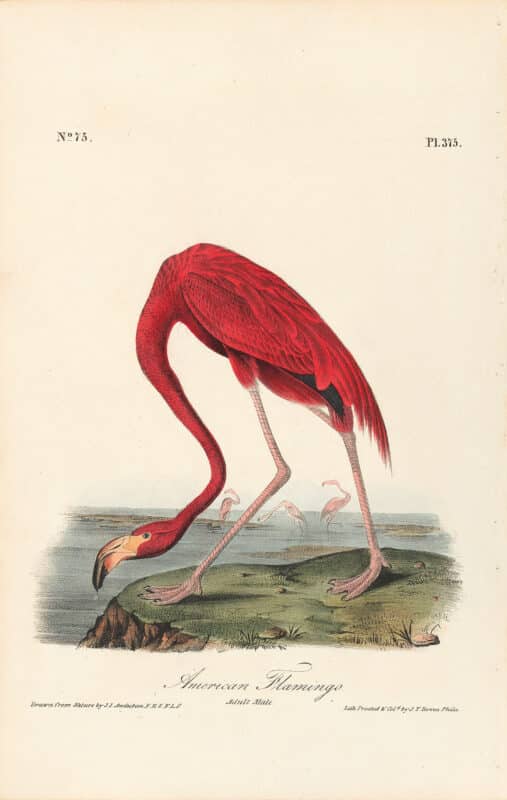

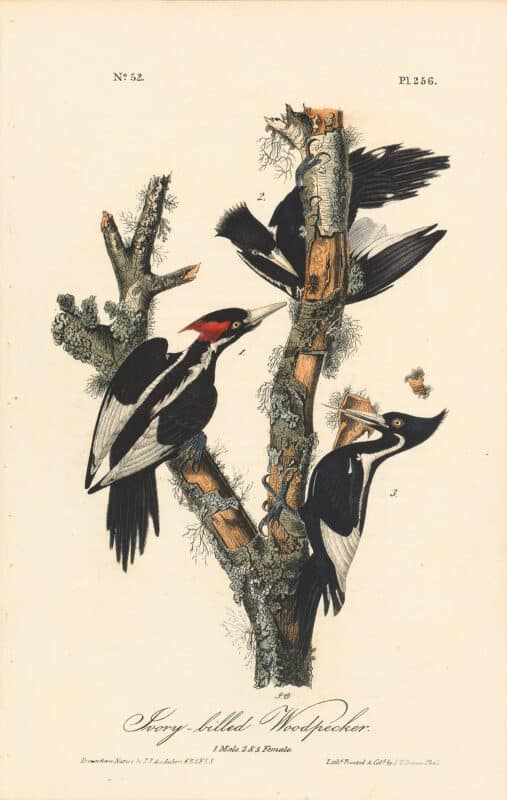

Audubon Prints

Audubon’s Miniature Folio – The Octavo Edition of Birds of America

A survey of the technical translation of Audubon’s work from the monumental to the miniature.

Table of contents

Before the engraver’s ink had fully dried on the last print of Audubon’s Havell Edition of Birds of America, he was already planning a second edition. This edition was to be much smaller than the grand scale of his first, the double-elephant folio (approximately 26 1/2″ x 39 1/2″), and would be printed on royal octavo size paper which measures at 6 ½” x 10 ¼”. The purpose of this octavo edition was to make Audubon’s monumental folio accessible to a broader demographic by reducing its size and associated cost. As a result, the smaller, less costly, and more portable edition was a great success and resulted in the sale of well over 1000 copies internationally. This essay considers the technical translation of Audubon’s work from the double-elephant folio to the octavo edition.

Havell edition Pl. 11 Bird of Washington

38 3/4″ x 25 1/4″

Octavo Pl. 13, Washington Sea Eagle

10 1/4″ x 6 1/2″

From Engraving to Lithography

While Audubon’s Havell Edition was printed through the processes of aquatint-engraving, his octavo edition of Birds of America was lithographed by John T. Bowen in Philadelphia. This change in printing techniques parallels the broader technological developments in printmaking during this time. While etching and engraving cornered the printing market for the first half of the 19th century, developments in lithography compounded by the tail-end of the century making it more attractive to artists and publishers for a number of reasons. Most significantly, lithography was less expensive than etching or engraving, which required costly metal plates and the expertise of highly-trained engravers. Lithography, on the other hand, used stone rather than metal plates, which artists could draw directly onto without mediation resulting in a greater sense of immediacy in the linework.

Review of the Lithographic Process

Developed and refined in the mid to late 19th century, lithography is a planographic process that renders no embossment because the paper and the lithographic stone exist on the same plane. Unlike engraving, which is predominantly a mechanical process by which lines are etched into a matrix, lithography is heavily reliant on chemical reactions. Through the hydrophobic nature of oil, an image is drawn with a waxy crayon or substance onto a stone, which is then treated with gum arabic and acid to etch the grease-based image onto the stone’s surface. Then, when the stone is inked by the printmaker, the ink will only adhere to the areas that have been touched by the waxy crayon. Finally, the prepared stone is run through the press and the image is realized on paper. This process is repeated as many times as there are colors in a print, for each color requires a separate stone bearing the lines and silhouettes of that color exclusively.

Translating the Birds from Monumental to Miniature

As a miniature edition of the previously published Havell prints, Audubon, with the help of his two sons, reduced his prints of the birds to fit on octavo-size paper by means of a camera lucida. George Dollond, the original manufacturer of Sir William Hyde Wollaston’s camera lucida, from Description of the camera lucida, 1830 “Designed by English scientist William Hyde Wollaston in 1807, the camera lucida was nothing more than a carefully positioned glass prism held at eye level by a brass rod over a flat piece of drawing paper. Looking through a peephole centered over the edge of the prism, the artist could see both the object to be drawn and his paper.” (Audubon’s Great National Work: The Royal Octavo Edition of The Birds of America, Ron Tyler, 1993, p. 54) The result of this technology was the ability to trace the referenced image at a smaller scale. John Woodhouse, Audubon’s youngest son, assumed the responsibility of drawing the birds to a reduced scale, while Victor Gifford, Audubon’s eldest son, managed the family’s business affairs pertaining to the production and dissemination of the edition.

Size comparison of the Double-Elephant Folio and Royal Octavo Edition prints

Once the reduced-scale bird drawings were complete, Bowen’s printmakers would then trace the drawings with red or brown pencil, place them face down on the lithography stone, and rub the back of the paper to complete the pigment transfer. This process is elucidated in the two images below of Audubon’s Pl. 462 Tufted Puffin. On the left, we have the tracing of John Woodhouses’ miniature drawing of the puffin penciled on translucent paper with adhesive remnants that would have held the paper steady as the artists worked. Meanwhile, on the right we have the final lithograph of the Tufted Puffin with hand-applied color.

After the image was successfully transferred onto the lithographic stone, it was then refined using a greasy crayon and etched into the stone. Then the stone was inked and the print was pulled, before the final application of color. The colorists, often women, would reference an approved print, Havell edition of the same print, or one of Audubon’s watercolor in order to maintain consistency of tone and hue while coloring. Each colorist attended to a singular color before passing the print on to the next colorist who would then apply their assigned color. Lastly, a “finisher” did what was necessary to complete the overall coloring of the print.

In congruence with the issue of his Havell edition, Audubon likewise issued the octavo edition through subscription basis from 1839 until 1844. However, he rearranged the plates so that like-species were issued together and in phylogenetic order. As mentioned previously, the project was a massive success and Audubon “might have made as much from the octavo edition as from the double elephant folio but in less than half the time” (Audubon’s Great National Work, 103). Published at the height of the American frenzy for “national” works of art, Audubon boasted a diverse array of subscribers from scholars and political personnel, to Louisiana planters and those of the new mercantile class (Audubon’s Great National Work, 102).

What makes the octavo edition remarkable?

Ron Tyler, historian, author, and retired director of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, suggests that “Important factors in the octavo edition’s success were its beauty, comprehensiveness, and authenticity. Audubon had not conceived it or put it together in a year or even a decade; it was the culmination of the work of a lifetime, the fulfillment of his “Great Work” (Audubon’s Great National Work, 3). Along with the printed plates, Audubon included portions of his text -the Ornithological Biography- in the octavo edition. The result is a comprehensive, highly informative work of art that caters to both naturalists and appreciators of art alike. Visually the octavo edition is simplified in order to accommodate the reduced scale of the images. This, in turn, reduces the distraction of environmental elements and thus lends sole focus to the bird depicted. Fostered by its small scale, the octavo edition provides the observer with the opportunity for an intimate encounter with the prints, and encourages the viewer to pour over the detailed imagery with unhurried deliberation.