Hudson River School

The Hudson River School Painters

Recognized as the first distinctively American art movement, the Hudson River School comprised a group of landscape painters who gained prominence during the 19th century for their monumental depictions of the American wilderness.

Table of contents

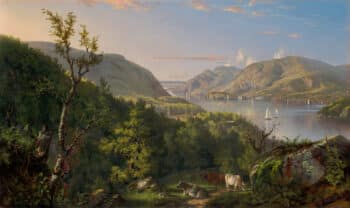

With New York and the Hudson River valley as the epicenter of this budding artistic movement, the sobriquet “Hudson River School” was used to identify the group of landscape artists who consciously sought to create a distinctively American style of art by drawing from the landscape itself. While the subject matter and stylistic approach of the individual artists vary, the Hudson River School painters are united by their mission to create a self-consciously “American” landscape vision based on the exploration of the natural world as a resource for spiritual renewal and expression of cultural and national identity.

Historical Backdrop

After having gained independence from Britain in 1776, the United States of America sought to slough off the ties of British art and culture by developing a unique artistic voice and distinctively American identity. As a movement grounded in the veneration of the land itself, the Hudson River School offered an alternative to European history and culture. Additionally, landscape painting proved an effective tool for mediating one’s connection to nature in an era of increased industrialization. Moreover, the Hudson River School paintings visually record American expansion in pursuit of resources and progress. Thus the nubile landscape was used to symbolize American identity, potential, and prosperity.

Thomas Cole & The Founding of the Hudson River School

Perhaps ironically, the roots of the Hudson River School movement can be traced to the work of English emigrant Thomas Cole. Characterized by dramatic landscapes and painterly techniques, Cole’s style set the precedent for subsequent American landscape painters including two of the Hudson River School’s most notable artists Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt. With the developments in locomotion and the establishment of railroads in and around New York, these men were able to access and paint scenery that was previously inaccessible to most Americans.

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow

Thomas Cole, 1836

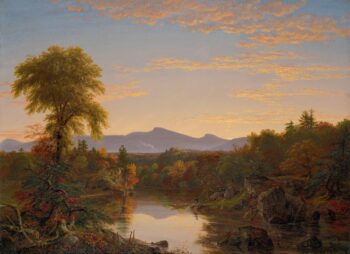

When viewing Cole’s artwork, one is struck by the incredible majesty of nature and the relative insignificance of man. Take for instance View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, which measures an immersive 51 1/2 x 76 inches and rivals the actual vista in beauty and power. In the foreground, a time-worn tree raises its weary, splintered fingers in a tired salute. In stark contrast to the ominous storm brewing to the left of the composition, the right side features an idyllic valley lining the oxbow lake. Orderly fields, chimney smoke, and plowed plots indicate human presence and a pastoral way of life in vivid juxtaposition to the wild and unruly scenery to the left. Meanwhile, seated front and center at the cliff precipice, the artist features himself painting the scene below.

In this composition, Cole emphasizes the power and unpredictability of nature as a means of prompting the viewer to consider the fragility of life and man’s relationship to the natural world. In doing so, Cole conjures what European artists and poets of the Romantic movement called the Sublime, which can be described as the sense of awe and terror that is awakened when one is faced with the grandeur of nature. In this way, Cole creates a dialogue with the concerns of the European art world while elevating the American landscape. Cole asserts that “The painter of American scenery has indeed privileges superior to any other; all nature here is new to Art” (Journal entry, 1835). The novelty of the undocumented American landscape served to carve out a space for the United States on the global art stage.

Going West – American Expansionism and Manifest Destiny

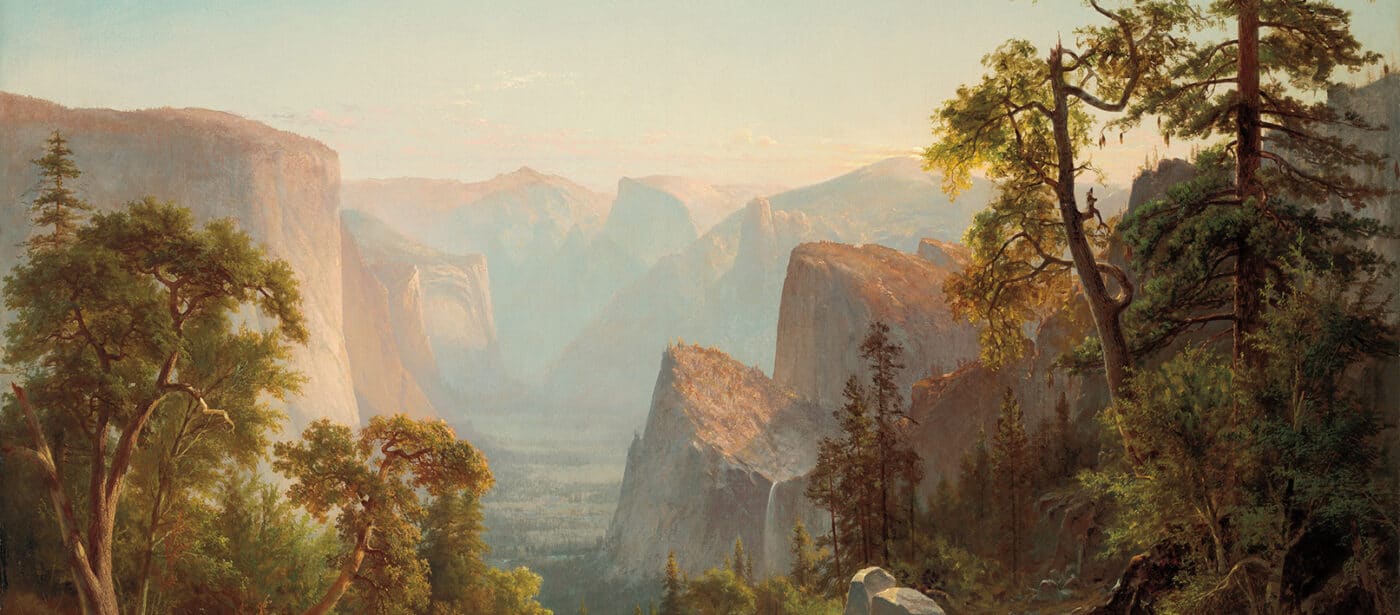

Much like Cole’s magnificent canvas, Albert Bierstadt’s Donner Lake from the Summit elicits a similar sense of rapture. Measuring 6 1/8 × 10 ft. 3/16 in, this immense painting envelopes the viewers in its hazy embrace and momentarily transports them to the high vista. The scene depicts the weathered trees, effervescent lake, and craggy mountains of the Sierra Nevada in California. Tucked away to the right side of the painting, a train passes by on a newly constructed railroad.

While the overwhelming focus of the painting is the dynamism of the landscape, the inclusion of the railroad implicates several notable historical and political events of the mid-19th century. During this time, the notion of manifest destiny, or the idea that European settlers were preordained by God to occupy all of North America, was promulgated to excuse the displacement of native populations in pursuit of more land and resources in the West. The building of the Transcontinental Railroad solidified America’s access to the Pacific Coast and solidified California’s admission to the Union as a state. Thus Bierstadt’s landscape acts as a vehicle for national expression by glorifying American occupation of the West.

Looking Beyond North America

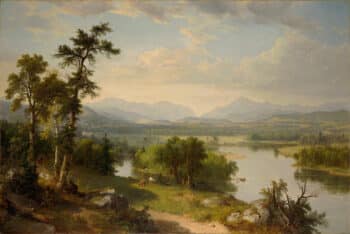

However, the Hudson River School painters did not limit themselves to depictions of North America but instead took their explorations beyond the continent’s borders. Frederic Church, a student of Cole, was inspired by the travel accounts of German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and took it upon himself to experience and depict the Andean region of South America.

His painting Cayambe captures the dynamic landscape and rich ecology of Ecuador. The foreground of the painting heaves with the weight of the dense, tropical foliage that dominates the landscape, claiming the rocky cliffs and crumbling architectural features of bygone eras. Beyond the foliate screen, a glistening lake reflects the icy image of Mount Cayambe. This snow-capped volcano pierces through the dusky clouds and creates a stark contrast to the tropical jungle below. One is instilled with a sense of awe and wonder at the grandeur of the landscape and the dominance of natural forces over manmade elements. Thus Church emphasizes the finite nature of man’s existence and the inevitable rise and collapse of civilizations.

Without a common history or shared culture to unite them, early American artists looked to the land itself as a source of unification and expression. Armed with a sense of naive wonder and driving curiosity, the Hudson River School painters set out to represent the American landscape so that it, in turn, would represent the spirit of the American people in art.

References

Avery, Kevin J., Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, John K. Howat, Doreen Bolger Burke, and Catherine Hoover Voorsanger. American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

Avery, Kevin J. “The Hudson River School.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hurs/hd_hurs.htm (October 2004)

Howat, John K. “The Hudson River School.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 30, no. 6 (1972): 272–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/3258969.