Audubon Prints, Birds and Animal Art

Audubon’s Havell Edition of the Raven and American Crow

Sensorial engagement and challenging object-viewer relations in Audubon’s prints

As the later days of autumn draw near, many of us may find ourselves disentangling festive cobwebs, closeting the prop skeleton, and packing up a decorative crow or raven along with the rest of our Halloween paraphernalia. So too in John James Audubon’s time, the raven maintained a superstitious mystique because of its dark plumage, foreboding call, and penchant for carrion.

Content

However, Audubon sought to complicate this insular perspective of the raven by highlighting the creature’s intelligence, vigilance, and industrious nature. Likewise, in depicting its cousin, the American crow, Audubon likewise renders the bird as charmingly mischievous, relatable, and in possession of anthropomorphic characteristics. Moreover, both the Raven and the American Crow engage with the viewer in a unique and sensorial way such that the boundaries between object and viewer are blurred.

Audubon Havell Edition Pl. 101, Raven

View ProductLamenting man’s offense against the raven, Audubon declares that “its usefulness is forgotten, his faults are remembered and multiplied by imagination; and whenever he presents himself he is shot at, because from time immemorial ignorance, prejudice, and destructiveness have operated on the mind of man to his detriment” (Audubon 1831, 80-81). In order to combat this negative view of the raven, Audubon casts the bird as majestic and dignified in his print.

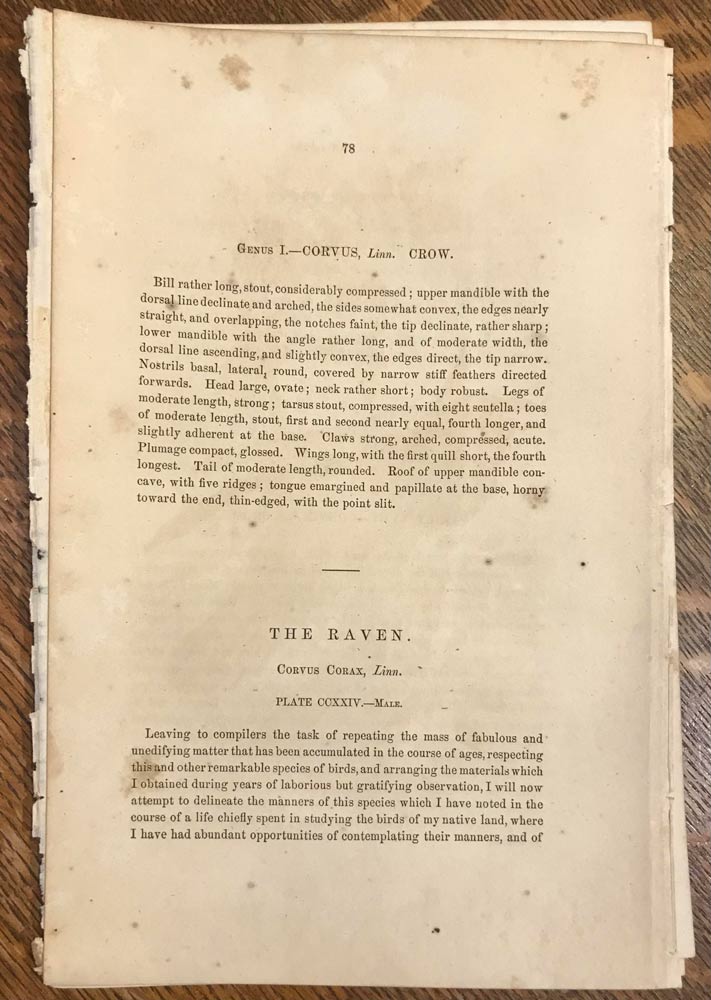

The Raven

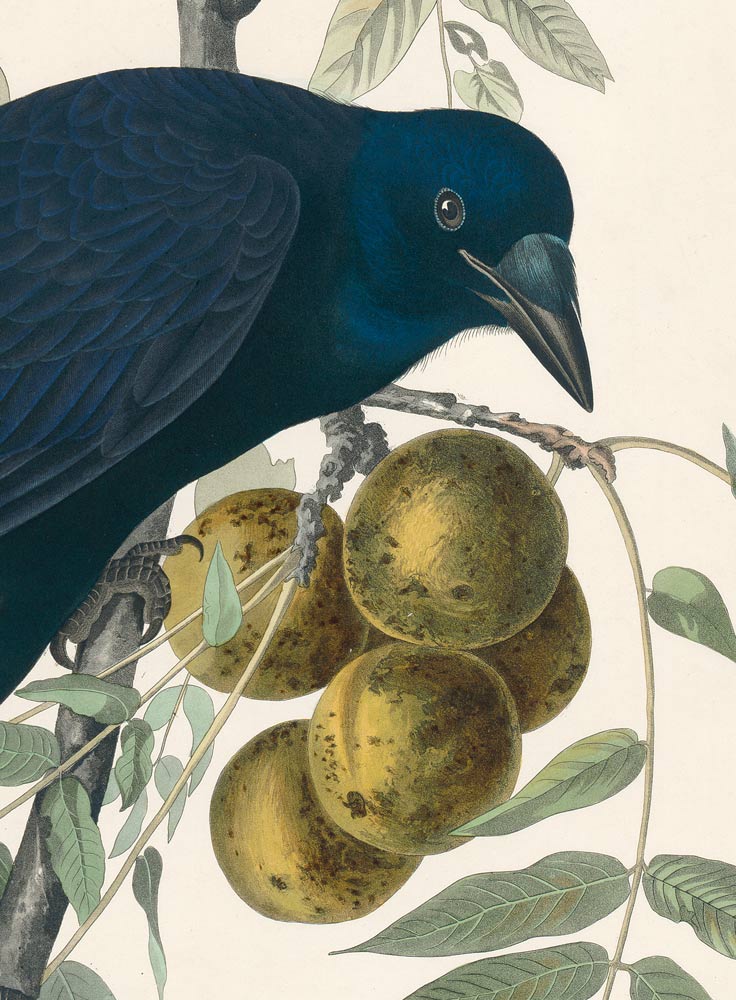

Take for example his Havell edition engraving of the Raven, pl. 111, in which he aggrandizes the bird by lending sole focus to the singular creature. Large and majestic, the bird’s dark plumage lends him a sense of weight and density. And yet he appears agile as his dexterous, anisodactyl claws and shuffling wings actively work to stabilize him on his perch. With his beak ajar, we can imagine a familiar caw issuing from the creature’s throat. Audubon treats this bird in a similar manner to his majestic representations of the Wild Turkey or the Great Blue Heron in which a single bird occupies the entire composition. Rather than depict the raven alongside his companions, amongst whom he is known to congregate, Audubon has chosen to isolate the bird in this print. In doing so, we are confronted by the bird who acknowledges our presence by directly addressing us with his large, unblinking eye, and his vigilant temperament.

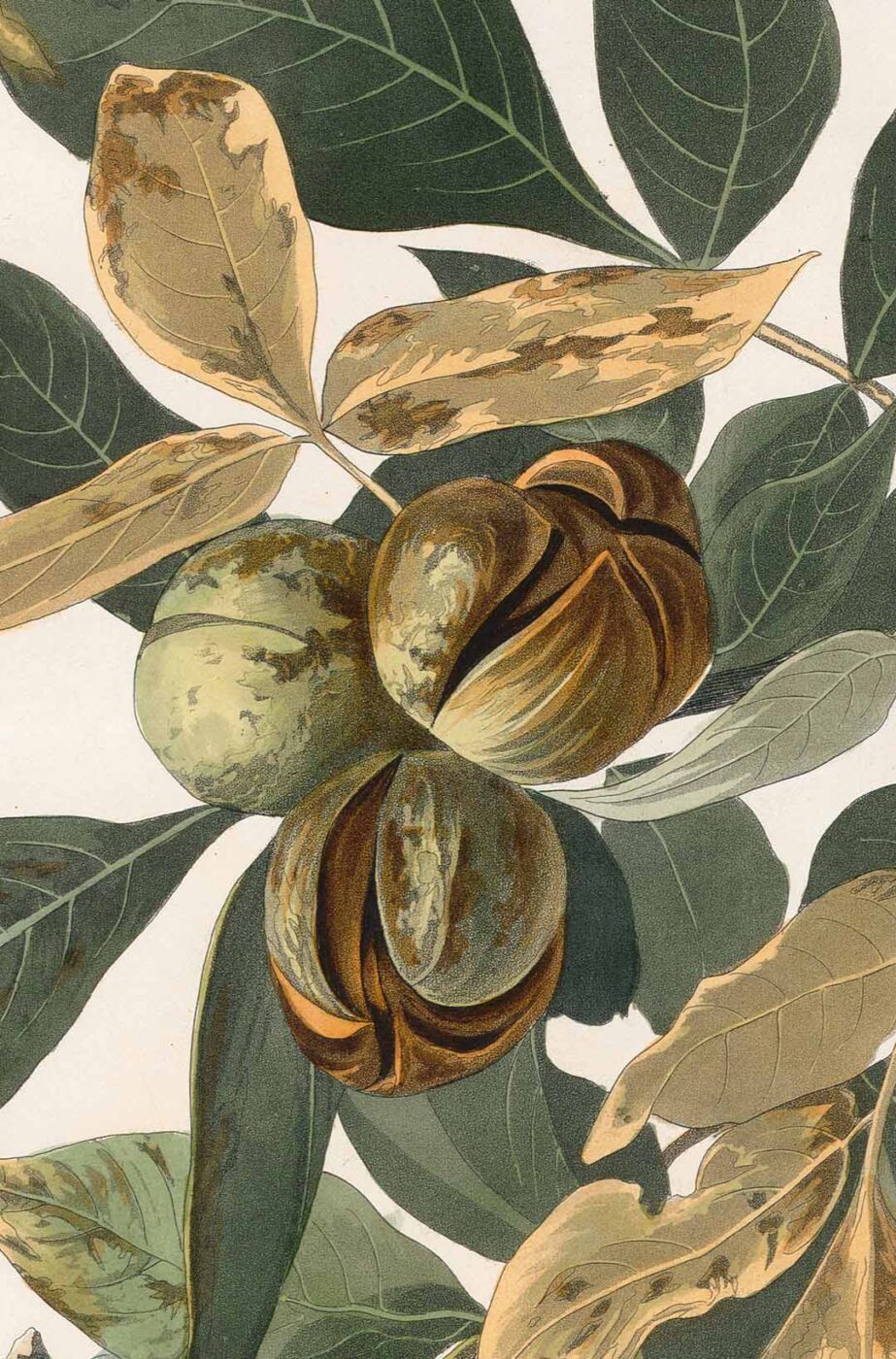

Rendered in subtle tones of blue and iridescent hints of green, the Raven demonstrates “that Audubon knew that simple black does not exist in nature” (Olson 2012, 474). Similarly, the curvature and repetition of the bird’s stratified feathers emphasize the dynamism of his angular body presented in diagonal contrast to the movement of the Hickory tree. The tree itself acts as a pervious backdrop against the solidity of the raven and works to emphasize his stability and grandeur. Drooping from its boughs are large, ripe hickory nuts that burst at their designated seams, and, along with the changing leaves, indicate the closure of fall and the onset of the winter season.

Sensorial Engagement

This print engages our senses on a number of levels by prompting us to conjure our memories of the damp smell of ripening hickory nuts, the crackling sound of brittle leaves underfoot, and the familiar caw of the raven as he heralds the approach of winter. Likewise, this print appears almost tactile due to the contrasting textures presented. We are invited to imagine the feel of the glossy underbelly of the raven, the crisp give of the leaves underfoot, and the satisfying density of the hickory nuts when weighed in our palm.

The American Crow

In a slightly different approach, Audubon humanizes the American Crow, pl. 156, by emphasizing its mischievous qualities and anthropomorphic posture. The crow shuffles his feet with unease and appears startled and displeased by our intrusive presence. He ducks his head as though assessing our capabilities and the nature of our intentions. Like a boxer in the ring, he alternates the weight of his body to his back foot in a defensive stance in order to position himself for a lunging escape or an attack if provoked. Sizing us up, he calculates his next move. Moreover, the crow maintains that unmistakable look of a mischievous child caught with his hand in the cookie jar. In this case, the proverbial cookie jar manifests as a small nest belonging to the Ruby-throated Hummingbird which is located suspiciously close to the crow’s wandering right talon. Audubon observes how “The most remarkable feat of the Crow, is the nicety with which it…pierces an egg with its bill, in order to carry it off, and eat it with security” (Audubon 1831, 89).

In addition to its neighbor’s eggs, the crow also likes to feed on the farmer’s corn crops. Predictably, this earns him a bad reputation and makes him an unwelcome sight in the agricultural arenas. And yet, Audubon points out how the crow is in fact essential to farming because of its impact on reducing mice and insect populations that would otherwise decimate the fields, and infect the flocks. Excerpt from Audubon’s Ornithological Biography, published in 1831He explains how “The Crow devours myriads of grubs every day of the year, that might lay waste the farmer’s fields; it destroys quadrupeds innumerable, every one of which is an enemy to his poultry and his flocks. Why then should the farmer be so ungrateful, when he sees such services rendered to him by a providential friend, as to persecute that friend even to the death?” (Audubon 1831, 88) Audubon implores the farmers to reconsider their intolerance of the crow by enumerating its many virtues. Likewise in his print, Audubon humanizes the crow by highlighting it’s mischievous qualities that are recognizable and familiar to the human viewer.

Questioning Object/Viewer Relations

Much like the sensorial nature of the Raven, so too the American Crow engages with us, but this time by flagrantly overturning normative object/viewer relations. The crow reacts to our presence, and, in doing so, indicates that we too are being watched. His unblinking eye causes us to suddenly become aware that our gaze is being reciprocated. As a result, the reciprocal gaze creates a conduit of mutual consideration between the viewer and the viewed.

In conclusion, Audubon asks us to question the reasons why ravens and crows frequently elicit negative connotations in our cultural system of signs. He accomplishes this by nuancing the negative connotations of the birds, and by instilling them with familiar virtues and relatable tendencies in his prints. Furthermore, Audubon overturns the subject/object relations within American Crow by positioning the bird as an observer of us. As a result, we are challenged on a number of levels to empathize with the creature and to consider the similarities we share with it.