Audubon Prints, Birds and Animal Art, Information

Exploring Early Methods of Specimen Collection in Natural History Art

Have you ever wondered where the reference material for wildlife art came from before the ubiquity of photography? Was the artist depicting a living creature or a taxidermied specimen? This article explores several methods of specimen acquisition used by early natural history artists.

Table of contents

Before the advent of color photography and the prevalence of images via the internet, wildlife was typically viewed in the following ways: alive in nature, as stuffed specimens in private or museum collections, as inhabitants of zoos and menageries, or as rendered by artists. Viewing birds and animals in the wild had its drawbacks as it was often extremely labor-intensive, costly, and dangerous requiring the artist to venture to the native locale of the desired species. However, this method of specimen collection had the immeasurable benefit of allowing the artist to understand how the particular bird or animal interacted with its environment.

Another method of viewing live and often exotic species was through zoos or menageries where the imported species were housed for visual entertainment, zoological study, or as attestations of the owner’s wealth and erudition. However, as captive creatures extracted from their native environments, the animals were observed out of their original context and complex ecology. Thus this method of viewing offered a limited understanding of the bird or animal.

Menageries were one way of viewing exotic birds and animals

‘Royal Menagerie, Exeter Change, Strand, London’, c. 1820.

However, it was often the case that living specimens were hard to come by which forced numerous artists to work from stuffed specimens and skins, an abundance of which were on display in public and private collections. Each method of observation had its unique challenges and benefits, and often a combination of the different viewing approaches was used by early natural history artists to create their folios.

The Intrepid Explorer

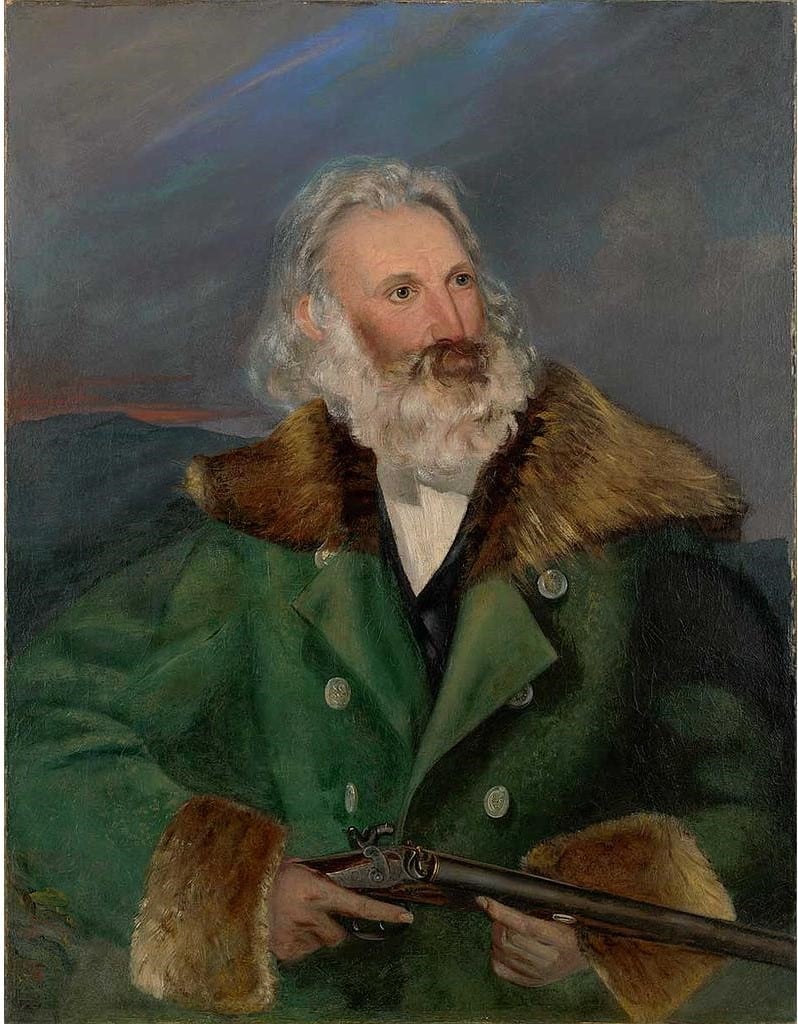

Rivaling the notability of his seminal Birds of America folio was the image of John James Audubon himself as a rugged backwoods explorer and naturalist. Audubon famously spent decades traipsing through the American wilderness in search of birds to draw and paint for his comprehensive publication on North American avian life. Aided by his shotgun and an occasional assistant, Audubon acquired the majority of his bird specimens in the wild after observing them in their natural habitat and taking notes on their unique calls, movements, and idiosyncrasies.

Once the specimen was acquired (shot), Audubon used a system of pins and wires to affix the bird to a board mount in a lifelike position. He then sketched and painted the specimen, calling upon his observations of the living bird in nature and the strategically positioned specimen in front of him. Thus Audubon was able to capture the life-like qualities of the bird by both observing it in nature and up close as a specimen.

Portrait of John James Audubon by his son John Woodhouse Audubon

Audubon’s Watercolors – The American Museum of Natural History Edition

view artAudubon’s meticulously kept journals provide insight into his working process and relay the harrowing tales of his wilderness exploration. During one memorable escapade, Audubon found himself stuck in quicksand while pursuing a great horned owl. He recalls:

“I once nearly lost my life by going towards [a great horned owl] that I had shot on a willow-bar, for, while running up to the spot, I suddenly found myself sunk in quicksand up to my arm-pits, and in this condition must have remained to perish, had not my boatmen come up and extricated me, by forming a bridge of their oars and some driftwood, during which operation I had to remain perfectly quiet, as any struggle would soon have caused me to sink overhead.”

Audubon’s journals paint an image of the artist as a lone explorer immersed in nature and motivated by an unquenchable desire to discover and create. By viewing the birds in nature and taking specimens as primary reference materials for his art, Audubon was able to depict the species with incredible detail, accurate positioning, and immersed in its native environment.

While Audubon sourced the majority of the specimens himself, there were occasions where he enlisted the aid of associates to acquire the birds or was limited to referencing taxidermied specimens as was the case with the now extinct Great Auk. On a few occasions, Audubon kept live birds to observe them as was the case with the American kestrel and wild turkey, which inevitably informed his sketches and watercolors of the species.

Audubon was forced to work from a taxidermied specimen as the Great Auk neared extinction and very few birds were left to be found in the wild.

Taxidermied Great Auk from the early 19th century

The Institutionally Sponsored Expedition

In contrast to Audubon’s self-funded explorations, Daniel Giraud Elliot and Louis Agassiz Fuertes often participated in institutionally sponsored zoological expeditions to inspire their art.

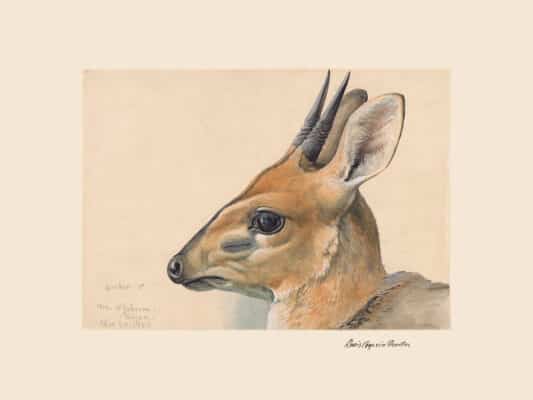

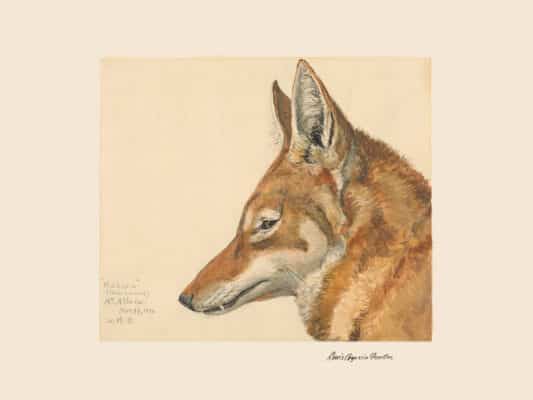

While serving as curator of the Field Museum in Chicago, Elliot led The Field Columbian Museum East Africa Expedition to Somalia in 1896. Accompanied by the museum’s Chief Taxidermist Carl Ethan Akeley and former British Museum taxidermist Edward Dodson, Elliot and his companions studied and collected thousands of specimens. Their primary mission was to source African bird and mammal specimens for the natural history museum’s collection. In addition to fulfilling his duty as a zoological curator, Elliot found abundant inspiration for his art on such expeditions.

Institutional expeditions were another way for artists to access exotic wildlife

Photo of Elliot in Berbera, Somalia during the Field Columbian Museum East African Expedition of 1896

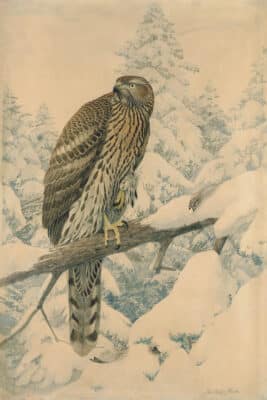

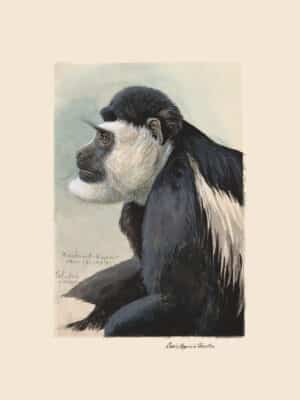

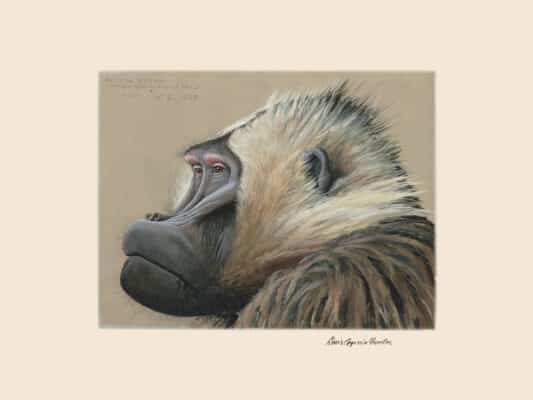

Similarly, in 1926 artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes accompanied by Field Museum curator Wilfred Osgood, and big-game hunter James E. Baum set out to Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia) on a sponsored expedition funded by the Field Museum and Chicago Daily News. While in Abyssinia they aimed to study wildlife, hunt game, and acquire specimens for the Field Museum collection.

Fuertes’s Abyssinian watercolors focus on aspects of the bird that would not be preserved once the specimen was killed and taxidermied.

Fuertes Pl. 26, African Lammergeyer

view art

Fuertes posing a Lammergeyer for sketching

The Field Museum, CSZ55287, Photographer Alfred M. Bailey.

Fuertes’ watercolors from this expedition are glorious in their lifelike quality. His confident brushstrokes familiarize themselves with the shape and contour of the birds and animals. Working from live creatures, Fuertes focuses on the eyes, feet, and posture of the animal – aspects that would be difficult to preserve in a taxidermied specimen. Fuertes had every intention of later revisiting his watercolor sketches to turn them into more formal paintings but only a few weeks after returning home from the expedition, he was killed by a train while driving his car. His paintings, which were with him at the time, survived the collision and were later sold to the Field Museum where they are housed today.

In addition to their museum-sponsored expeditions, Elliot and Fuertes undertook extensive independent travels to study and depict wildlife. Their methodology prioritized viewing the live species in nature and collecting specimens for artistic reference.

The Stay-at-home Naturalist

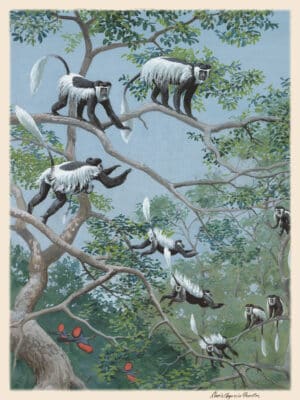

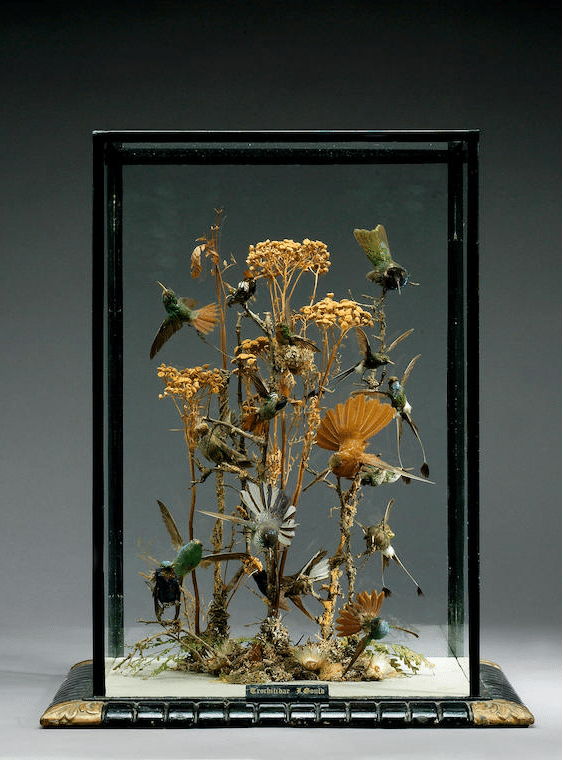

When no institutional funds were available and resources for travel were limited, artists often turned to local menageries, private collections, and institutional holdings for inspiration. Some artists even assembled their own extensive collections by purchasing imported specimens as is the case with John Gould’s hummingbirds. While Gould did engage in extensive fieldwork for several of his folios, his monumental Family of Hummingbirds folio was entirely illustrated from hummingbird skins and stuffed specimens rather than live birds.

Gould’s illustrations for the Family of Hummingbirds folio were drawn from taxidermied specimens imported from the Americas.

Photo of the glass cases displaying Gould’s collection of hummingbird specimens

John Gould’s display case of hummingbirds circa 1850

Without the financial means of traveling to the tropics, Lear turned to the local Zoological Gardens for inspiration.

Lear Pl. 2, Red and Yellow Maccaw

view artIn a similar vein, Edward Lear created his Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots based on sketches of the parrots in the Zoological Gardens at Regents Park. At 18 years old, Lear did not have the finances to travel to the tropics and observe parrots in the wild. Rather, he made use of his access to the Zoological Gardens where he routinely sketched its occupants. Several years later, Lear was invited to stay at Knowsley Hall where he had access to the extensive private menagerie of Lord Stanley, the 13th Earl of Derby. Lear spent several very productive years at Knowsley Hall where he produced Gleanings from the Menagerie and Aviary at Knowsley Hall and many other illustrations for various natural history publications.

Lear’s approach to natural history was an effective way of preserving the life of the subject but often disallowed him from viewing the animal in its native habitat. Extradited from their context, the birds are shown against a scant background. Despite the lack of context, this method of natural history illustration mitigated the cost and danger of field expeditions and spared the life of the bird.

In conclusion, there were myriad ways in which natural history artists acquired the subject matter for their folios. Some endured solitary voyages through the wilderness while others embarked on organized expeditions or turned to local menageries and collections for inspiration.