Art Restoration, Information

The Language of Paper – Deciphering the Secrets of Antique Paper through Its Material Qualities

Though it is not uncommon to turn to paper in search of knowledge, we typically rely on the written or drawn contents of its surface rather than the substrate itself as a source of information. However, indications of a stock’s place of origin, method of manufacture, date of creation, and even memory of the particular craftsman’s hand are often woven into the characteristics of the sheet itself. This article will examine several notable material qualities of antique paper and the corresponding stories harbored there.

Table of Contents

Early Papermaking in Europe – Laid Paper

Early European papermaking methods relied on the use of a mould, typically constructed out of a tight web of wires supported by a rectangular wooden frame, in order to form a sheet of rag paper. To create a sheet of paper, the mould was first submerged into a vat of fibrous sludge, often macerated linen and cotton suspended in water, so that the mixture was evenly distributed throughout the mould. Once removed from the vat, the mould retained the fibrous material while the excess water drained away.

This lithograph depicts three men at work in a papermill: One dips the mould into a vat to collect rag pulp, another flips the mould to deposit the paper onto a felt surface, and the third dips the fully formed paper into gelatin to size it.

Papier, lithograph on paper, 1840 Germany

Next, a series of drying and compressing procedures were carried out to relieve the newly formed paper of moisture and to consolidate the fibers. When holding a sheet of laid paper up to the light, a fine pattern of vertical and horizontal lines becomes visible recalling the interlaced wires of the mould. Formed by the impression of the wire mould, these lines have a thinner constitution than the rest of the sheet and thus transmit more light when illuminated from behind. The bold vertical lines, called chain lines, are intersected by a series of more delicate, horizontal “laid” lines. Thus, this type of paper is called laid paper and was the dominant substrate used to produce written, printed, and drawn material from the 12th to mid-18th centuries.

The laid paper mould has a strong gridwork of horizontal and vertical lines that are retained in the paper produced.

Two-sheet laid papermaking mould with watermark designs. Wookey Hole, England, ca. 1900. Gift of Calvin P. Otto in the Rare Book School collection.

However, laid paper was not without its challenges as the subtle textural difference of the paper’s surface made it difficult to work in delicate mediums such as watercolor and ink, which had the tendency to pool in the furrows and might pool in the could be interrupted by the textured topography of the laid paper.

The Introduction of Wove Paper in the 18th Century

By the mid-18th century, a new method of papermaking was introduced which resulted in a smoother, more homogenous paper stock called wove paper. Developed in England by James Whatman around 1755, wove paper was produced by using a fine woven mesh mould with less clearly defined constituents than the mould used for laid paper. This new method of paper production created stock with a more uniform texture and appearance, causing wove paper to surpass laid paper by the 19th century. Recognizing the visual and structural differences between laid and wove paper can be an important aspect of dating documents and works on paper.

The mould used to produce wove paper has a fine mesh screen that creates a more uniform texture and appearance than laid paper.

Wove mold with deckle and watermark designs, Fabriano, Italy – Robert C. Williams Paper Museum

Laid paper reveals a grid-like pattern when illuminated from behind.

Wove paper has a smoother, more uniform appearance than laid paper.

Before the 19th century, most paper made in Europe and America was made from rag rather than wood pulp.

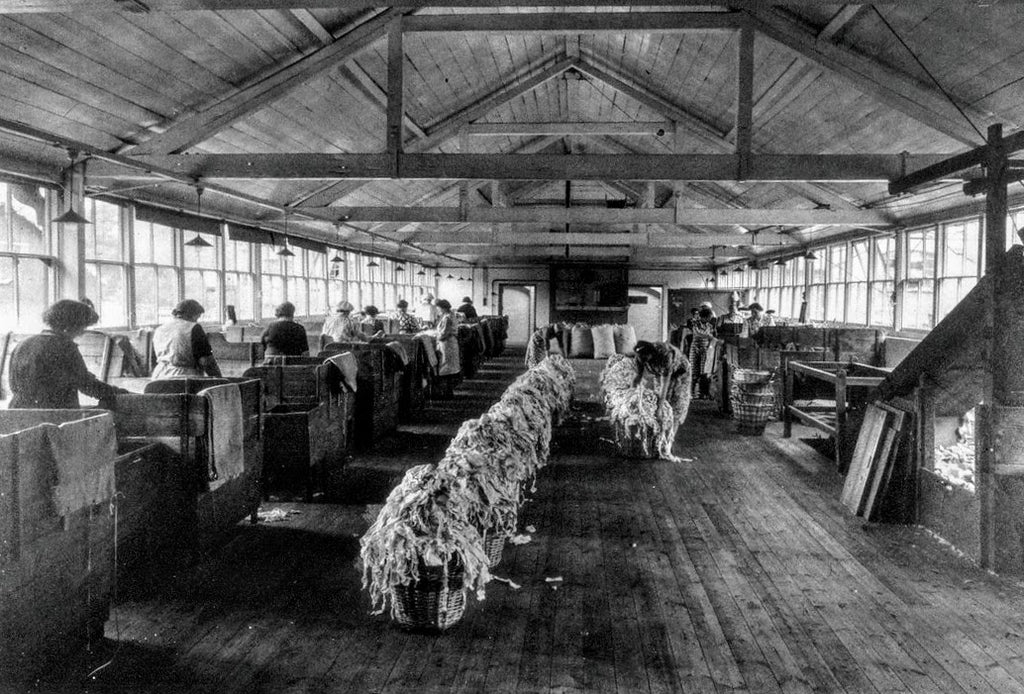

Women at Whatman’s papermill prepare rags for the Hollander beaters, which transform the scrap into a fine pulp for papermaking. Photo from Vintage Paper Co.

Materials: Rag vs. Wood Pulp

As previously mentioned, paper produced in Europe between the 12th – 18th centuries was typically made from natural, non-wood fibers including cotton and linen. However, by the mid-19th century, wood pulp gradually replaced rag pulp as the primary material of paper. This transition occurred because of the increasing cost and scarcity of rags in comparison to the cheaper, readily available wood option. Moreover, the introduction of the sulfite wood pulp process in 1882 caused wood-based paper to be produced and used on a massive commercial scale. Interestingly, antique rag paper stocks tend to be more resilient than their modern wood-pulp counterparts which have a tendency to turn brown and brittle because of the high acid content of the wood fibers.

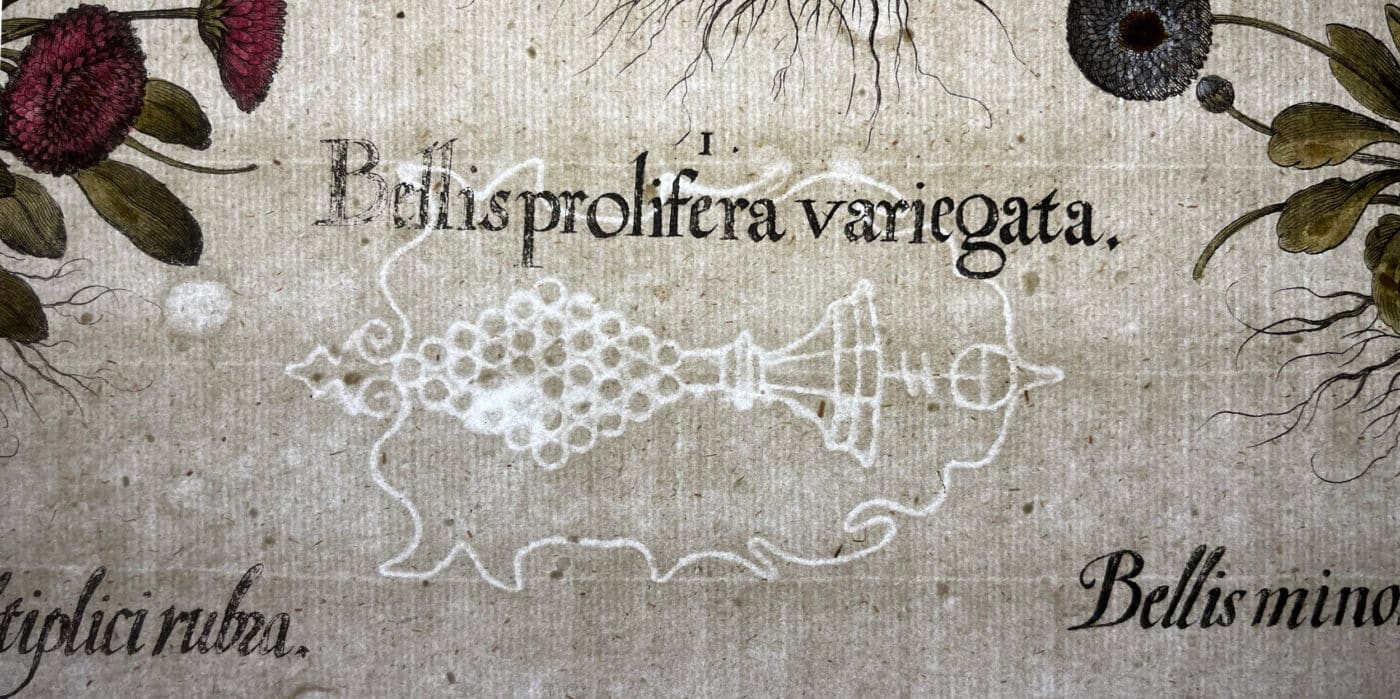

Loft-Drying Creases

Before the mechanization of paper production with the introduction of the Fourdrinier machine in 1799, all paper was handmade and therefore subject to individual variation. One common characteristic of early handmade paper is the presence of a drying crease across the center of the sheet as can be seen below in Basilius Besler’s 1613 botanical engraving. Here, a subtle wrinkle formed during the drying process bisects the sheet. Such creases were formed during the latter stages of the papermaking process during which the newly formed sheets were draped over a rope or thin wooden rod to air dry in the loft. At this point, the still malleable fibers at the center of the sheet conformed to the contours of the rope or rod and caused a wrinkle to form as the paper dried. Such wrinkles tend to be found on older stocks as methods for flattening and finishing paper changed with the introduction of the heated, steam cylinder drying technique in the early 19th century.

Paper was hung in drying lofts until all the excess moisture had evaporated.

Whatman’s drying loft at Springfield Mill

Creases from the air-drying process are often found on antique sheets of paper.

Detail of a hand-colored engraving from Basilius Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis, 1613.

Vatman’s tears are formed by droplets of water falling onto the malleable surface of a newly formed sheet.

Detail of a 1613 engraving on laid paper with several visible vatman’s tears.

Vatman’s Tears

Another incidental quality of some handmade paper stocks is the presence of “vatman’s tears.” Named after the craftsman who managed the vat of pulp, vatman’s tears are areas of displaced fiber caused by water droplets accidentally falling on the surface of the newly formed sheet while it is still wet and assimilative. Revealed only by shining a light through the sheet, these small and circular drips indicate that the paper is handmade rather than mechanically produced.

Watermarks

In contrast to the incidental presence of drying creases and vatman’s tears, a very deliberate attribute of many antique (and modern) paper stocks is the watermark. Often taking the form of a symbol, initial, or name, watermarks have been used in Europe since the 13th century. Watermarks historically served a number of purposes including to identify the producing paper mill, to designate the quality grade or size of the stock, and to serve as a security or authenticity feature.

Typically a sheet must be held up to a light source to reveal the watermark.

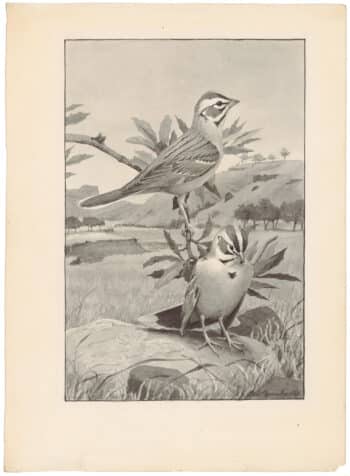

This engraving of Pl. 35, The Little Sparrow from Mark Catesby’s 1754 edition of The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands is printed on laid paper bearing a Fleur-de-lis watermark.

Typically undetectable in ambient lighting conditions, watermarks can be revealed by shining a light directly through the sheet. Watermarks are created in much the same way as chain and laid lines, through the impression of the mould. During this process, the craftsman ties a wire design to the ribbed framework of the mould. Thus, when the pulp is distributed in the mould and begins to consolidate, it retains the impression of the raised watermark design in its fibers. There are a number of incredibly helpful resources for watermark identification referenced below.

Watermarks were typically created by attaching a wire symbol, initial, or word to the wire screen of the paper mould.

Wire watermarks for W.S. Hodgkinson & Company, George Stewart & Company, the South African Government, and Thomas James Hurcott Mill.

It is important to note that sometimes machine-made paper is manufactured to replicate the qualities of antique stock. For example, high-quality stationery is often produced with a facsimile grid pattern modeled after that of laid paper. However, machine-made stock has a rigid, unvarying grid pattern and deckled edge while handmade paper typically bears the nuances of the crafter’s individual touch.

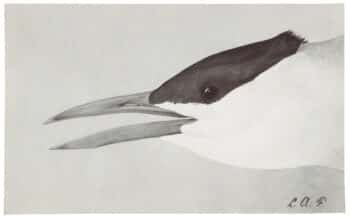

Watermarks can be important aspects of dating and authenticating works on paper.

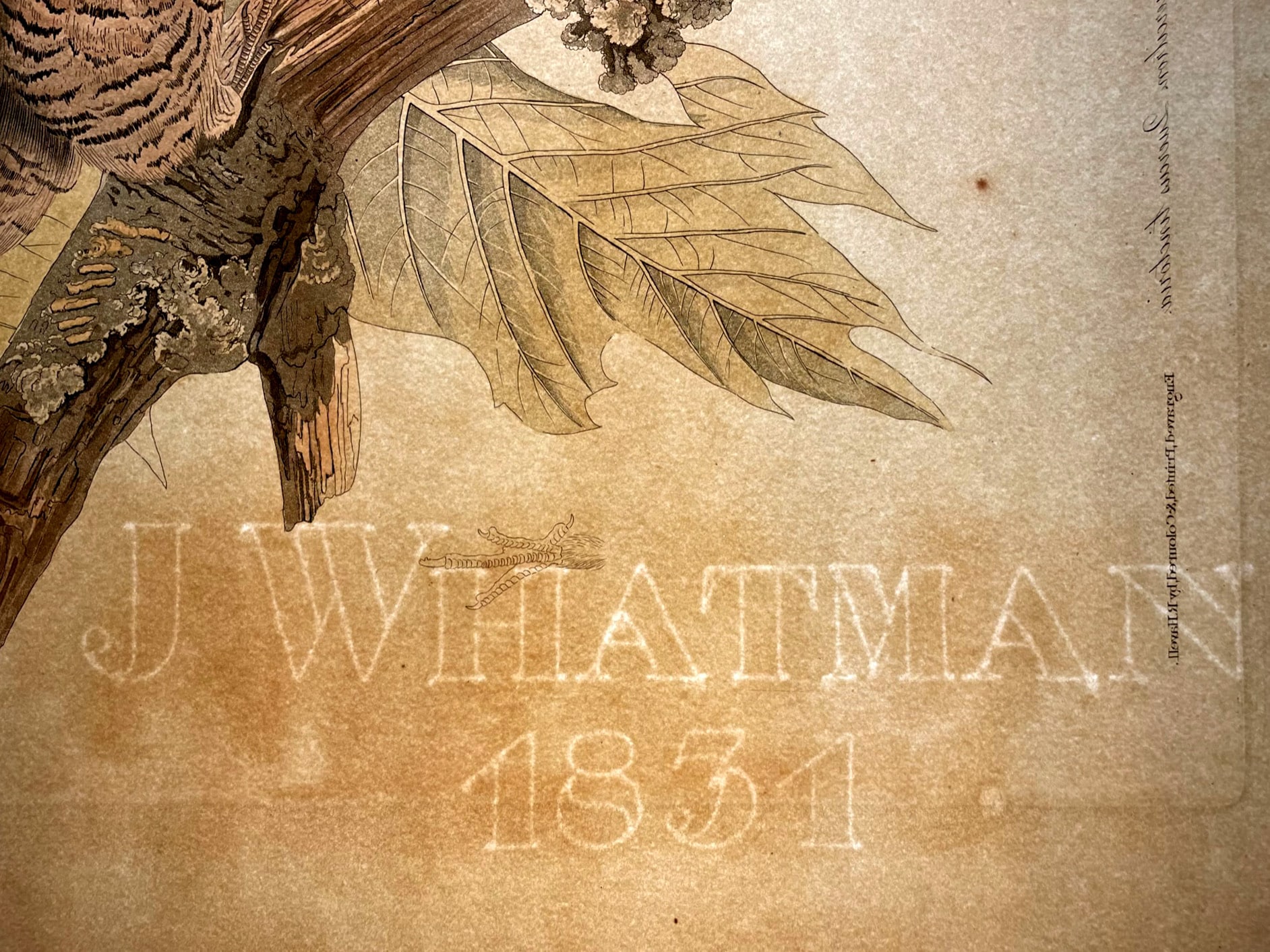

Detail of J Whatman 1831 watermark on Audubon’s Havell edition Pl 82, Whip-poor-will.

view artworkIn conclusion, the charming aberrations and complex material qualities of antique paper often hold stories about its own manufacture. Additionally, understanding the chronology of different paper types, materials, and watermarks can often be important in authenticating works on paper. For instance, all untrimmed John James Audubon Havell edition prints from The Birds of America bear a “J Whatman” or “J Whatman Turkey Mill” watermark. In this instance and many others, the watermark can serve as a concrete attestation to the provenance of the paper and the authenticity of the art. Moreover, by closely examining the paper substrate of an artwork, book, or document, we open ourselves up to a broader understanding of the object through its material characteristics.

References & Resources

Bernstein – The Memory of Paper. https://www.memoryofpaper.eu/BernsteinPortal/appl_start.disp#

Cycleback, David. (February 10, 2013) “Identifying and Dating Paper.” https://davidcycleback.com/2013/02/10/identifying-and-dating-paper/

Harris, Theresa Fairbanks and Scott Wilcox, ed. (2006). Papermaking and the Art of Watercolor in Eighteenth-Century Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Hunter, Dard. (1978). Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Murphy, Heather. (September 28, 2021). “The Imagery of Early Watermarks.” Qatar Digital Library. https://www.qdl.qa/en/imagery-early-watermarks

Müller, Leonie. (May 7, 2021). “Understanding Paper: Structures, Watermarks, and a Conservator’s Passion.” https://harvardartmuseums.org/article/understanding-paper-structures-watermarks-and-a-conservator-s-passion

Vintage Paper Co. (April 7, 2019) “J Whatman – The Master of Western Papermaking.” https://vintagepaper.co/blogs/news/drying-paper-at-whatmans-springfield-mill

Fuertes Original Paintings

Original Watercolor Painting

Fuertes Original Paintings

Original Watercolor Painting

Fuertes Original Paintings

Original Watercolor Painting

Fuertes Original Paintings

Original Watercolor Painting

Descriptions of Egypt

Description de l’Égypte (Description of Egypt) Pl. 8, General View of the Pyramids of the Sphinx

Field Museum Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print Print

Descriptions of Egypt

Description de l’Égypte (Description of Egypt) Pl. 11, View of the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid

Field Museum Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print Print

Audubon's Watercolors - The New-York Historical Society Edition

Havell Edition – Antique Originals

Original Havell double-elephant folio hand-colored Engraving | circa 1827-1838 | 25.25 x 38.625 inches