Information

A Comparative Analysis of Poiteau and Brookshaw’s Pomological Prints

A consideration of the aesthetic, technical, and didactic components of Poiteau and Brookshaw’s depictions of fruit.

Table of Contents

- The Artists’ Work in Dialogue

- Technical Approach to Rendering Fruit

- Instructive and Aesthetic Intentions

The work of contemporaneous artists Pierre-Antoine Poiteau and George Brookshaw converge on a number of levels, and elevate pomological investigation to an aestheticized strata. Subject matter and technique are a point of commonality between the two artists, and yet the overall effect of their individual work is quite different.

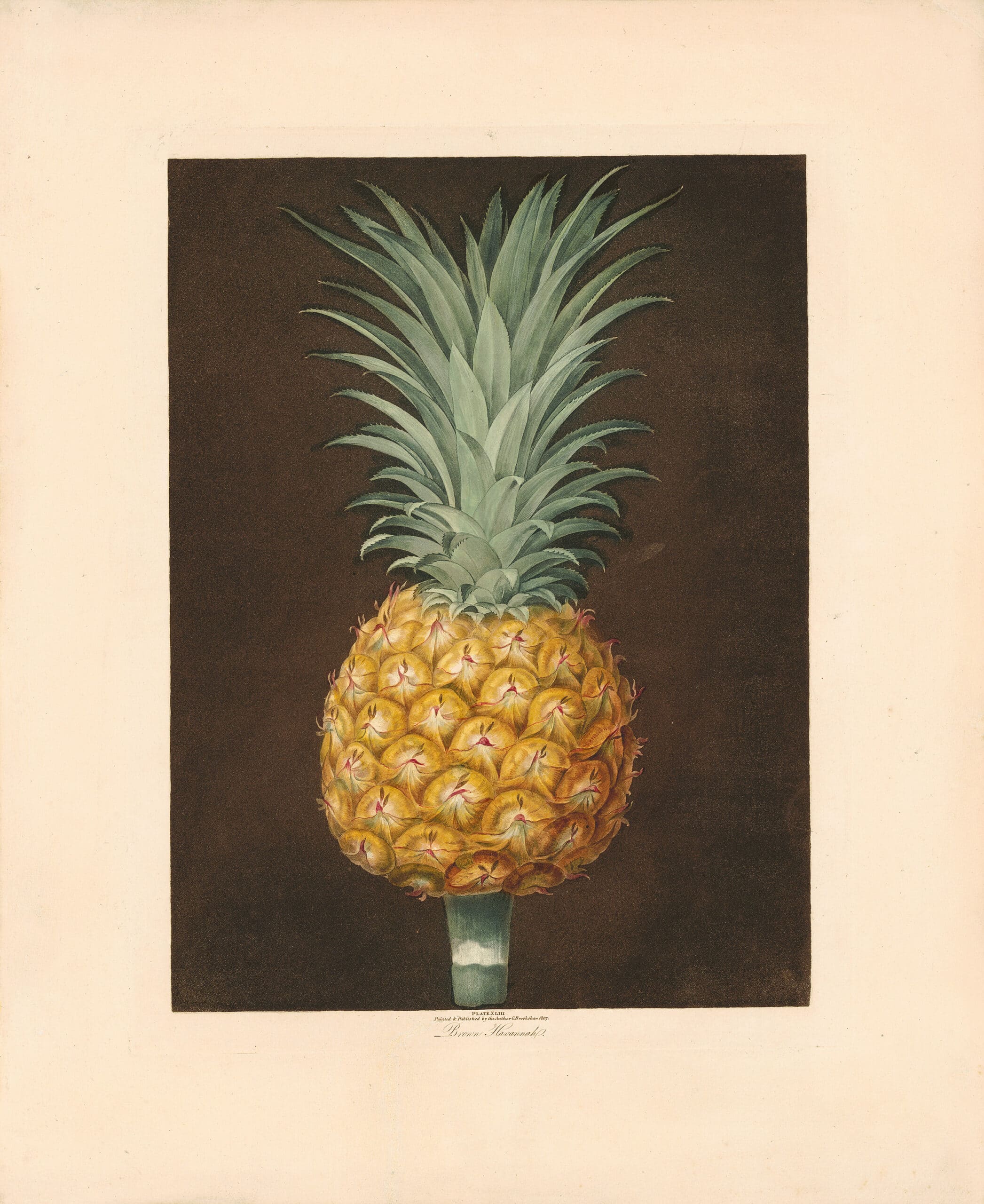

Pl. 43, Brown Havannah

George Brookshaw

Pl. 203, Plaqueminier de Virginie

Pierre-Antoine Poiteau

The Artists’ Work in Dialogue

While Poiteau’s prints appear light and airy, Brookshaw’s are often grounded with monochrome backgrounds, shadows, and a greater sense of depth. Yet the greatest distinction between the two artist’s work is that Brookshaw’s depictions focus on the untarnished mature fruit, while Poiteau’s rendering attempts to understand both the interior and exterior structure of the fruit as well as it’s maturation process.

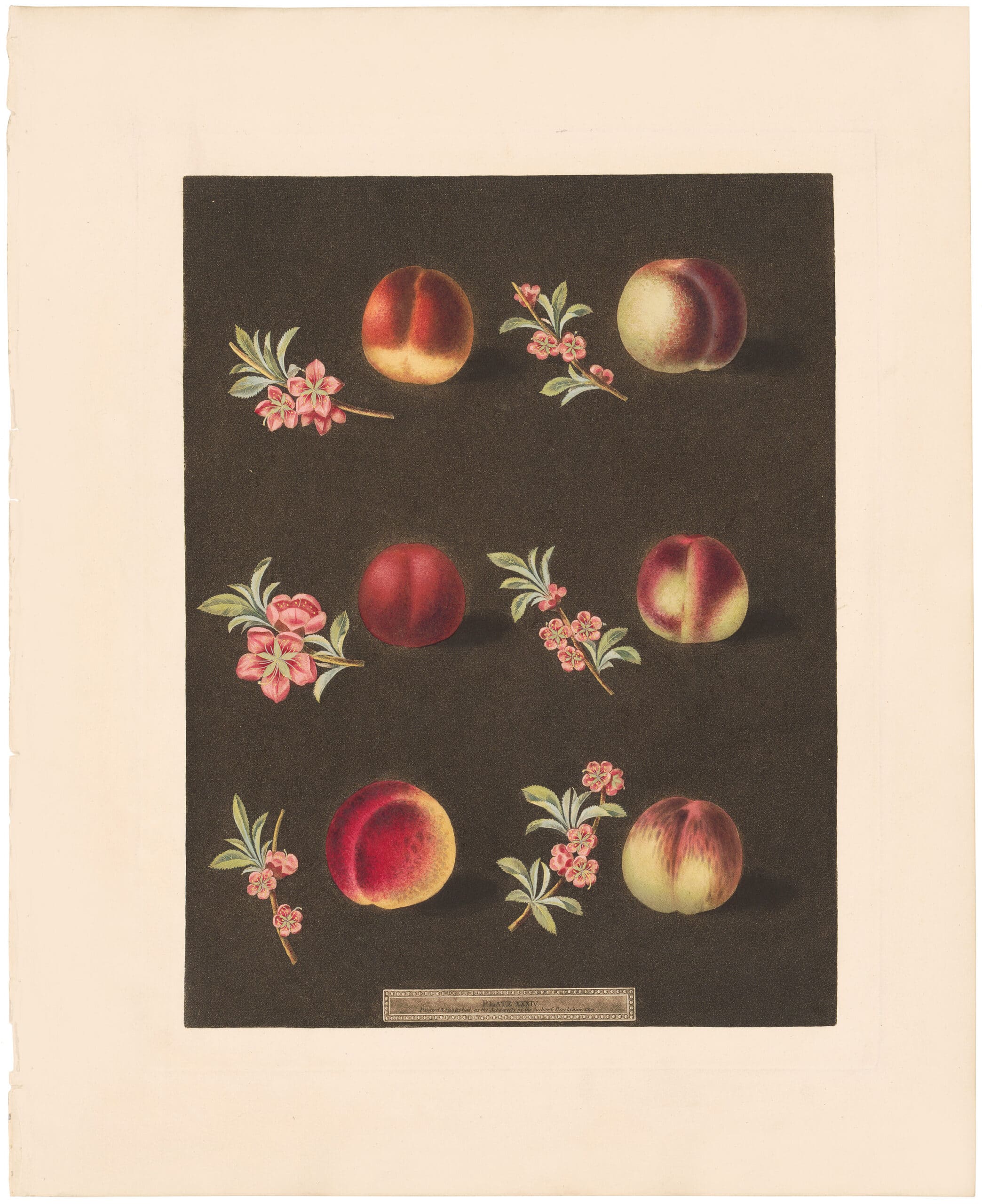

Take for example Brookshaw’s Pl. 34, Peach/ Nectarine – Vermash/ Violet et al. in which we are presented with six peaches arranged with a strong sense of design in three rows of two. A slight shadow near the base of each fruit gives them a sense of presence and density. Additionally, to the left of each fruit its correlative blossom is depicted. The dark umber of the background highlights the vibrant hue of the fruit, and emphasizes their texture and brilliance. In fact, they appear to glow against the dark backdrop.

Pl. 101, Prunier Ile-verte

Poiteau

In contrast, Poiteau’s Pl. 101, Prunier Ile-verte is incredibly lithe and pictures the ceraceous fruit still clinging to its branch. In addition, not only is the related flower blossom depicted, but also a view of the fruit sliced open with its stone exposed. Poiteau’s fruit is suspended against a blank background, and has little emphasis on the spatial coherence of the composition. Instead, Poiteau employs the empty space to not only emphasize the contours and colors of the fruit, but also to give it a sense of weightlessness.

Technical Approach to Rendering Fruit

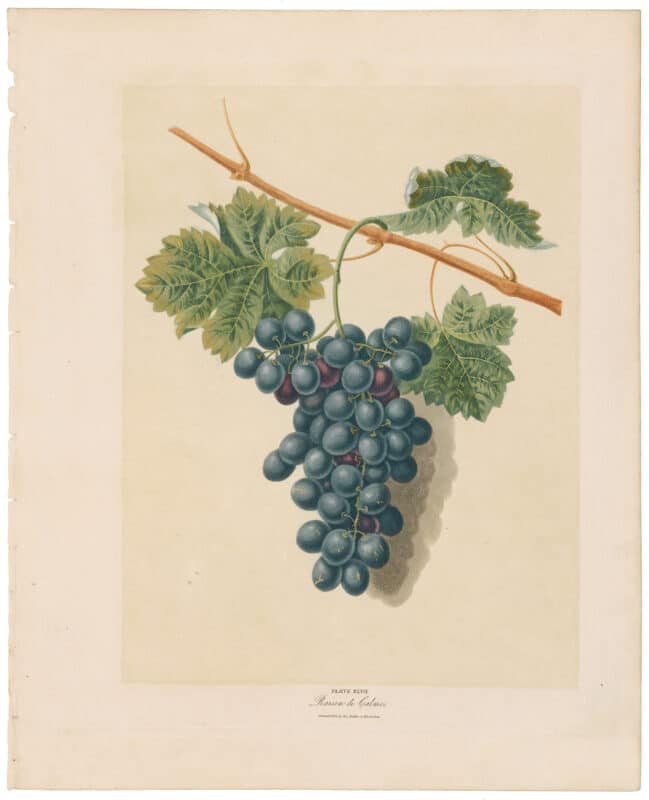

Interestingly, both artists engage with the same printing technique in their work, that of stipple-engraving. This printmaking process involves the use of a sharp or blunt roulette point, which is used to create uniform dots or dashes in the copper plate where the ink will be retained. This method differs from line engraving in that the indentations impressed upon the plate are dots rather than continuous lines. The overall effect of this technique renders the fruit soft, supple, and without harsh contour lines as can be seen in this close-up image of Poiteau’s Pl. 209, Groseiller a grappes (fruit blanc), and Brookshaw’s Pl. 47, Grapes – Raison de Calmen. In addition, both artists make use of softer colored inks in muted shades such as brown, blue, and green rather than the standard black ink.

In opposition to Poiteau, Brookshaw then further developed his prints with a process called aquatint, which accounts for the continuous tones of his solid backgrounds. Additionally, he used both line and stipple engraving to nuance the textures and contours of the fruit. After the printing process, the works of art were then hand-colored with watercolor, often mixed with opaque white, in order to capture the fruit at peak ripeness and delectability.

Poiteau, on the other hand, implemented color into the printing process itself through a technique called à la poupée. In this technique, a cloth daubing pouch is used to color the copper plate which is then run once through the press, resulting in a colored print. These prints are then “finished by hand” as watercolor is used to add the final touches.

Pl. 17, The Blue Passion Flower

Thornton

Within the scope of 18th and early 19th century botanical, floral, and pomological prints, Brookshaw and Poiteau have direct creative antecedents. While Brookshaw exemplifies certain characteristics that are found in the florilegium of Robert Thornton, a British physician and botanist who was the creative force behind the Temple of Flora, Poiteau’s renderings demonstrate a clear lineage from the work of French botanical artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté, who was favored by both Marie Antoinette and later Empress Joséphine Bonaparte. In this way, both artists espouse certain stylistic standards native to their respective cultural and regional spheres.

Instructive and Aesthetic Intentions

Brookshaw and Poiteau both had similar pursuits with their works, Pomona Britannica 1812, and Pomologie Français 1846. Both books were intended to be didactic references for botanists, pomologists, gardeners and horticulturists, while also remaining aesthetic and enchanting objects. In fact, Brookshaw outlined the specific demographic he was catering to in the preface to his 1817 “popular” edition of Pomona Britannica:

“It is the primary objective of the present work to excite Gentlemen themselves a predominant turn and ardor…for this elegant, entertaining and highly important subject…,to direct and superintend their own gardeners or labourers, instead of being…the sport of their ignorant pretensions…It is the Fruit-garden only…that is hung, after the fall of the blossoms, with a rich harvest of rainbow hues, and gives us, as Agricola exclaimed, amid the artificial walks of Versailles, a foretaste of Paradise.” (Janson 1996, 288-289).

Brookshaw indicates that the book is to function as an instruction manual for cultivating the horticultural tastes of Gentlemen, who are to then instruct their garden staff to implement their newly refined preferences.

Poiteau’s intentions for his book are less clearly defined, but follow a similar sentiment. Through identifying, naming, categorizing and depicting fruits, Poiteau sought to develop and standardize this nascent branch of botany. In his prints he employs meticulous detail and often fully dissects the fruit in question so as to make it undeniably comprehensive for the viewer, as can be seen in Plaqueminier de Virginie, or Common Persimmon, Pl. 203. In fact, his prints appear to cater to the knowledgeable viewer who might recognize and make use of the highly detailed renderings of the fruit, its interior, leafy accoutrement, seeds and blossoms. These aspects of the fruit suggest an interest in propagation and cultivation, rather than mere contemplation or consumption.

In conclusion, both Brookshaw and Poiteau’s artwork are placed in dialogue through their subject matter, technique of rendering, and contemporaneous manufacture. Additionally, both artists present the fruit in an aesthetic as well as a didactic manner, with the intention to evoke something beautiful and to encourage it’s propagation. However, while Brookshaw’s Pomona Britannica is intended to cultivate the tastes of higher class gentlemen so that they might instruct their gardeners, Poiteau’s Pomologie Français appears to cater to a knowledgeable horticulturist. In fact, Poiteau’s depictions are arguably more pragmatic for gardening purposes since they show the seeds of the fruit, it’s nascent bud, foliage, and other identifying factors.