Botanical Art

Basilius Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis or Garden of Eichstätt

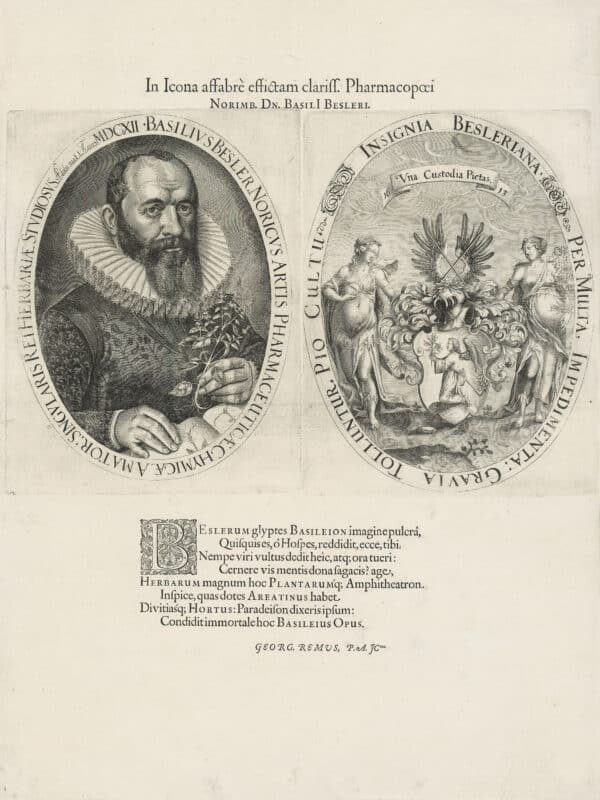

Published in 1613 by Nuremberg apothecary Basilius Besler, the monumental florilegium Hortus Eystettensis artistically records the flowering contents of the Garden of Eichstätt. Cultivated by Prince-Bishop Johann Konrad von Gemmingen at his Bavarian residence, this garden boasted foreign flora from all over the known world.

Table of contents

Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis constitutes 367 lavishly detailed engravings that capture the most beautiful and exotic plant life cultivated there. Rendered on large sheets of 22 ½ x 18 inch paper, Besler’s engravings emphasize the ornate qualities of the plants as he traces their progression throughout the seasonal calendar. As a result, his engravings act as a monument to ephemerality in that they place emphasis and gravity on the temporal qualities of the plants, and their inevitable tendency to grow and decay. Moreover, the florilegium acts as an artistic catalogue of a singular garden, the Garden of Eichstätt, and in doing so, preserves the landscape of a very particular temporal and geographical space viewed through the lens of the plant life cultivated there.

Historical Significance of Cultivating & Rendering Plants

In the late 16th century, gardens became a manner through which wealthy and powerful individuals could display their influence and intellectual engagement by acquiring and cultivating foreign plant life. Additionally, as Gill Saunders points out in his book Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration, “This was an age when flowers were increasingly grown purely for their decorative properties, their colours and forms, and not as previously for their practical uses in medicine and cookery.” Furthermore, “the production of florilegia was a response to the wealth of new plants, and in particular the colorful showy exotics, that were arriving in Europe from the southern and eastern Mediterranean regions, north Africa and the Americas, from the second half of the sixteenth century” (Saunders 1995, 41). Besler’s florilegium exemplifies this transition from a functional to an aesthetic appreciation of plants through the primacy of imagery over text in his book.

Ornamental and Functional Flora

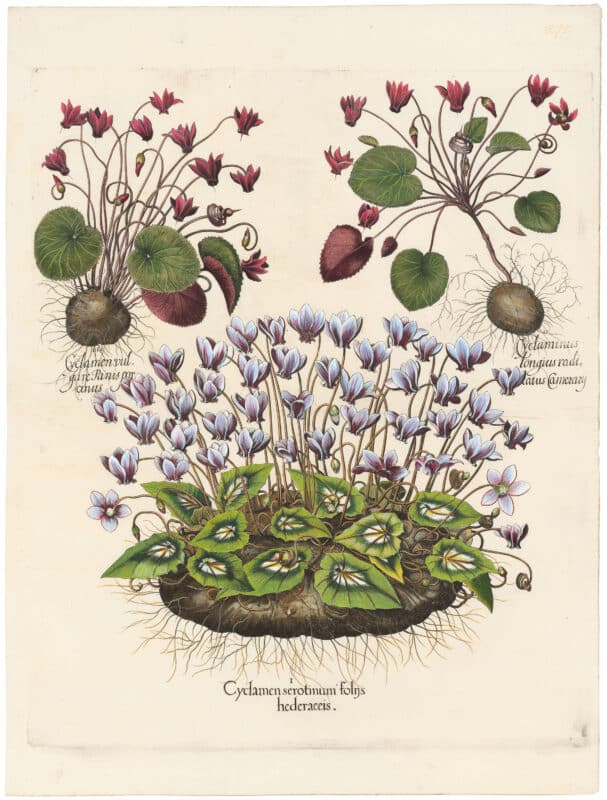

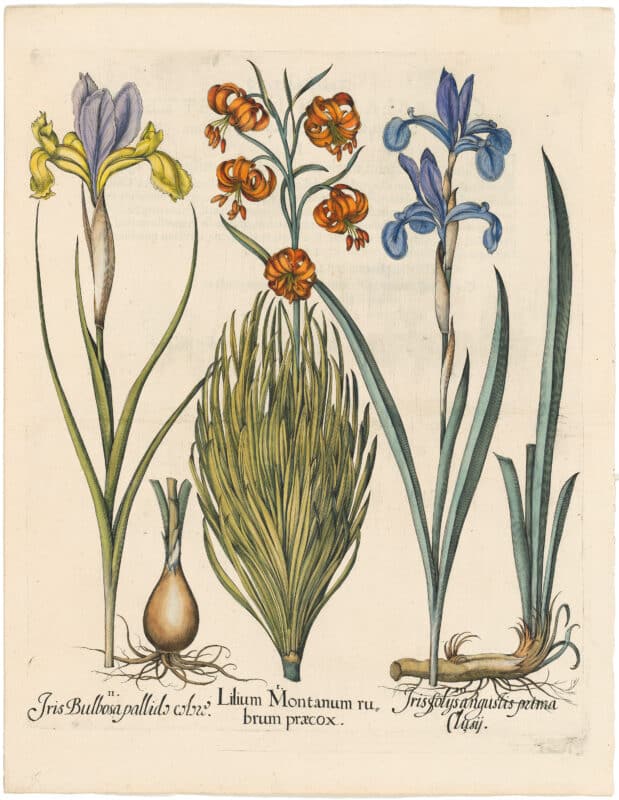

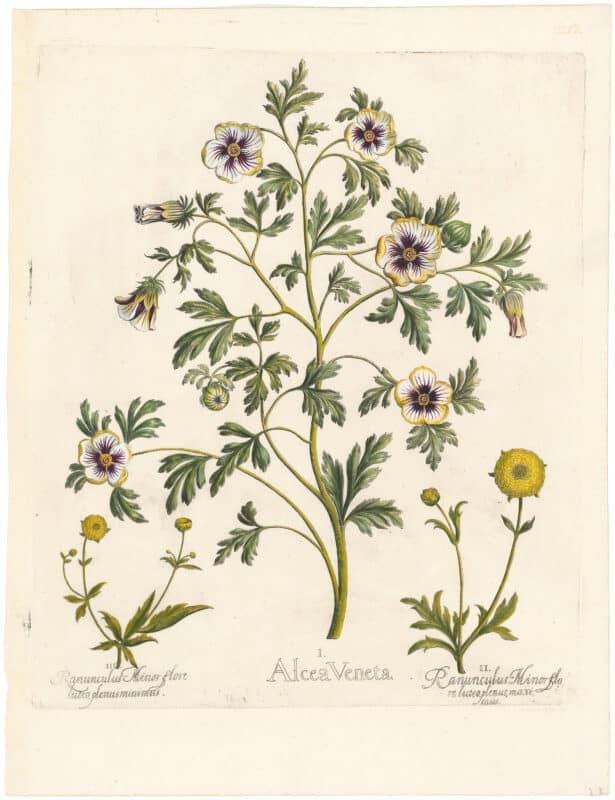

Take for example Flower-of-an-hour, Double-flowered Buttercup, et al., Pl. 217, Deluxe Edition, in which three floral sprigs are delicately placed against a blank backdrop. The symmetry and orientation of the flowers indicate a strong sense of design behind Besler’s compositional choices. Likewise, each flower is presented in order to exhibit its most attractive attributes. The central flower, the flower-of-an-hour, yawns and stretches its foliage out across the page. Likewise, the two buttercups, set in perfect harmony on either side of the composition, genuflect in reverence to the central blossom.

The fragility of the sprigs, leaves, and petals is exacerbated by the delicacy of the paper itself, which bears the impression of the copper plate as it was run through the printing press. Likewise, there is a tactility lent to the artwork by the engraving process which leaves not only the plate embossment, but also delicately raised linework. In this way, running one’s hand across the page is somewhat similar to experiencing the sensorial engagement of a crepe-like flower or veiny leaf itself. Furthermore, the diaphanous watermark, the pomme de pin, found on many sheets of Besler’s Deluxe Edition likewise adds to the delicacy of the overall effect. Lastly, the calligraphic writing below each flower delineating its Latin nomenclature further augments the elegance and ethereal nature of the print.

In addition to decorative and ornamental flowers, Besler’s printed garden includes plants that serve a traditionally functional purpose. For example, Red peppers with long yellow, nodding fruit, Pl. 327, Deluxe Edition, captures the edible vegetable but transforms it into an aesthetic object. Two plants with a strong vertical orientation have been plucked from the ground, and now lay before us, roots exposed, for our visual delectation. A small truncated area between the stem and the root indicates that Besler has taken creative liberty in order to show us the whole form of the plant while sacrificing a portion of the tall stem for the inclusion of the roots. This approach was common in scientific illustrations of botanical and zoological specimens for centuries after Besler.

Creative Methodology

Besler’s approach to visually cataloging this extensive floral collection was methodical and required the aid of many draftsmen, printmakers, and botanists. Located in Nuremberg, Besler’s required many of the plant specimens to be shipped to him from Eichstätt, in Bavaria, Germany, whereupon he would begin the sketching process. In addition, he planted a garden behind his Nuremberg apothecary where he cultivated many of the plants found in Eichstätt so that he might observe their growth and development, and make use of fresher samples.

Publication

When it came to the final publication of the book, sixteen years after its inception, Besler’s patron, Johann Konrad von Gemmingen – Prince Bishop of Eichstätt – had already passed away. As a result, Besler strategically devoted his second edition of the book to the Bishop’s successor, Bishop Christoph, in order to garner support for the expensive publication. In 1613 three editions of the book were issued. Angus Carroll explains how Hortus Eystettensis “was not only one of the most expensive books of the early seventeenth century but with each leaf measuring 570 x 460 mm. (approximately 22 ½ x 18 in.), the largest” (Carroll 2009, 391). A deluxe copy was 500 florins (the price of a small house), while an uncolored copy was 35 florins. With 367 plates depicting over 1,000 species of plants and flowers, this massive undertaking documenting a single garden was one of the first books of its kind. Even today, the physical garden at Eichstätt has been revived and preserved largely due to the keen visual records kept by Basilius Besler.