Audubon Prints

A Modernist Approach to Understanding a Selection of Prints from Audubon’s Birds of America

A Discussion of Spatial and Perspectival Distortion, Challenging the Confines of the Print Perimeter, and the Representation of Disembodied Limbs in Audubon’s Art

As an artist-ornithologist of the 19th century, we tend not to place John James Audubon alongside those lauded avant-garde artists of the Modernist movement. While his innovation and contributions to the study of naturalism and printmaking are recognized, we tend to relegate Audubon’s art to the past as reliably realistic and classical. This, however, is somewhat of a reductive assumption because Audubon, in collaboration with his printmakers Robert Havell and Julius Bien, exhibits several traits that are later to become hallmarks of Modernism. These hallmarks include spatial and perspectival distortion, a defiance of the print perimeter, and an embrace of surreal and abstracted forms. This essay will discuss the presence of these traits in several of Audubon’s works including his Bien edition of the Arctic Tern & Sandwich Tern, Havell edition of the Great White Heron, Havell edition of the Black-backed-Gull, and watercolor of the Magnificent Frigatebird.

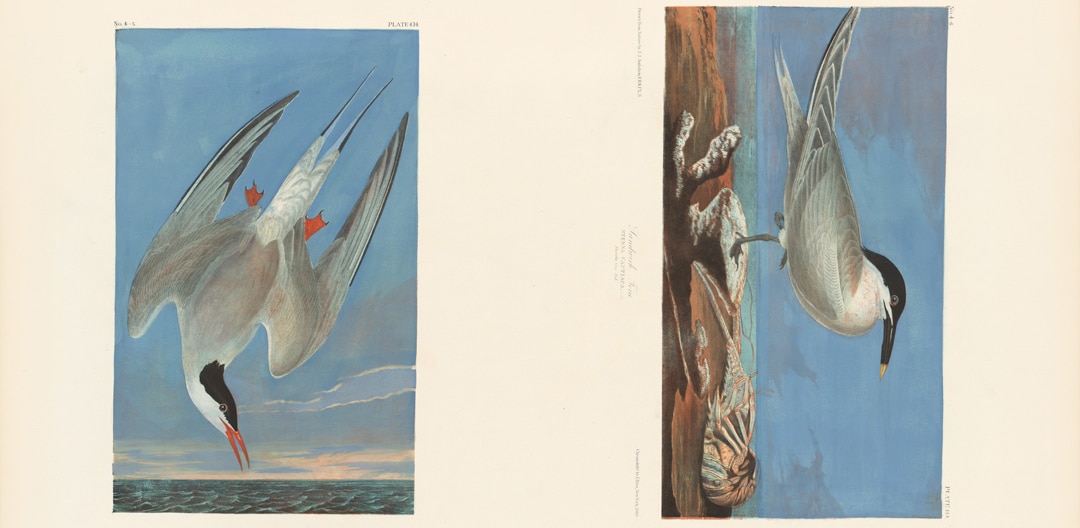

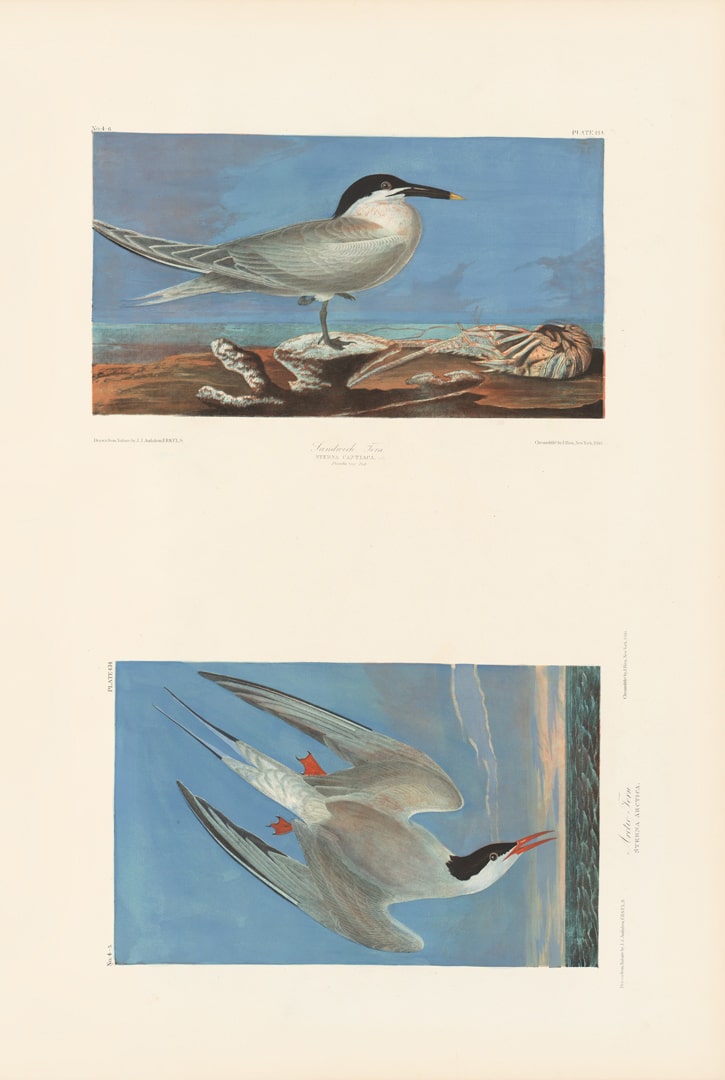

Pl. 434 Arctic Tern & Sandwich Tern

To begin with, Audubon’s Bien Ed. Pl. 434 Arctic Tern & Sandwich Tern is unique in that it displays two parallel plates oriented in antipodal directions. While the Sandwich Tern is right-side-up when the sheet is angled vertically, the Arctic Tern is only right-side-up when the sheet is displayed horizontally. As a result, the work of art could be displayed both horizontally and vertically with both orientations being simultaneously correct and incorrect. This compositional decision was made after Audubon’s death while his son John Woodhouse initiated a reprinting of The Birds of America in 1858 by means of chromolithography. The printmaker employed for this monumental task was the distinguished New York lithographer, Julius Bien. We cannot, therefore, credit Audubon solely for the distinctively modern appearance of this print, and must keep in mind the creative agency of both John Woodhouse and the studio of Julius Bien in rendering this ingenuitive composition.

The Arctic Tern & Sandwich Tern is anomalous among Audubon’s Bien edition prints. While the printing of two plates on one sheet was common and can be seen regularly throughout the edition, the opposing orientations of the two terns is an exceptional compositional decision. While the sheet may have been doubly printed with the intention that the sheet be trimmed, thus separating the two terns, as we can see this bisection did not occur. In fact, the sheet may have been kept whole due to the common practice of housing an edition of prints in a bound folio. By separating these two prints and thus reducing the scale of the sheet, one would therefore disallow them from being bound in a folio with the remainder of the edition. As a result, we are prompted to consider the unique and distinctively Modern treatment of space and perspective in this print through the opposing orientations of the two terns.

Visually, we are greeted with two vibrant blue rectangles occupied by two birds – one static, the other dynamic – causing the composition to read as a study of form, movement, and color. As a result of the distortive orientation of the two birds, the artwork departs from the realm of realism and crosses the border into abstraction.

Audubon Havell Ed. Pl 281, Great White Heron

In addition to his avant-garde usage of space and perspective, Audubon also challenged the confines of the print boundary by allowing the beak of the Great White Heron to break the clearly defined perimeter of the print to enter the sheet margin. Laura Oppenheimer beautifully analyzes the happenstance that prompted this creative decision:

To achieve overall consistency throughout the printed folio and to fit larger birds onto the sheet, Havell made refinements and changes when translating Audubon’s painting into an engraved plate, strictly adhering to Audubon’s dictate that all of the birds be depicted in their actual size. Audubon’s painting of the great white heron covers the paper to the very edge of the sheet. However, for the engraved plate a border was necessary for engraving the title, fascicle and plate numbers, and other pertinent information. In order to accommodate these elements, and fit the great white heron on the sheet in its actual size, which exceeded the rectangle of the plate, Havell allowed the bird’s beak to extend whimsically beyond the edge of the rectangle into the sheet’s border—a dynamic innovation that further animated Audubon’s composition and his portrayal of this avian subject as if it might break free from the two-dimensional plane of the sheet and emerge into three-dimensional space.

By breaking the bounds of the print perimeter and entering “real” space, Audubon’s heron threatens to transgress the normative behavior of art by daring to enter the realm of the viewer. Though not exclusive to Modernism, this motif is one of the fundamental characteristics of the movement.

Havell Ed. Pl. 241, Black-backed-Gull

Much like the heron, Audubon’s Havell Ed. Pl. 241, Black-backed-Gull likewise violates the viewer-object contract by crossing the print perimeter and transgressing into real space. This can be seen to the left of the print where the gull’s open beak breaches the delineated boundary of the print. Likewise, to the right, the gull’s wounded wing tip helplessly flutters out of the print frame. As a result, the gull appears tangible as it advances towards us. Much like the Great White Heron, this creative decision was likely made in order to accommodate the large scale of the gull in its compelling posture.

However, breaking the clearly defined plate perimeter is not the only Modern aspect of this print. In the upper right quadrant of the composition, we are greeted with a disembodied foot, which hovers, with webbed toes splayed, to gesture anonymously downwards at the wounded gull. We can deduce that this autonomous foot is a didactic element of the print and was included so that we may have a more holistic understanding of the gull’s anatomy. However, despite Audubon’s intentions, the print, and more specifically the foot, read as a motif that would not be out of place in a Surrealist painting, (the disembodied nose in Dali’s The Persistence of Memory 1931 comes to mind as a relevant example). While this compositional and instructional device of showing an independent aspect of a bird or flower was not novel in Audubon’s time and has precedent in the artwork of Alexander Wilson and Mark Catesby, it does also curiously relate to the Abstract and Surrealist movements of the 20th century.

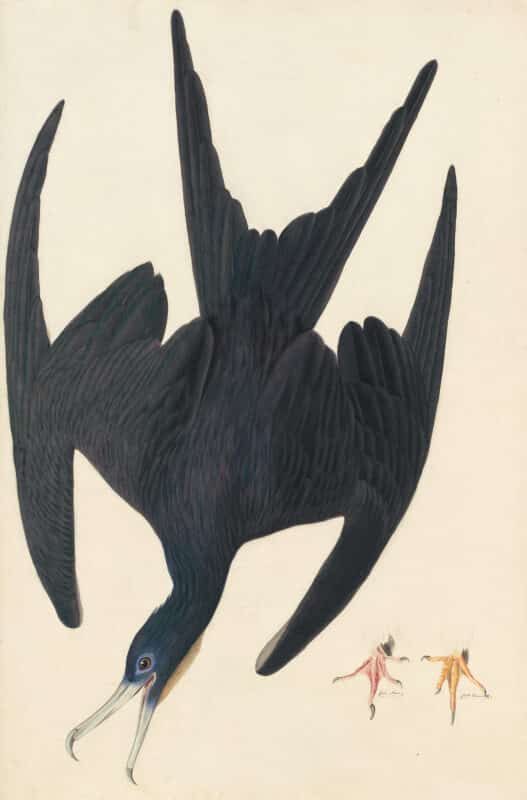

Watercolor of Pl. 271, Magnificent Frigatebird

Lastly, Audubon’s watercolor of Pl. 271, Magnificent Frigatebird, is indeed magnificent in not only its portrayal of the species, but also in its striking form, and, once again, floating appendages. The glossy symmetry of the bird’s form in the composition is disrupted only by the addition of two clawed talons neatly placed near the lower right quadrant, shown in both dorsal and ventral positions. The bird itself is rendered in rich hues of purple, green, and blue, which emphasizes the shape and movement of the creature. The continuous coloring of the bird very nearly abstracts it, presenting it as no more than an aerodynamic shape in space.

The feet, rather than grounding the bird, add to the beauty and oddity of the artwork. Audubon’s inclusion of the feet was a didactic measure used to demonstrate the unique disposition of the frigatebird as a waterbird that does not dive for its prey, but instead skims the water to hook its catch with barbed feet(Ornithological Biography). However, these feet, while informative, create an interesting visual contrast with the agape beak of the frigatebird. The acute angle formed by the bird’s open mouth is echoed in miniature by the two sets of claws that are displayed in a similar manner. As a result, we tend to see the avian subject and its feet as abstract shapes and forms caught in a void. This effect, like that of the Great White Heron’s beak breaking the print perimeter or the perspectival disorientation of the terns, is a fundamental aspect of the Modernist movement that developed long after Audubon’s death.