Botanical Art

“A Genteel Diversion” – Unearthing the Complex History of Women and Botanical Art

The relationship between women and flowers has been longstanding and laden with social inflections concerning gendered expectations, sexuality, class, and moral standing. In ancient times, women were often likened to botanical imagery because of the poetic connotations of fertility, delicacy, and beauty common to both parties. Likewise, in the 17th century, knowledge of plant life was a necessary attribute of a married woman who was expected to act as the household healer. By the Enlightenment, women’s study of botany accrued moralistic undertones and was promoted as a suitable activity for their “moral and spiritual development” (Shteir 1996, 2). This essay will examine the dynamic and often contradictory relationship between women and botany.

Prior to the development of botany as a distinctive discipline, the study of plants often went hand in hand with the study of medicine. Many of the observations made and information gathered on the benefits and consequences of plant compounds can be attributed to women who fulfilled the role of domestic healer in Early Modern Europe. Though credit was scarcely given, women contributed significantly to forming the foundations of medicine through their insights into plant life.

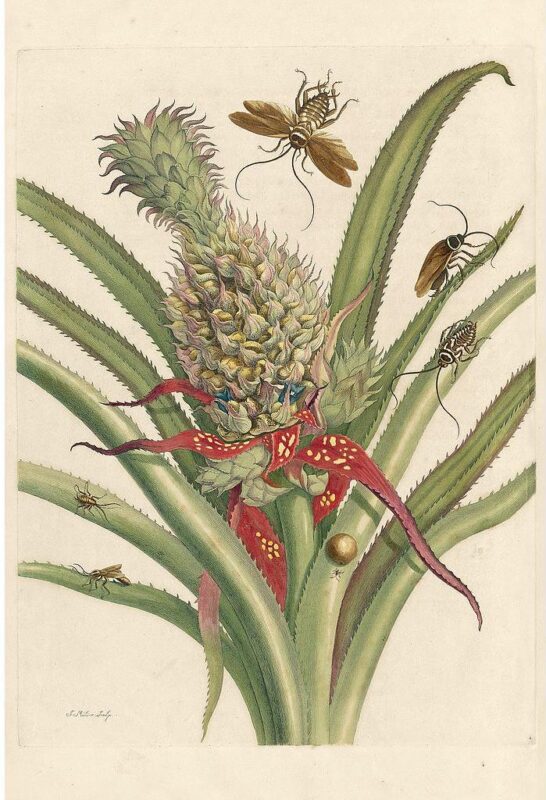

Maria Sibylla Merian

One early contributor to the study of plants (and insects) is artist Maria Sibylla Merian. Born in 1647 in Frankfurt, Germany to a family of artists, Merian’s talent was welcomed and cultivated. However, despite her family’s amenable stance on her artistic pursuits, Merian’s training as an artist differed significantly from that of her brothers. While male artists were encouraged to paint large-scale history paintings and representations of the nude body, these genres were strictly forbidden for female artists. Likewise, a major aspect of a young artist’s training was traveling to different sites and workshops in places like London, Paris, Italy, and Amsterdam. Merian, however, was kept home to learn the domestic duties expected of a woman of her time.

Despite the gendered restrictions placed on her training, Merian flourished as a successful artist. She directed her creativity toward the study of insects in their environment and at the age of 52, she ventured to Suriname where she recorded the developmental stages of insects and published her findings in The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname. Her valuable observations not only on the insect life but plant uses by the native peoples proved valuable and historically fundamental to entomology and botany.

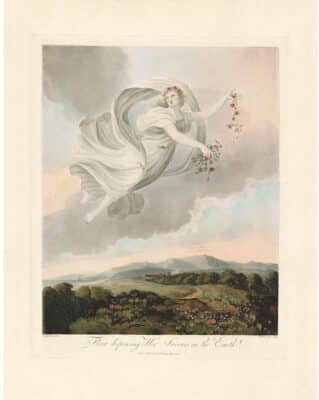

Dr. Robert Thornton

By the 1780s, the close association between women and plants continued to be perpetuated in a number of ways. Some saw botany as “aesthetically concordant with feminine beauty or elegance or delicacy.” (Shteir 1996, 35). Robert Thornton’s Pl. 2A, Flora dispensing Her Favours on the Earth, though a 19th-century print, harkens back to Ancient Roman mythology through representation of the goddess Flora. Flora was the deity of spring, fertility, and flowering plants. Perhaps one of her most notable representations is in Botticelli’s Primavera or “Spring.” Thornton’s print evinces not only the Enlightenment fondness for classical revival in the arts but also the perpetuated association between women and flowers centuries later.

Ann B. Shteir, professor of humanities and women’s studies at York University, suggests that “botany accorded with conventional ideas about women’s nature and “natural” roles. It fit the gendered assumptions of many writers and cultural arbiters about women and domestic ideology and was thought to be a way to shape women, or shape them better, for their lives as wives and mothers” (Shteir 1996, 35). Moreover, the promotion of women’s study of botany had somewhat of a moralistic underpinning in that the popular conceit was that by examining elements of the natural world, the woman would come to better appreciate God’s creations and therefore develop morally and spiritually.

Initially, an interest in botany also reflected a woman’s social class in that the ability to read Latin, the language of the elite, was necessary to access the contemporary discourse on botany. Likewise, during the early days of the Enlightenment, “drawing skills belonged to the roster of conventional accomplishments for girls of higher social class” and “floral drawing parties replaced traditional needlepoint gatherings” (Shteir 1996, 41) (Kramer 1996, 28).

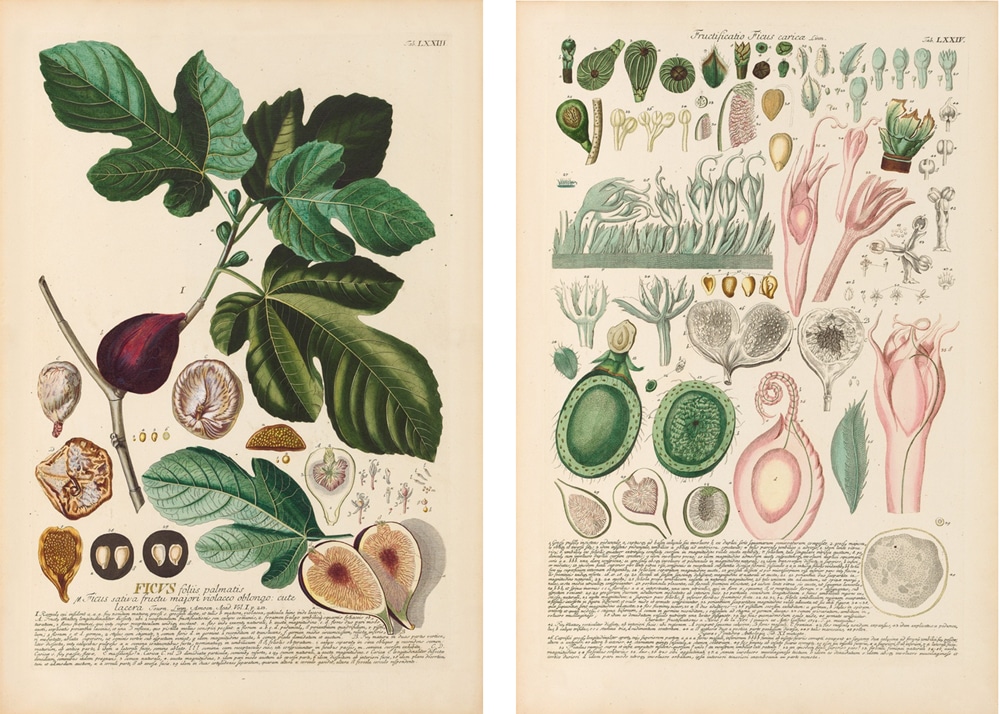

Pl. 73 Fig Tree and Pl. 74 Fig Tree Detail from Plantae Selectae

Georg Dionysius Ehret’s illustrations of the sexual characteristics of the fig tree demonstrate the influence of Linnaeus’s classification system

However, with the popularization of Swedish Botanist Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae and his development of a plant taxonomy based on the sexual systems of organisms, for a short period of time, botany became “an emblem of questionable politics for those whose gender ideology excluded women from sexual knowledge or who equated sexual knowledge with practices discordant with their ideas about femininity” (Shteir 1996, 27).

Pl. 26 Shining Amaryllis

Priscilla Susan Bury

Mercifully, this sentiment was short-lived and the study of botany became increasingly democratized among the genders and classes. “Between 1760 and the 1820s, women crossed the threshold into the botanical culture in growing numbers, and botany became increasingly a feminized area, marked as especially suitable for women and girls” (Shteir 1996, 50). A great number of female botanical illustrators contributed, often without credit, to successful magazines including Maund’s Botanic Garden and Curtis’s Botanical Magazine.

Among these unnamed artists are Priscilla Susan Bury and Clara Maria Pope. In addition to anonymously contributing her illustrations to magazines, Bury published her own book on lilies and amaryllises titled Selection of Hexandrian Plants (1831—34). Others elected to publish anonymously as “In Victorian England, a lady’s name was considered sacred and…not to be used for crass, commercial purposes” (Kramer 1996, 49). Similarly, Pope enjoyed a successful career as a botanical painter and later became an art instructor to several royal personnel including the Duchess of St. Albans and Princess Sophia of Gloucester.

Rothschild’s Slipper Orchid

Heeyoung Kim, Original Watercolor on Paper

Modern and contemporary women artists who embrace plant life as the primary subject of their art include Margaret Mee and Heeyoung Kim. Mee is notable for her significant contributions to the conservation movement and consistently worked throughout her life to promote awareness of the ecological destruction taking place in the Amazon rainforest where she took her inspiration. Likewise, Kim is a botanical artist, instructor, and native plant advocate who uses her wildflower paintings to document the native plants of Midwestern prairies and woods, many of which are rare and endangered species. These women approached botanical art on their own terms and were not operating under the same pressures as their predecessors. Rather, they utilized plant portraits as instruments of advocacy and a means to express their creativity.

In conclusion, the history is women and botany is long and complex, revealing at times systems of suppression, and at others, acts of agency and advocacy. To learn more about the women artists in our collection, please visit the links below.

![[OKME-007] Mee Pl](https://www.audubonart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/OKME-007-Mee-Pl.jpg)

A title

Image Box text

References:

- Davis, Natalie Zemon. 1995. Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

- Kramer, Jack. 1996. Women of Flowers: A Tribute to Victorian Women Illustrators. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang.

- Shteir, Ann B. 1996. Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England 1760 to 1860. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.