Birds and Animal Art, Information

The Alchemy of Nature – Using Gold in Natural History Art

Gold, like other minerals and organic compounds, has been used as a decorative and symbolic feature in artwork for centuries.

Prized for its visual, allegorical, material, and monetary appeal, gold has been used for millennia in the arts to connote prestige and to conjure feelings of abundance and otherworldliness. The ore can be found adorning Egyptian papyri, enhancing the marginalia of Medieval illuminated manuscripts, and lending a sacred, otherworldly atmosphere to Buddhist paintings and Byzantine icons. While found less frequently in natural history art, gold nonetheless makes an appearance in a number of depictions of plants, animals, and fish around the 18th and 19th centuries.

Medieval illuminated manuscripts were often embellished with gold leaf.

“Pastoral D” from Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana Pal. lat. 1632 Vergilius Maro, Publius, fol. 40v.

Gold Leaf in Hand-colored Lithographs

In contrast to gold’s use in other genres of art such as religious paintings, portraits, and historic or allegorical scenes, the ore’s use in natural history art was typically not intended to elicit notions of power or feelings of the divine. Rather, its lustrous qualities were deployed to heighten the jewel-like appearance of an iridescent bird’s feather or to enhance the reflective qualities of a scaly fish.

Gold leaf was used to accentuate the crest and wings of this magnificent bird.

Daniel Giraud Elliot Pl. 19, Great Sickle-bill Bird of Paradise (Uncolored)

View Artwork

Translucent watercolor pigments are applied to the image, allowing the reflective gold to shine through and enhance the vivacity of the bird.

Daniel Giraud Elliot Pl. 19, Great Sickle-bill Bird of Paradise (Colored)

Daniel Giraud Elliot’s Birds of Paradise

Take for instance this magnificent black and white lithograph depicting the Great Sickle-bill Bird of Paradise by 19th-century artist Daniel Giraud Elliot. Perched on a slim branch in the temperate environment of Papua New Guinea, the ostentatious bird ruffles its gold-finished wings in an attempt to impress a nearby female. In addition to the gold bands ornamenting the bird’s wings, a thin overlay of gold leaf adorns his crown, as though attesting to the opulent and unencumbered lifestyle of the bird of paradise. This lithograph is a unique, uncolored example of Elliot’s Great Sickle-bill Bird of Paradise (left) which, in addition to the gold leaf overlay, was typically colored with watercolor and gouache as seen in the example on the right. After the color is applied, the gold leaf underlay is detectable as a subtle shimmer, enhancing the iridescent and life-like qualities of the bird.

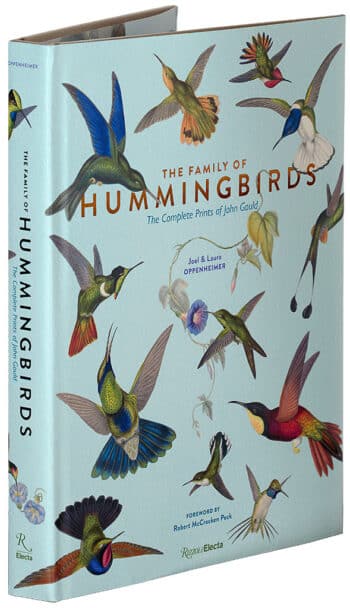

Gold leaf was used to capture the jewel-like qualities of the hummingbirds.

John Gould, Monograph of the Trochilidae or Family of Humming Birds (1849 -1861)

View HummingbirdsJohn Gould’s Hummingbirds

Predating Elliot’s Bird of Paradise is perhaps the most prominent and controversial instance of the use of gold leaf in natural history art by 19th-century artist and publisher John Gould. For his masterpiece Monograph of the Trochilidae or Family of Humming Birds (1849 -1861), Gould developed a technique for capturing the gem-like qualities of the hummingbirds “by employing gold leaf as an underlayment in the coloring process” (Oppenheimer 2011, 30). In this process, which Gould patented and debuted at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, “a combination of transparent oil and varnish colors over pure leaf gold laid upon paper, prepared for the purpose” resulted in a sheen and luster that wondrously captured the glistening appearance of the hummingbird’s feathers (Oppenheimer 2011, 33).

However, Gould’s patenting of the gold-underlay technique was not without controversy. In 1919, the nephew of American artist William Baily, who had been experimenting with a similar gold leaf process at the same time as Gould, claimed that his uncle contributed to the development of Gould’s technique without proper acknowledgment. In fact, vast written correspondence between the two men indicates that Gould sought information from Baily about his method of reconciling the incompatibility of the gold leaf and watercolor paint. As Joel Oppenheimer explains in his book, The Family of Hummingbirds, “When water-soluble pigments are layered over a metallic element, there is an inherent incompatibility of materials” (Oppenheimer 2018, 30). However, though Baily’s experimentation fueled Gould’s pursuit of the same outcome, both artists arrived at slightly different techniques for achieving similar results. While Baily’s method involved “combining a thin layer of gelatin with pigments ground in honey”, Gould’s method employed “lacquer or oil glazes” to enable the gold leaf to be painted over with watercolor (Oppenheimer 2011, 36 & 38).

Sheet of gold leaf

Photo credit: Barnabas Gold

Shell Gold in Natural History Art

Another method of applying gold to works on paper was to use metallic pigment rather than gold leaf. In this procedure, the gold is ground into a fine powder and mixed with a binder such as gum arabic or egg white. It can then be applied to the artwork with a brush or pen. Unlike gold leaf, powdered or “shell” gold was added to the artwork at the final stage after the printing and coloring were complete.

Pigment made of ground or “shell” gold, named in reference to its typical storage container, is made of tiny particles of gold suspended in gum arabic or egg yolk.

Photo credit: Anita Chowdry

Audebert & Vieillot’s Exotic Birds

The use of shell gold can be seen in Jean Baptiste Audebert and Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot’s magnificent folio Oiseaux dore´s, ou a re´flets me´talliques (1800-1802). Containing 190 vivid depictions of exotic birds, the illustrated folio captured the brilliant plumage of birds of paradise, hummingbirds, jacamars, and other tropical birds all heightened with metallic pigment. While the gold leaf technique employed by Gould and Baily resulted in a smooth shimmering surface, the ground gold pigment used by Vieillot tends to appear more granular and less reflective (Jackson 2011, 56).

Bird of Paradise from Audebert and Vieillot’s Oiseaux dorés ou à reflets métalliques

Ground gold was used to embellish the brilliant bird of paradise.

Bloch’s Fish & Martyn’s Shells

In addition to enhancing the iridescent qualities of bird feathers, gold leaf and gold ground were used to highlight the prismatic qualities of fish scales. For example, Marcus Elleser Bloch’s Ichtyologie, ou, Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière des poissons (1785–1797) “became one of the most beautiful books about fishes owing to the hand-colouring which was heightened with silver and gold”(Jackson 2011, 57). Using metallic gold and silver pigments, Bloch captured the shimmering sheen of the fish. Unlike Gould’s process of applying gold leaf to paper that was then printed and painted over, Bloch used a metallic pigment that was applied to the print as a final touch after the coloring process. Similarly, Thomas Martyn used this same technique in his monograph The Universal Conchologist (1784–1787) which examined numerous different types of shells in vivid color.

Marcus Elleser Bloch captured the shimmering quality of the fish’s scales with gold pigment

Artwork from Ichtyologie, ou, Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière des poissons (1785–1797)

Thomas Martyn used gold pigment to enrich his depictions of shells

Artwork from The Universal Conchologist (1784-1787)

The infrequent but enchanting use of gold leaf and shell gold in natural history art enables the depicted species to come alive, glinting and glistening on the page. Likewise, a greater sense of dynamism and depth is achieved through the optical properties of gold. Moreover, the application of gold to these compositions lends a preciousness to the artwork, enhancing both its visual and material qualities.

References

Jackson, Christine E.. 2011. The Materials and Methods of Hand-colouring Zoological Illustrations. Archives of Natural history 38.1: 53–64.

Oppenheimer, Joel & Laura. 2018. The Family of Hummingbirds: The Complete Prints of John Gould. New York: Rizzoli Electa.

Joel & Laura Oppenheimer | Published by Rizzoli

A Monograph of the Birds of Paradise - Antique Originals

Original hand-colored lithograph | circa 1872 | 23 ½ x 18 ½ inches

A Monograph of the Birds of Paradise - Antique Originals

Elliot Pl. 19, Great Sickle-bill Bird of Paradise (Uncolored)

Original Lithograph | circa 1873 | 23 ½ x 18 ½ inches

A Monograph of the Birds of Paradise - Antique Originals

Original Lithograph | circa 1873 | 23 ½ x 18 ½ inches

Family of Hummingbirds - Oppenheimer Editions

Gould Hummingbirds Pl. 55A, Grey Stripetail | By Oppenheimer Editions

Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print | circa 2013 | Limited edition of 200 | 21 7/8 x 15 inches

Family of Hummingbirds - Oppenheimer Editions

Gould Hummingbirds Pl. 56A, Copper-tailed Amazili | By Oppenheimer Editions

Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print | circa 2013 | Limited edition of 200 | 21 7/8 x 15 inches

Scarves

Made in the U. S. A. from the finest quality 100-percent silk twill.