Birds and Animal Art

The Birds of Paradise: One of Nature’s Most Elusive, Ostentatious, and Promiscuous Families

The Introduction of Birds-of-Paradise to the Western Imagination

Originating from the diverse terrain of New Guinea and its neighboring islands, the birds-of-paradise have attracted and eluded natural historians since their introduction to the Western world in 1522 CE. Recognizable for their flamboyant feathering and sophisticated mating rituals, this family of birds evolved under a unique set of ecological and geographical circumstances that precipitated their splendid appearance and libertine behavior. With the majority of the population cloistered by the varied and insurmountable terrain of New Guinea, the birds-of-paradise, of which there are 42 identified species, remain elusive to this day (Diamond 1986, 20).

![[OFEL1-002]](https://www.audubonart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/OFEL1-002-Elliot-Pl.jpeg)

Pl. 2, Paradisea Apoda, or Greater Bird-of-Paradise

Daniel Giraud Elliot

The allure of the birds-of-paradise captured the Western public’s imagination as early as the 16th century when Magellan’s crew, after circumnavigating the globe, brought back the first bird skins as a gift for the king of Spain. Interestingly, these skins were missing their feet “as was the skinning practice of early Bird of Paradise hunters,” which led Carolus Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, to name the species Paradisaea apoda: the “footless Bird of Paradise” (Johnson 2018, 57). Thus the birds-of-paradise entered the Western imagination as creatures inhabiting “a heavenly realm, always turning toward the sun, feeding on ambrosia and never descending to earth until their death” (Johnson 2018, 57).

Works of art such as the portrait of Young King Charles I (1610) and Peter Paul Rubens’ Adoration of the Magi (1609-1629) include reference to the Paradisea Apoda or Greater Bird-of-Paradise, attesting to its desirability as a rare and exotic commodity. In the portrait of King Charles I by Robert Peake the Elder, the long golden plumes of a Greater Bird-of-Paradise illuminate the upper left quadrant of the painting, competing with young Charles for the viewer’s attention, and signaling its regal status and appeal to the aristocratic palette. Likewise, in Rubens’ Adoration of the Magi, a resplendent Greater Bird-of-Paradise is attached to the jeweled turban of the magi which connotes themes of affluence, exclusivity, and a sense of foreignness.

Jacques Barraband Pl. 16, Le Nébuleux, étalant ses parures

Image Box text

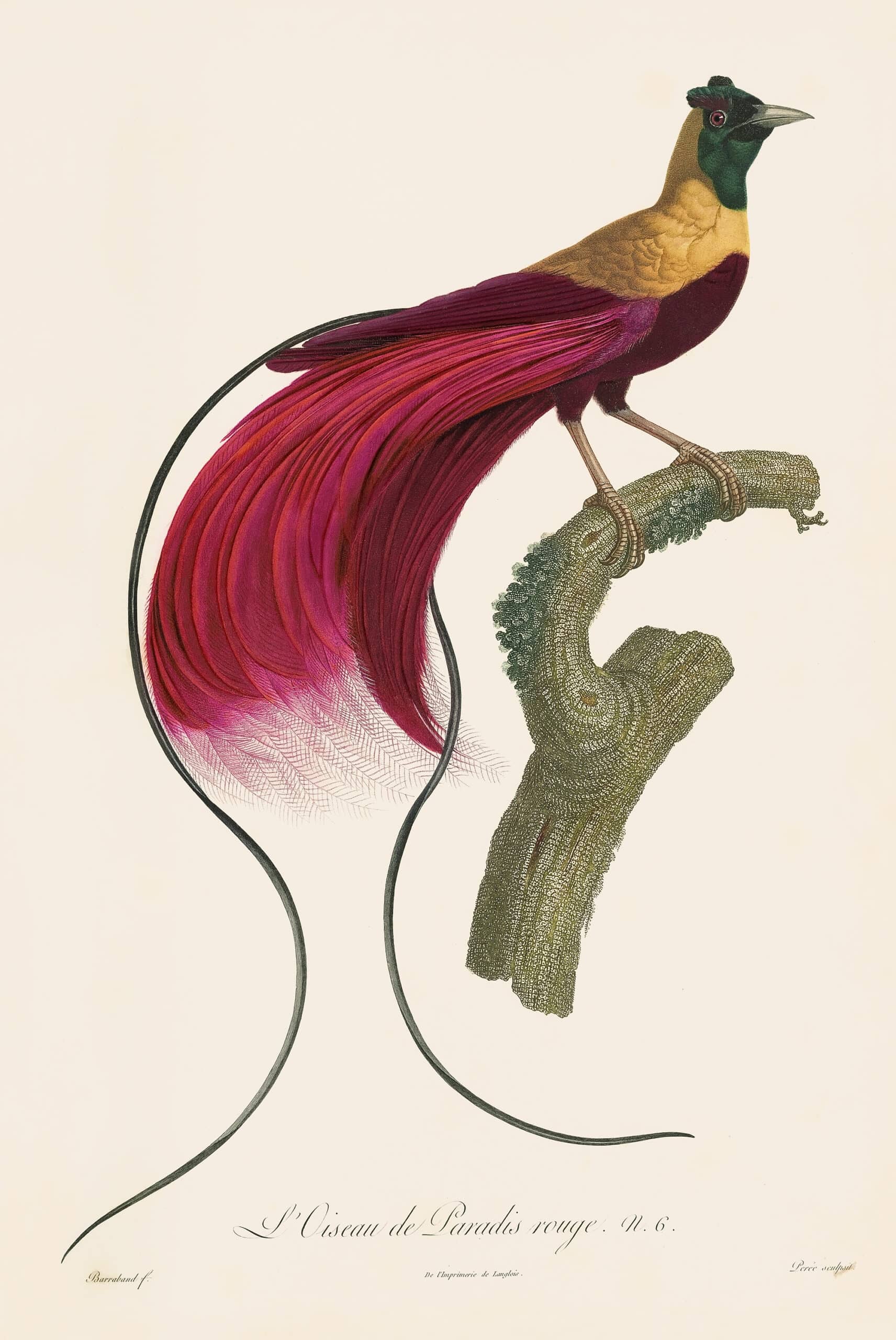

Jacques Barraband Pl. 6, L’ Oiseau de Paradis rouge

Image Box text

By the 19th century, birds-of-paradise remained shrouded in mystery despite the emergence of a robust trade in their feathers and skins which were acquired from Papuan people and traded throughout Europe. “Despite this, very few collectors or ornithologists had ever seen live birds of paradise, and taxidermists and artists used a great deal of license in imagining them from plumes and skins” (Frith and Frith 2010, 131).

In the hand-colored engravings by Jacques Barraband Pl. 16, Le Nébuleux, étalant ses parures and Pl. 6, L’ Oiseau de Paradis rouge, we can sense the artist’s lack of understanding of the bird’s native environment, which is left vacant. Rather, the prints reflect the Western desire for new and exotic consumable curiosities with perhaps less interest in their place of origin. Along with other rare natural curiosities, birds-of-paradise were collected as part of personal menageries and cabinets, which were “regarded as one of the essential furnishings of every member of the leisured classes with claims to be considered cultivated” (Allen 1994, 26).

![[OFEL1-020]](https://www.audubonart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/OFEL1-020-Elliot-Pl.jpg)

It was not until the mid-19th century when British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, after spending 8 years collecting natural specimens in the Malay Archipelago, finally observed a live bird of paradise in the wild. He subsequently brought two live male birds of paradise back to England along with the reservoir of preserved specimens he has amassed. In recounting his experience looking for birds-of-paradise in New Guinea, Wallace mused: “It seems as if Nature had taken precautions that these her choicest treasures should not be made too common, and thus be undervalued. . . . The country is all rocky and mountainous, covered everywhere with dense forest, offering in its swamps and precipices and serrated ridges an almost impassable barrier to the unknown interior”(Wallace 1869, 439).

With no natural predators or competitors for food on the island, the sexually dimorphic birds-of-paradise had an abundance of leisure time. From an evolutionary standpoint, this unique environment allowed the males to direct their abundant energy towards developing conspicuous plumage and elaborate mating practices in pursuit of female birds, who don a more modest coat. Their evolutionary adaption is perhaps all the more impressive when one learns that birds-of-paradise share a common lineage with the family Corvidae or Crow.

Elliot Pl. 19 Great Sickle-bill

Hand-colored lithograph with gold leaf

Elliot Pl. 19 Great Sickle-bill

Uncolored lithograph with gold leaf

In Daniel Giraud Elliot’s depiction of the Epimachus Speciosus Pl. 19 Great Sickle-bill (above), we observe a male performing for a female, who, perched discerningly in the background, looks somewhat unamused by his antics. Chest puffed and wings extended, the male bird’s dramatic posture emphasizes its glossy feathers which Elliot has enhanced with the inclusion of a gold leaf underlay beneath the iridescent crown and wing bands. The gold leaf causes the artwork to glint and glisten, and we catch a breath of movement as the bird shimmers as though alive.

Likewise, in Elliot’s Ptiloris Paraddiseus or Pl. 25, Paradise Rifle-bird (above), we see two colorful males competing for the attention of a female. All three birds confront us with steady, apathetic stares, suggesting that we may have walked into something private. The central male appears confident in his upright posture while the male at the bottom of the composition appears somewhat dejected. Perhaps we can infer who won the favor of the female. Again Elliot uses gold leaf to highlight the iridescent crown, breast, and tail feathers of the male bird’s plumage.

Many times, the mating rituals of the polygamous birds-of-paradise species include the construction of a nest-like structure, known as a bower, that the male crafts and decorates with enticing items such as shells, flowers, fruits, stones, and other natural objects. Male birds are even known to pilfer from one another’s bowers in an attempt to produce the most desirable structure to entice potential mates.

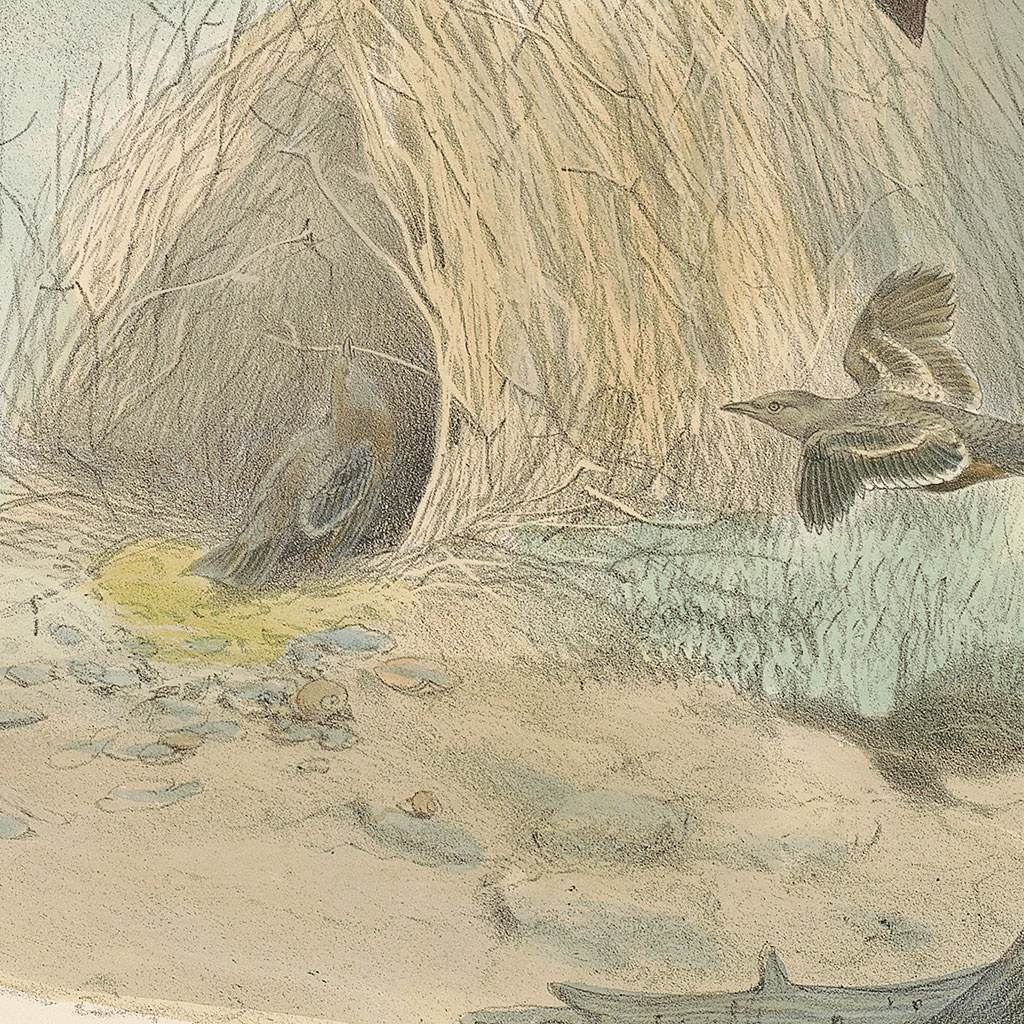

In Elliot’s Pl. 32, Buff-breasted Bower-bird, the bower-building tendency of the species is indicated in the background of the composition where a male bower-bird actively constructs a reed hut. Polymath Jared Diamond observes that adolescent males, who have not yet developed the highly ornate feathers of mature birds, “spend much time watching at bowers of older males and even assume the female role in courtship displays with adult males” (Diamon 1986, 34).

In fact, it has been theorized that the male bird’s promiscuous tendencies and lack of discernment in the direction of its advances have led to species hybridization. In other words, the males are likely to mate with any females that respond favorably to their displays regardless of whether or not they are of the same species.

Interestingly, the birds-of-paradise family proved instrumental in informing human understanding of evolutionary biology. In fact, after years of observing species in the Malay Archipelago, and while delirious from malaria, Wallace developed a theory of natural selection and the biological adaption of organisms in response to their environment. Wallace came to this conclusion simultaneously to but independently from his friend and colleague Charles Darwin who published On the Origin of Species in 1859. Thus, the birds-of-paradise acted as key exemplars of evolution and natural selection.

Allen, David Elliston. 1994. The Naturalist in Britain: A Social History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Darwin, Charles. (1859) 1968. The Origin of Species. Harmondsworth:

Penguin.

Diamond, Jared. 1986. “Biology of Birds of Paradise and Bowerbirds.”

Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 17:17–37.

Frith, Clifford B., and Dawn W. Frith. 2010. Birds of Paradise: Nature, Art,

History. Malanda, Australia: Frith & Frith.

Johnson, Kirk Wallace. 2018. The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century. New York: Viking.

Wallace, Alfred Russel. (1869) 1962. The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the

Orang-Utan and the Bird of Paradise. New York: Dover.