Birds and Animal Art

Was Alexander Wilson’s Art Precursive of the Modern Field Guide?

An examination of the stylistic qualities of Wilson’s art in relation to modern standards of field guide illustration

Alexander Wilson (1766-1813) was among the first artist-naturalists to produce an illustrated folio that sought to encompass the avifauna of North America, which he aptly titled American Ornithology (1808-1814). While his folio was soon after eclipsed by the scope and success of John James Audubon’s monumental production on the same subject matter and published only a few years subsequent to his own, Wilson’s art possesses certain visual elements that are reiterated today in the codified visual vocabulary of field guide illustration. These elements include his use of a stylized visual language, the grouping of related species in the same composition, and the inclusion of didactic diagrams. In this way, Wilson’s art demonstrates distinctive semantic similarities with the illustrations found in modern field guides.

‘Shotgun Ornithology’

It is significant to point out that the ornithology of the 19th century looked very different from that of the 20th century. In the days of Audubon and Wilson, it was common practice for an ornithologist to shoot the desired bird in order to examine it more closely or to rely on a skin or taxidermied specimen in an existing collection to learn about the species. This approach to the study of birds was aptly termed ‘shotgun ornithology’ in reference to the fateful method of acquisition. Moreover, the popularity of bird specimens as decorative features in Victorian parlors and as sartorial accessories inflated the demand for mass quantities of new and exotic ornithological specimens.

Conservation Efforts and Field Guides

In contrast, the 20th-century school of ornithology brought with it a heightened awareness of the fragility of natural resources and the necessity of implementing a new means of examining birds that did not result in population diminishment. Fortunately, as technological advances were made in optics, binoculars gained popularity as ideal devices for field observation that did not require the physical acquisition of the bird in order to examine it. This new method of field observation was accompanied by the production of field guides that outlined the various bird species in a condensed manner so that naturalists could visually confirm the bird’s identity by referencing the illustrated guide. Even after the advent of photography, illustrated field guides remain more popular because of their simplified depictions of birds that make identification straightforward.

Portrait of John James Audubon painted by his son John Woodhouse

Though produced a century prior to the popularization of illustrated field guides, Wilson’s art shares important stylistic and iconographic similarities with modern field guides. To begin with, in his hand-colored engravings, Wilson tends to render the bird in profile so that its contours and coloring are easily identifiable. Additionally, many times Wilson groups visually similar species together in the same composition which facilitates cross-referencing. Lastly, the minimal environmental factors depicted in many of Wilson’s prints demonstrate a similarity with the simplified iconography of field guide illustration.

Identifying a Species

For example, Wilson’s 1st Edition, Pl. 4 Orchard Oriole delineates the male and female birds at various stages of maturation and with the corresponding plumage. The dark orange mature male oriole crowns the composition, followed by second and third-year males, and finally the female at the bottom. The birds are similarly positioned in profile and against a sparse background to eliminate environmental distractions.

Left: Alexander Wilson’s Orchard Oriole

Right: David Allen Sibley’s Orchard Oriole

Likewise, comparable stylistic tendencies are found in the field guide illustrations of David Allen Sibley (1961-present), a contemporary American ornithologist whose guides are some of the most comprehensive and popular in today’s market. In his depiction of the Orchard Oriole, the adult male, 1st summer male, and adult female are rendered in profile and in close proximity to one another so as to allow the viewer to quickly distinguish the sex and age of the species. Much like Wilson’s engravings, the birds are shown in similar postures that highlight the distinctive markings of the bird. Moreover, the absence of a background or environmental context simplifies the illustration, thus eliminating distractions that might take focus away from identifying the bird.

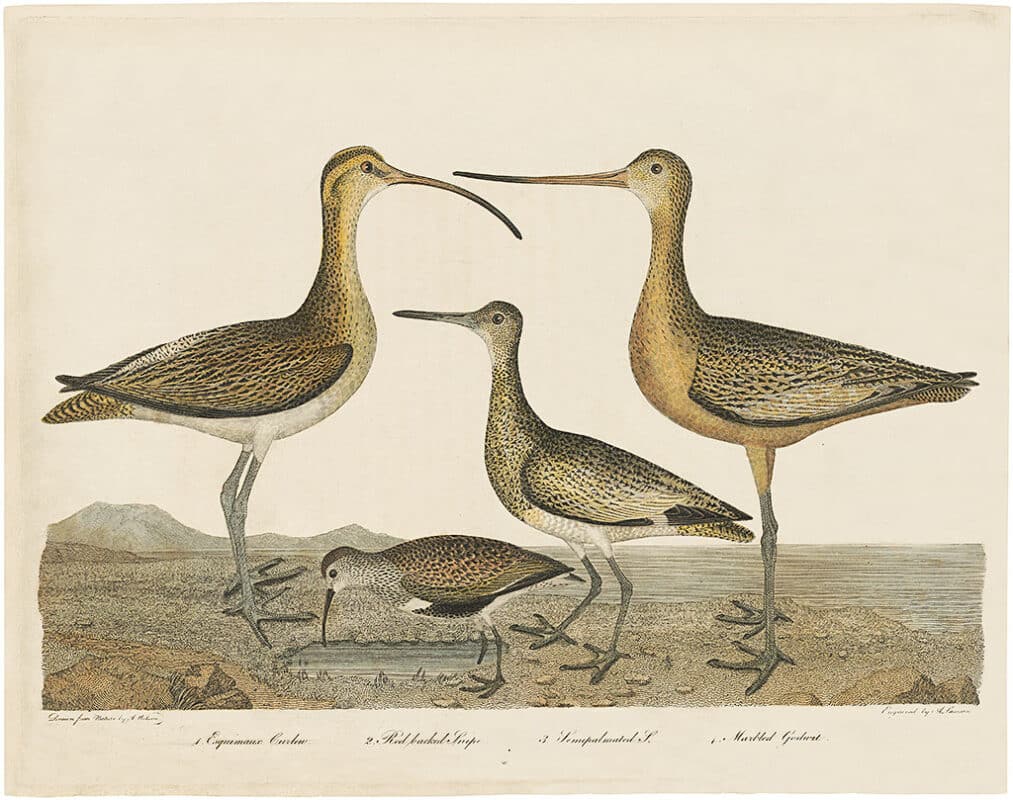

Interspecies Comparison

In contrast to his depiction of a singular species in Pl. 4 Orchard Oriole, Wilson’s Pl. 56 Esquimaux Curlew; Red-backed Snipe; Semipalmated S.; Marbled Godwit depicts several distinct but visually similar species in the same composition. By framing these visually alike shorebirds in one composition, Wilson allows the viewer to distinguish between the species through proximal viewing and to determine the relative shape, size, and coloring of birds that might easily be mistaken for one another. This is a common trait in field guide art which tends to illustrate similar species in sequence or on the same page so that the viewer is able to quickly determine what they are observing in nature without confusing it with another, near-identical species.

This can be seen in Sibley’s illustration of a number of shorebirds including sandpipers, godwits, snipes, and turnstones. The patterned logic of the page fosters the viewer’s ability to quickly differentiate between species that might at first glance appear very similar. By grouping visually analogous birds together in a singular composition, Sibley’s field guide illustrations allow the viewer to see the relative difference in shape, size, color, and patterning between visually related species.

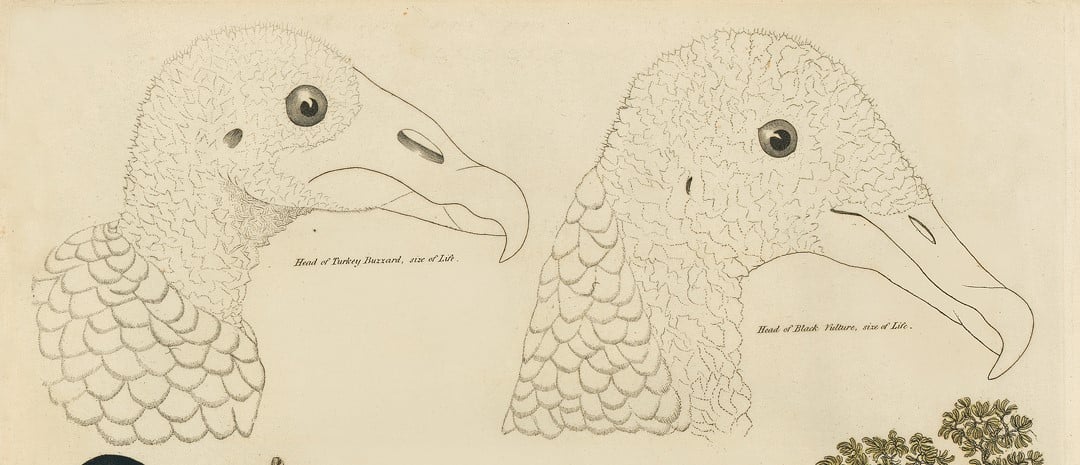

Instructive Diagrams

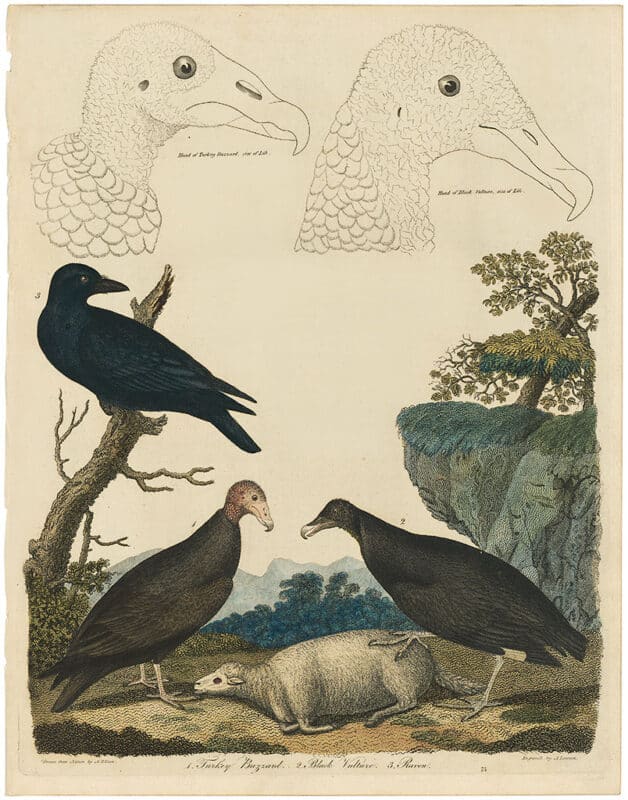

Lastly, Wilson’s artwork occasionally incorporates instructive diagrams that illuminate detailed aspects of the bird. This is evident in Pl. 75 Turkey Buzzard; Black Vulture; Raven in which Wilson includes two black and white line drawings of the carrion bird’s heads. When viewed in the context of the scene unfolding below, the diagrammatic sketches reveal the distinguishing features of the Turkey Buzzard and Black Vulture and indicate their natural size.

Similar ancillary sketches can also be found in 20th-century field guides including those by Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), a foundational contributor to developing the modern field guide blueprint, who likewise employs a diagrammatic feature in his depiction of mergansers. In the top right corner of his composition, a linear sketch is included to punctuate the narrow bill with serrated edges that distinguish the merganser from other diving ducks.

Despite the stylistic similarities between Wilson’s American Ornithology and today’s field guides, a number of distinct differences separate the two. To begin with, while many field guides aim to cater to a broad demographic, Wilson’s folio was prohibitively expensive and “in every sense a luxury commodity” purchased by institutions, scholars, and wealthy individuals at the time of its release (Rigal 1996, 238). Additionally, Wilson’s folio was not often employed as a reference book in the field, but rather it could be found housed in stately libraries and private collections where viewers might ponder the illustrations indoors. Despite these differences, Wilson’s artwork set forth a blueprint that was later adapted and translated to suit the instructional purposes of the modern field guide.

Works Referenced:

Peterson, Roger Tory. 2008. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Rigal, Laura. 1996. “Empire of Birds: Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology.” Huntington Library Quarterly 59, no. 2/3: 233–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/3817668.

Sibley, David Allen. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.