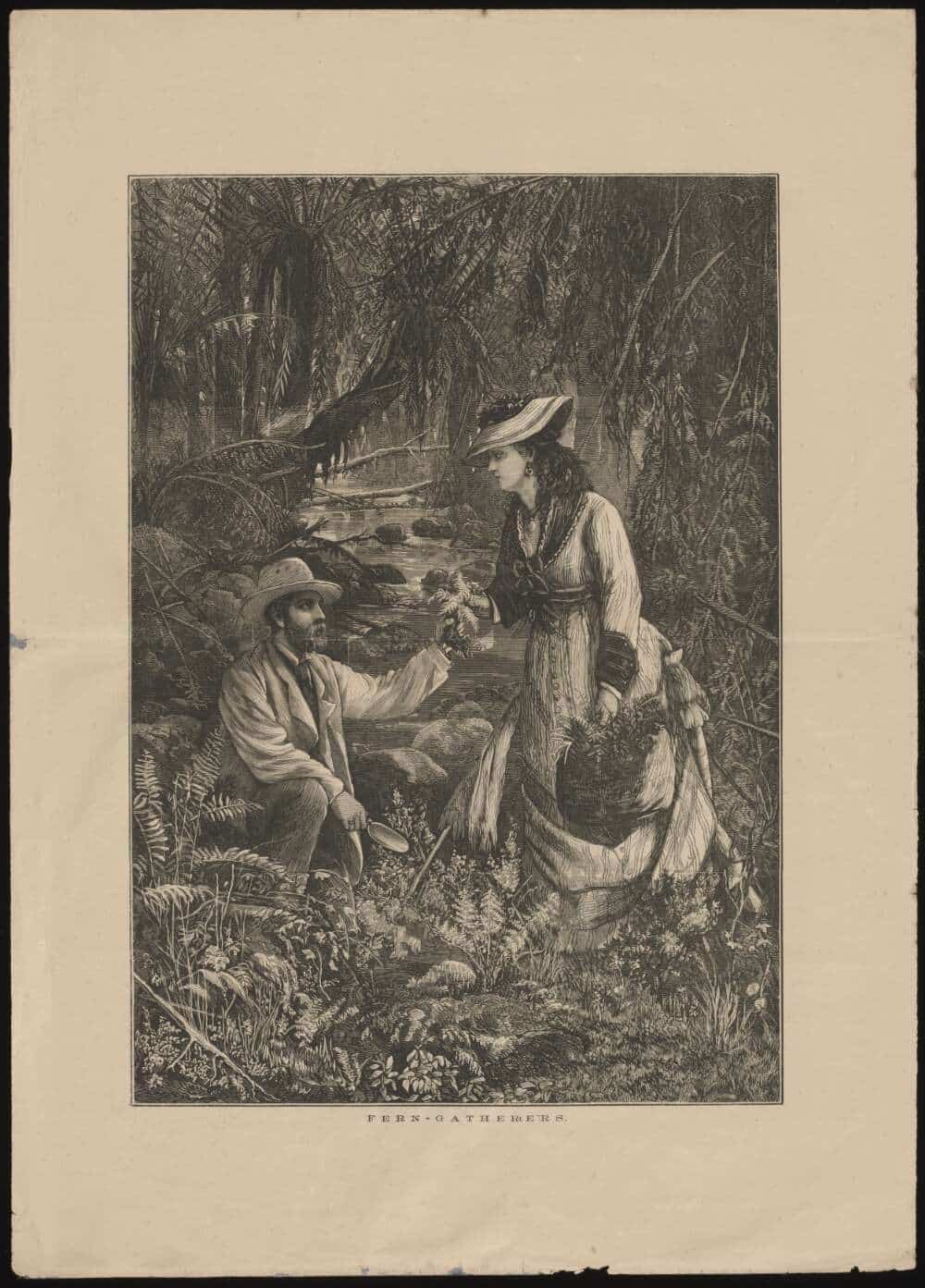

Fern collecting was an activity that young women were permitted to do unchaperoned.

A 19th-century depiction of fern gatherers. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Interestingly, fern collecting was an activity that young women were permitted to do unchaperoned which sometimes led to overnight expeditions with friends among the fronds. The prevailing idea was that examining nature would bring the pupil closer to god through the study of his creations. Therefore, it was deemed a permissible and moral hobby.

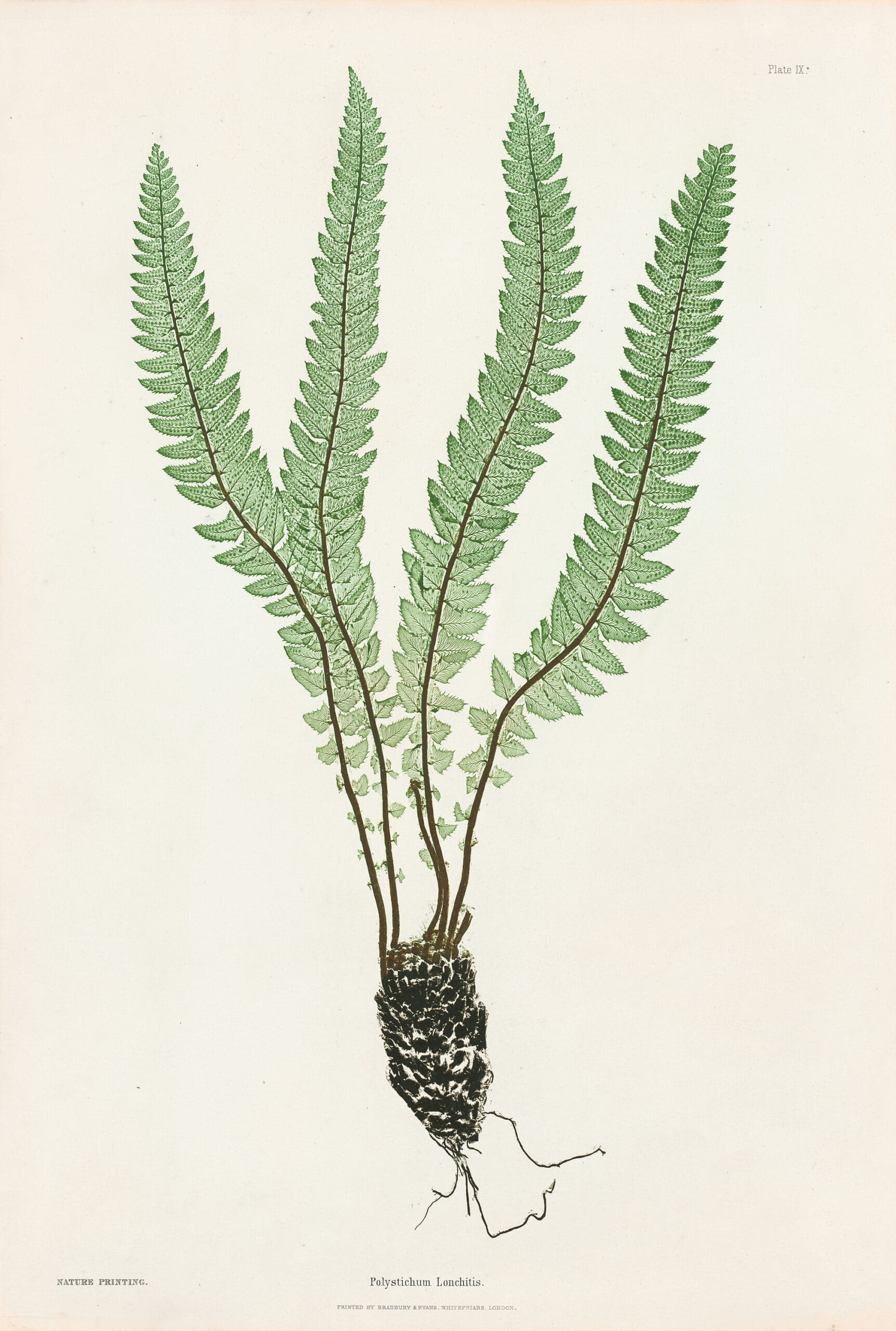

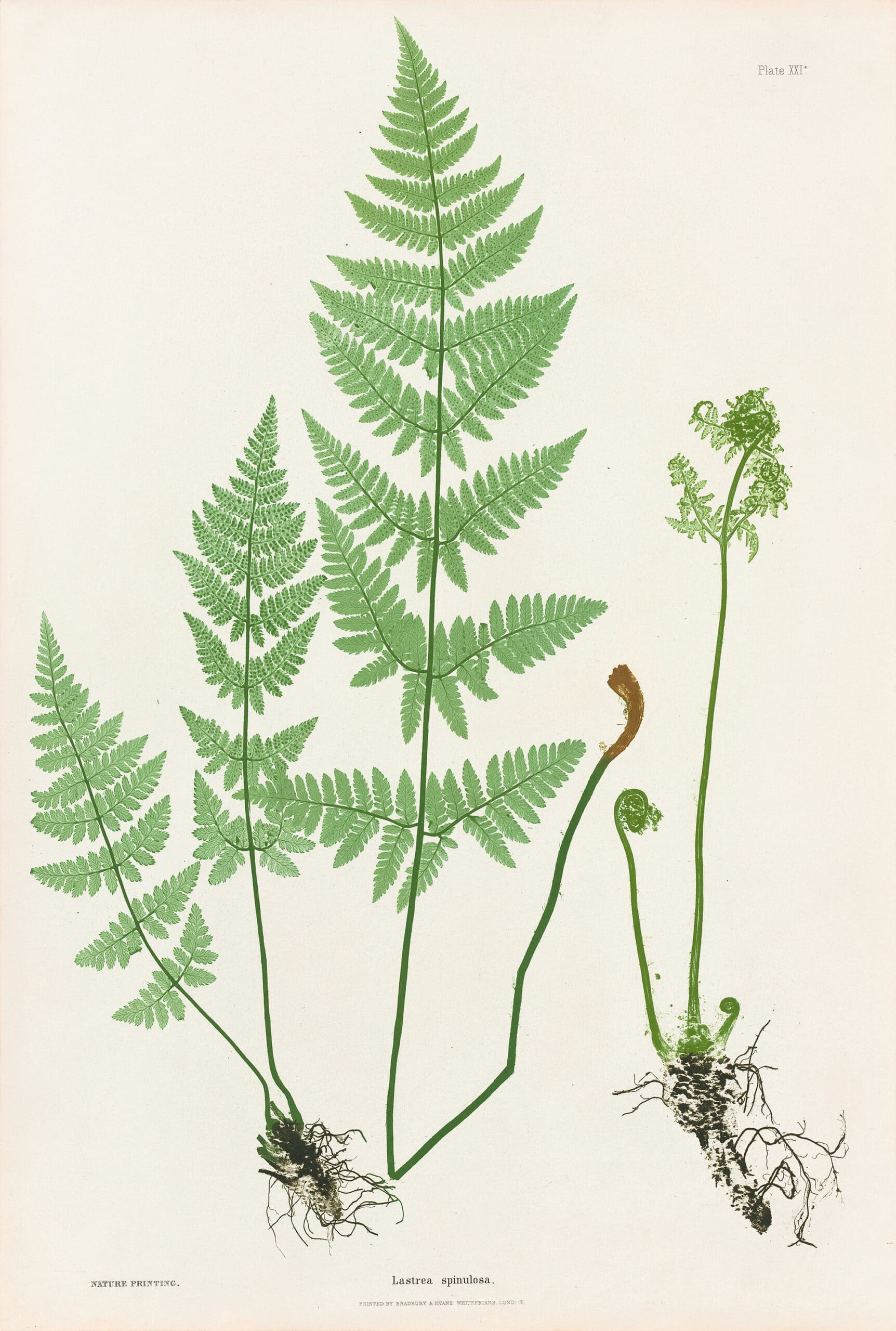

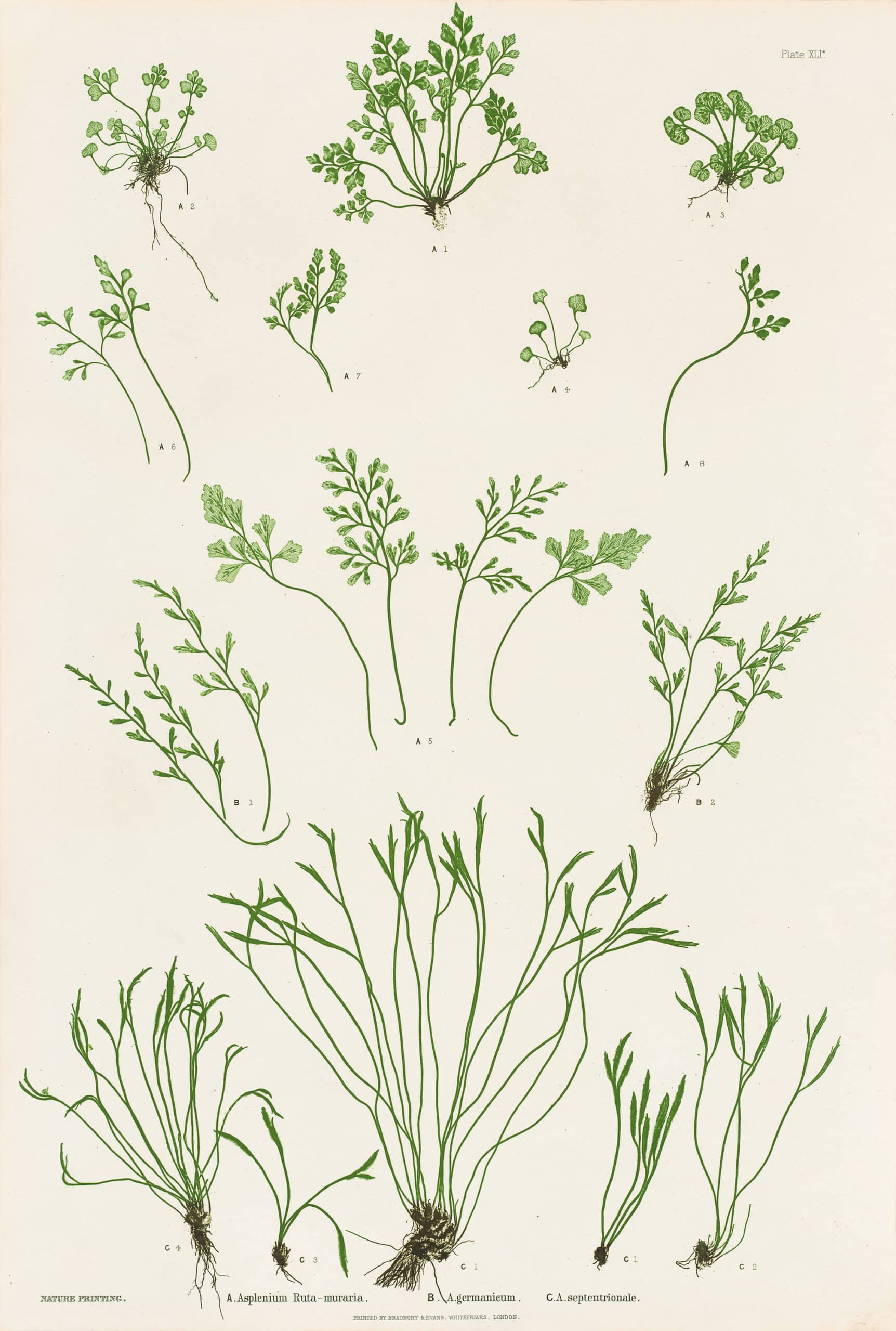

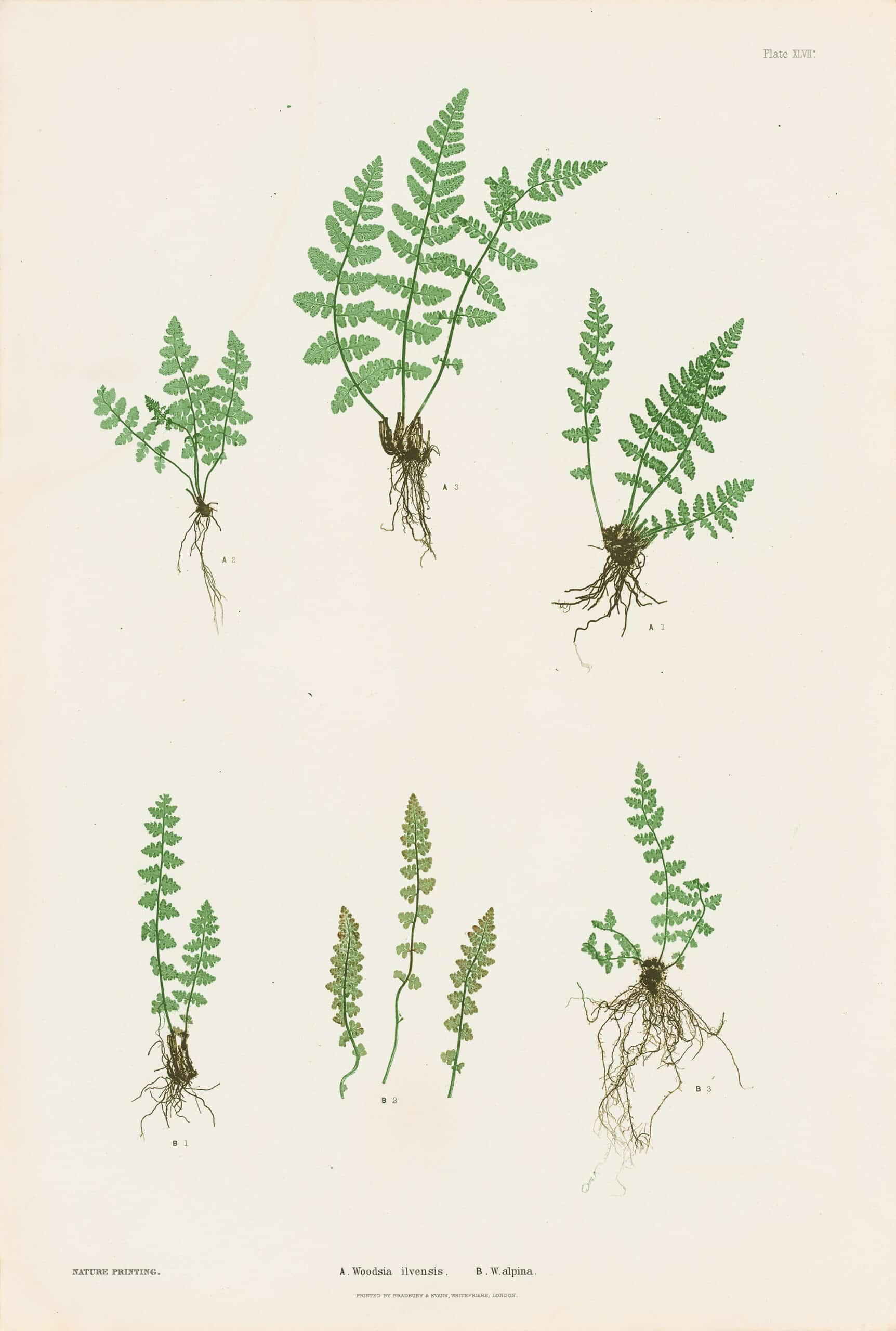

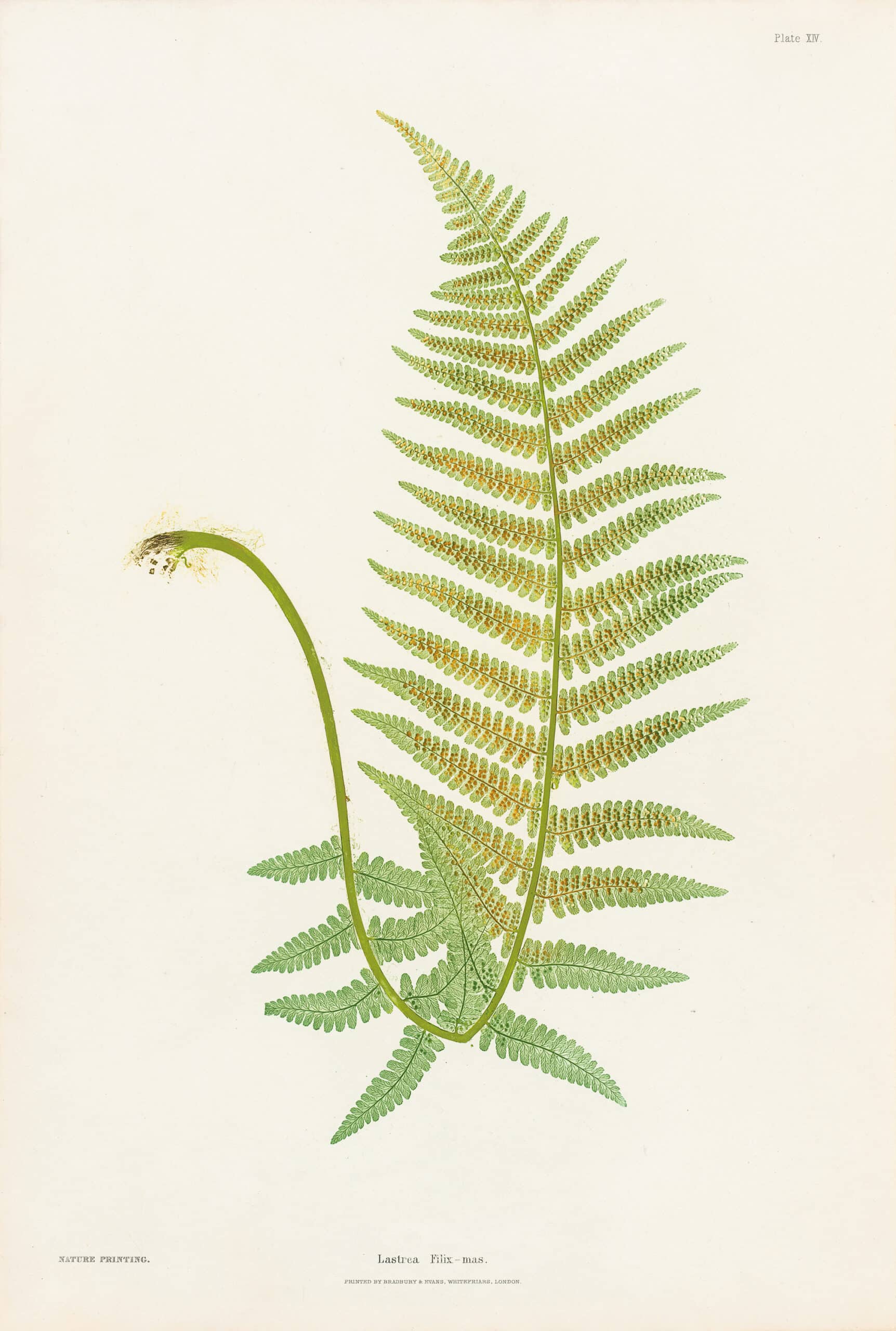

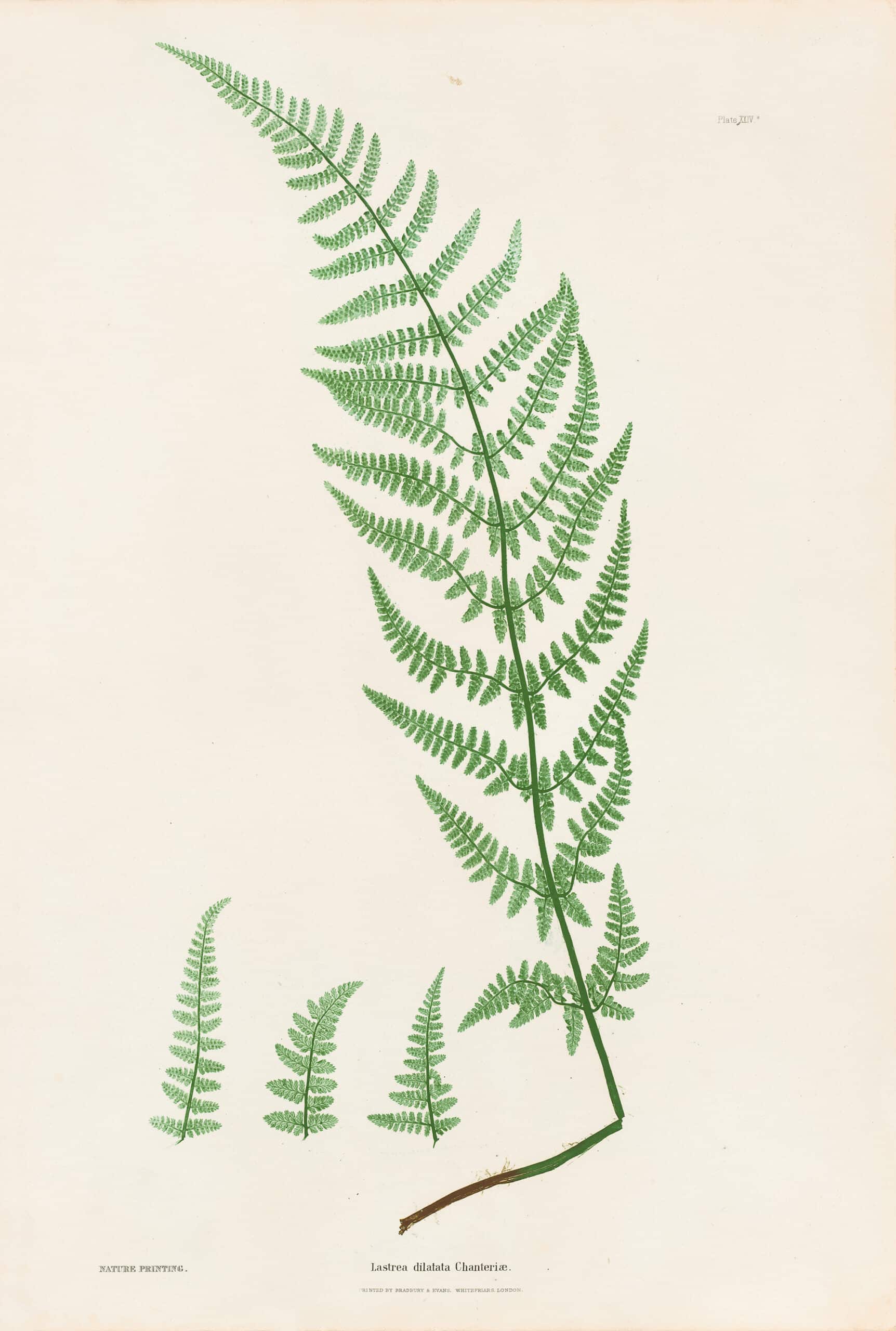

Thomas Moore’s illustrated publication The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland was released in response to the growing interest in ferns. He developed a precise method of nature-printing that involved pressing the plant into a lead plate which was then electroplated and used to print the plant imagery. The exactitude of his images made his monograph a popular guidebook for fern hunters.

Once the forests of Great Britain had been exhausted, new ferns were imported to sate the appetite of the frenzied Victorians. Unfortunately, the multidecade exuberance of their activities caused several species to near extinction.

Thomas Moore Fern Nature PrintsView Gallery

Conchylomania or Shell Fever

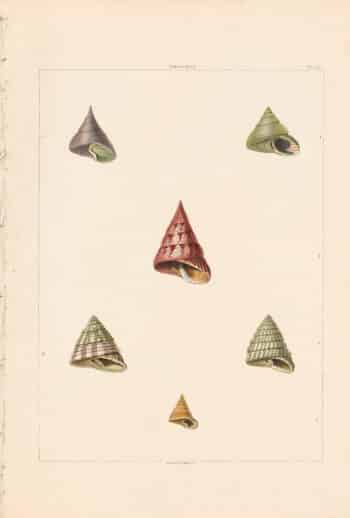

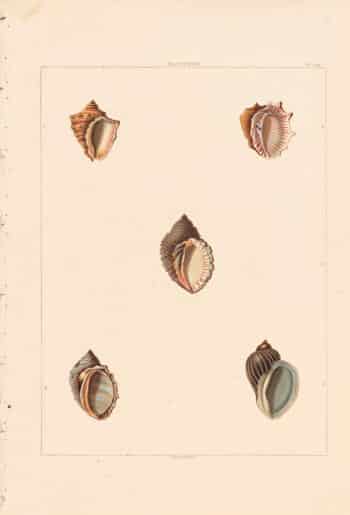

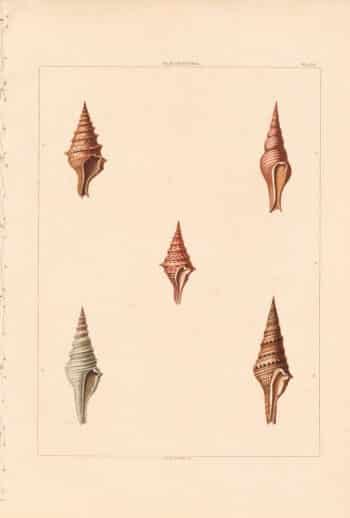

Another collecting craze that wracked Victorian hobbyists was Conchylomania or “shell fever.” Tied to expeditions of discovery and increased trade networks, shell collecting gained traction in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Dutch East India Company played a significant role in introducing exotic shell species to the European market. The history of shell collecting from this era is rife with stories of pricey specimens and counterfeit shells made of rice flour.

Wealthy collectors bought exotic shells imported by the Dutch East India Company from Indonesia while working-class collectors satisfied themselves with local varieties of shells found on British shores.

Jacques Linard, Still-Life of Shells and Coral on a Table Top, c. 1640

By the 19th century, the hobby experienced a revival among the Victorians on both sides of the Atlantic. Requiring little equipment to collect or store the shells, this pastime found popularity among men and women of all classes. While fern collecting might require dedicated cultivation or a Wardian case to produce a stable environment for the plant to thrive, shell collecting needs no such accessories. Wealthy collectors bought exotic shells imported by the Dutch East India Company from Indonesia while working-class collectors satisfied themselves with local varieties of shells found on British shores.

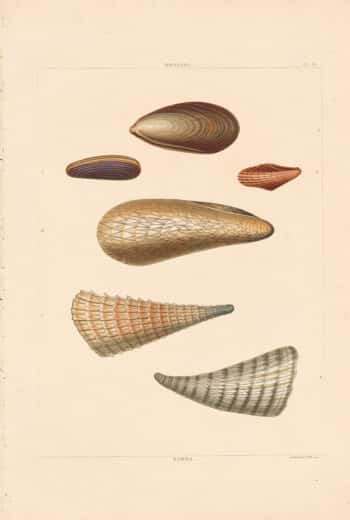

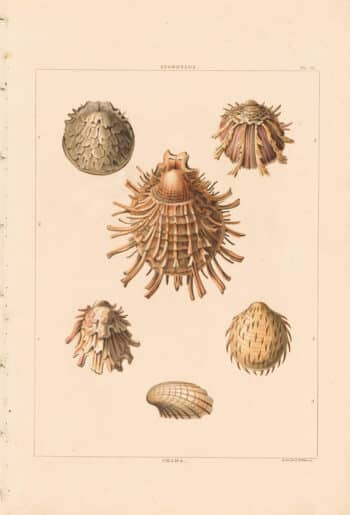

George Perry Shell EngravingsView Gallery

The widespread enthusiasm for shells is reflected in George Perry’s publication of Conchology, or, the Natural History of Shells, which was the first color encyclopedia of mollusks. Published in 1811, the folio begins with a glorification of the study of shells:

The study of Shells, or testaceous animals, is a branch of natural history which, although not greatly useful to the mechanical arts, or the human economy, is, nevertheless, by the beauty of the subjects it comprises, most admirably adapted to recreate the senses, to improve the taste or invention of the Artist, and, finally and insensibly, to lead to the contemplation of the great excellence and wisdom of the Divinity in their formation.

Promising to elevate the reader’s aesthetic sensibilities, inventiveness, and understanding of the divine, Perry’s introduction to Conchology relays the popular idea of nature as a conduit for personal and moral improvement. With this positive perception of the activity, it is not hard to imagine why individuals would be willing to spend significant amounts of time and money on shell collecting.

Shell collections were often stored in compartmentalized drawers.

Shells collected by Joseph Bank during the HMS Endeavour expedition 1768–71. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Many shell collections were often stored in drawers, displayed in cabinets among other natural specimens, or featured in one’s private library alongside accompanying literature like Perry’s Conchology. At the same time, a unique craft form – spearheaded by women – developed out of the cultural obsession with shells. Using shells as their primary medium, these women crafted extravagant bouquets, decorative displays, and sculptural assemblages from their mollusk findings. Inspired by their handiwork, a cottage industry of “sailors valentines” developed in which sailors returning from overseas voyages would purchase and gift these intricately designed shell objects to their loved ones.

Some women crafted extravagant displays out of shells.

19th-century shell bouquet

Many of the shells and other natural history specimens compiled during the Victorian era substantiate the basis of museum collections today. Moreover, many of these collections served as source material for scientific study and artistic folios like Thomas Moore’s The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland and George Perry’s Conchology.