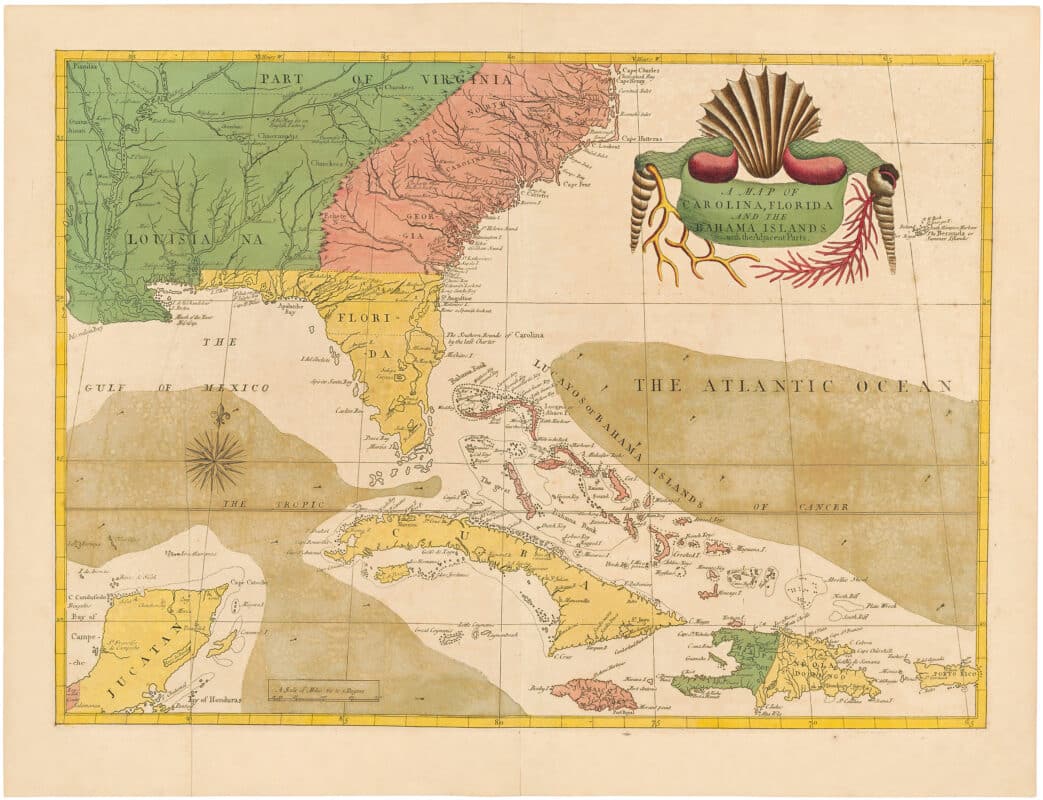

Birds and Animal Art

Catesby’s Crustaceans – Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands

Picturing Oddity and Abundance in British Colonial America

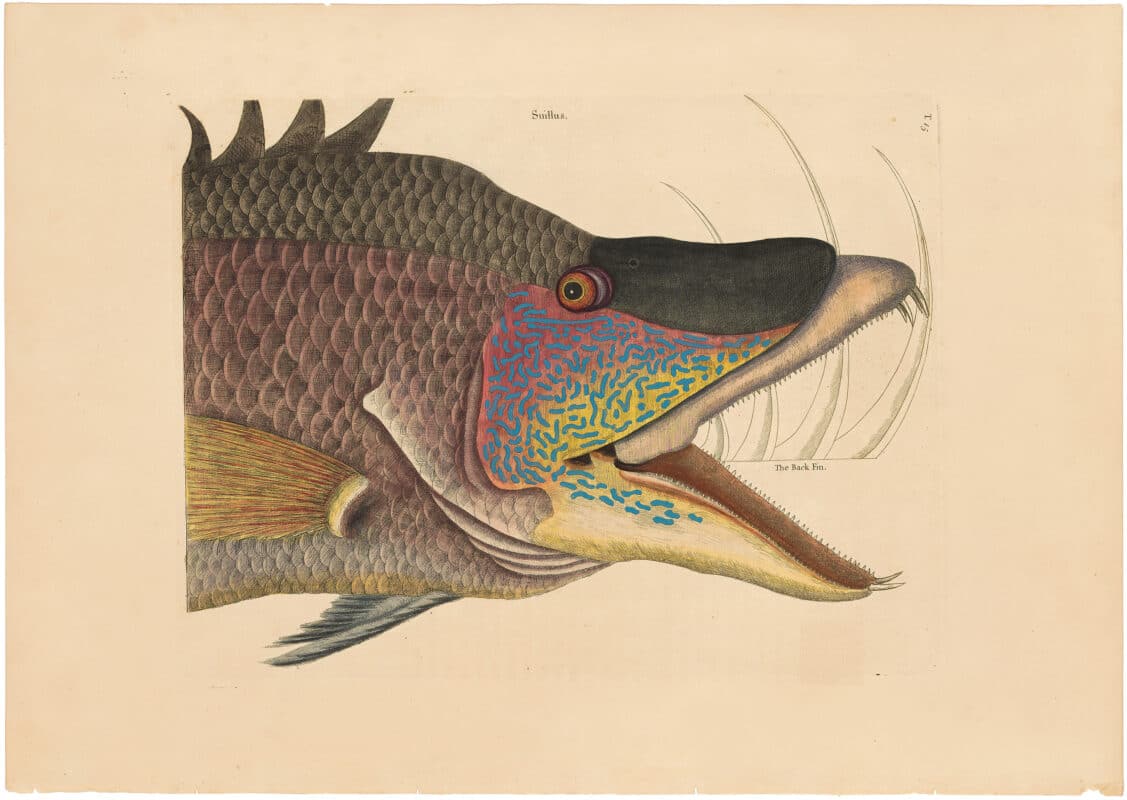

Mark Catesby’s crustaceans, much like the rest of his etchings from his folio Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, possess a medieval charm despite having been produced in Early Modern Europe.

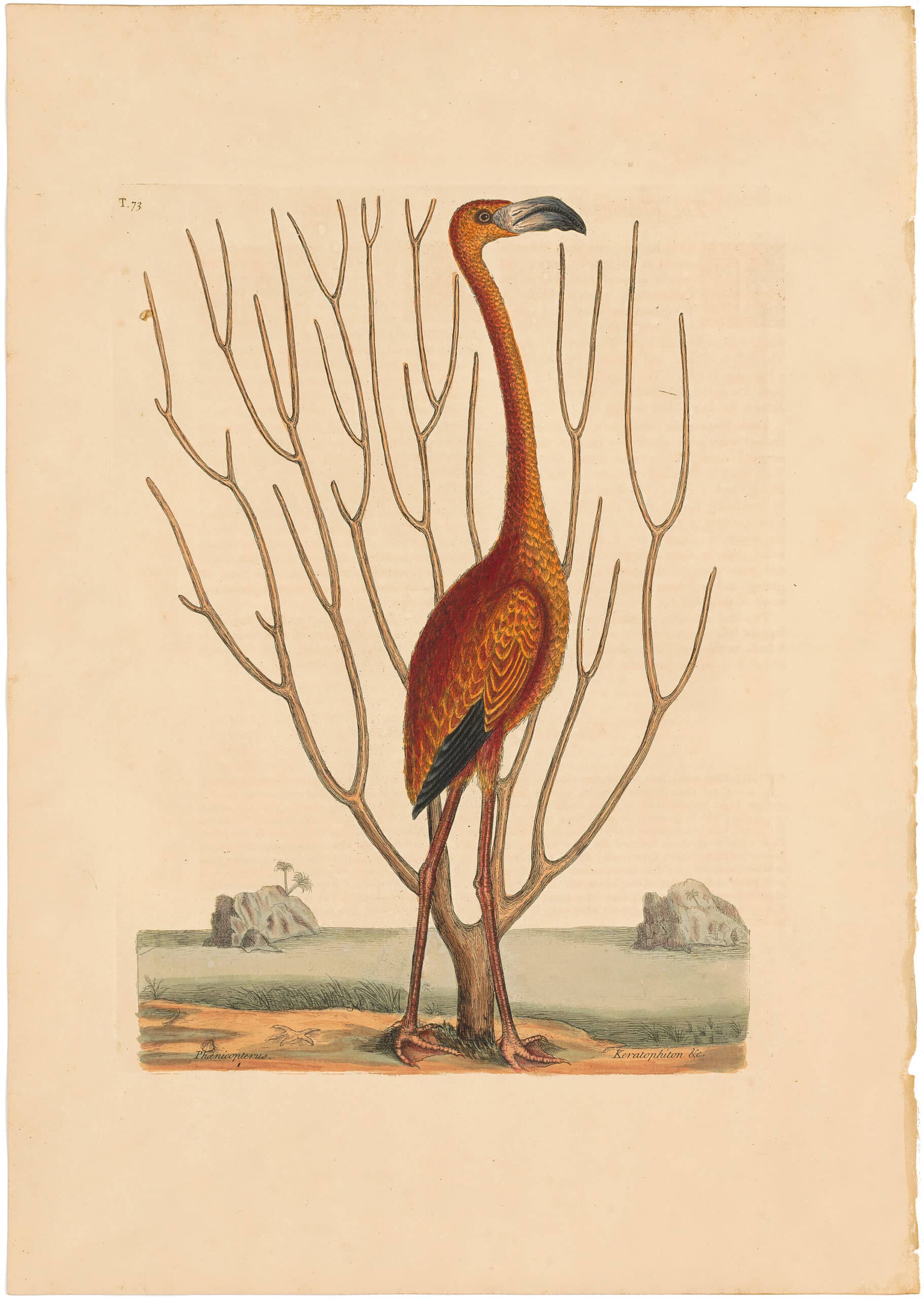

His fish appear endearingly monstrous, his birds adapt anthropomorphic qualities, and his botanical renderings would not seem out of place in the margins of an illuminated manuscript. Likewise, Catesby’s approach to his crabs tests the boundary of realism through his use of morphological manipulation and his playful disavowal of spatial coherence and relative scale. Moreover, Catesby both intonates and obscures the ecological origins of his specimens by decontextualizing them on the page, while simultaneously painting a picture of British colonial America as both strange and alluring.

Catesby’s Background

Born in England in 1683, Catesby produced art in an era in which the framework for natural history was just being defined. As a result, Catesby took the liberties allotted to an undefined discipline by testing the boundary between real and mythological representations. Consequently, his etchings oscillate between being veritable representations, and imaginatively embellished references to nature. Regardless, Catesby’s etchings are charming in their curious approach to zoological and botanical life.

Articulating & Obscuring Environment

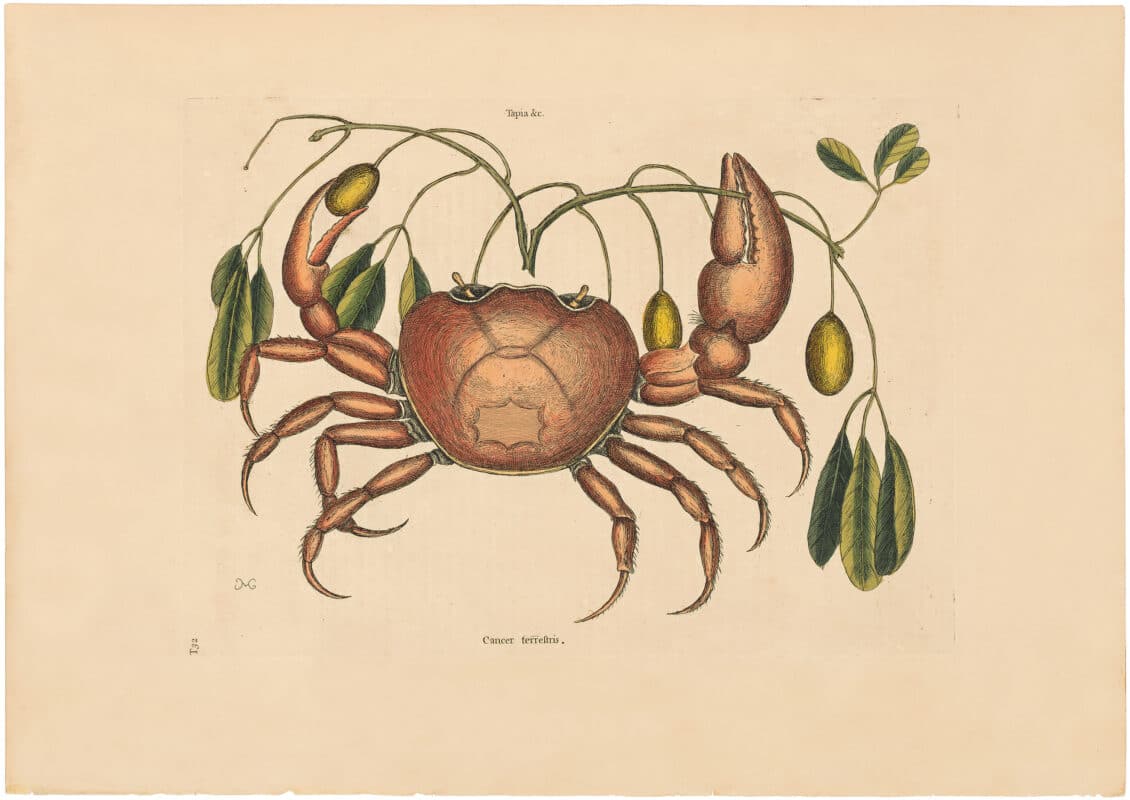

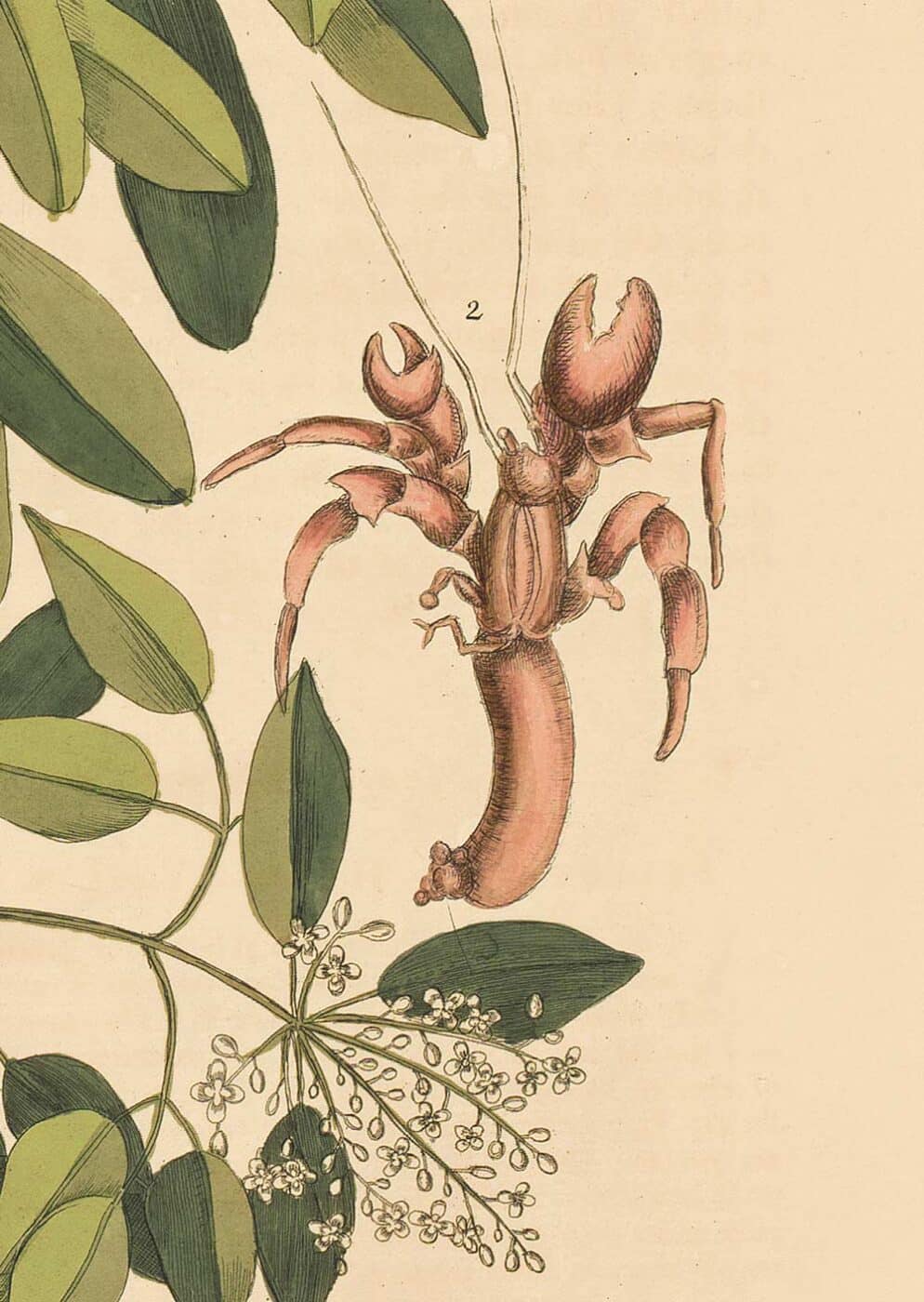

Catesby’s crustaceans, three of which are discussed in this article, are an interesting group of subjects because they synecdochically refer to the larger ecosystem in which they exist. Synecdoche, a literary device in which a part infers the greater whole, can be used to understand Catesby’s schematic approach to these arthropods. Take for example The Land Crab, Pl. 32, in which we are presented with the dorsal view of a crab that holds in its pincers a fruiting Tapia branch, both of which are etched against a blank backdrop. Exiled from their context, we must infer the broader ecosystem in which they exist through the sparse clues we are given. By suspending the specimens against a nebulous background, Catesby invites us, the viewer, to fill in the blank spaces of his etchings with our own narratives.

The fruiting Tapia branch, firmly held in the crab’s pincers, indicates not only the botanical life that substantiates part of the land crab’s habitat, but also the type of sustenance sought out by the species. Referring to the Tapia, Catesby observes that “Of the fruit, amongst many others, these crabs feed” (Catesby, 1771, Pl. 32). We can sense the crab’s intentions through its calculated grasp on the ripe fruit. Likewise, to abet our visualization of the crab’s native terrain and relation to the Tapia twig, Catesby elucidates how “If any [land crab] has a stick in their hand, they will not suffer themselves to be approached so near as without it; and, if walking regardless amongst them without anything in hand, they will approach you with menacing gestures, and, with one of their claws raised, threaten to attack you” (Catesby, 1771, Pl. 32). Not to be trifled with, the militaristic arthropod does not hesitate to weaponize its victuals.

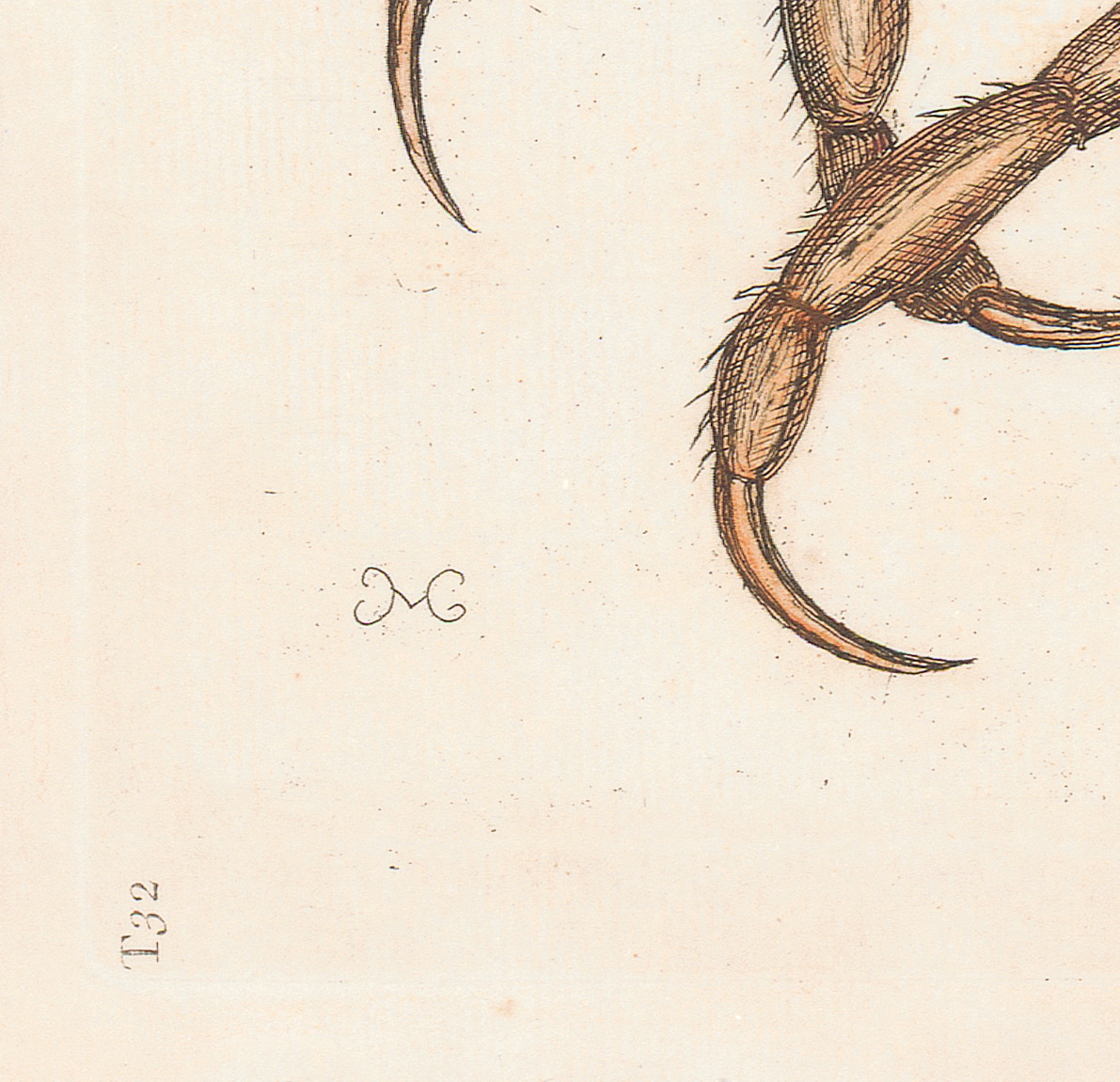

Catesby renders the crab and branch in direct, simplified terms so that we may lend sole focus to the specimens presented to us without being distracted by ambient details. Discrete text at the upper and lower quadrants of the print identifies the land crab, cancer terrestris, and the fruit, Tapia & c, so as to aid our comprehension of the subject. To the lower left portion of the artwork, Catesby has incised his bilaterally-symmetrical monogram; MC.

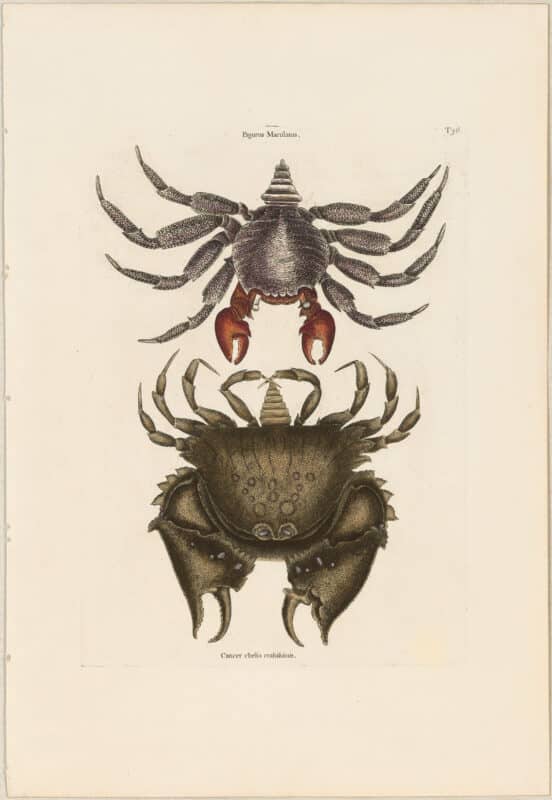

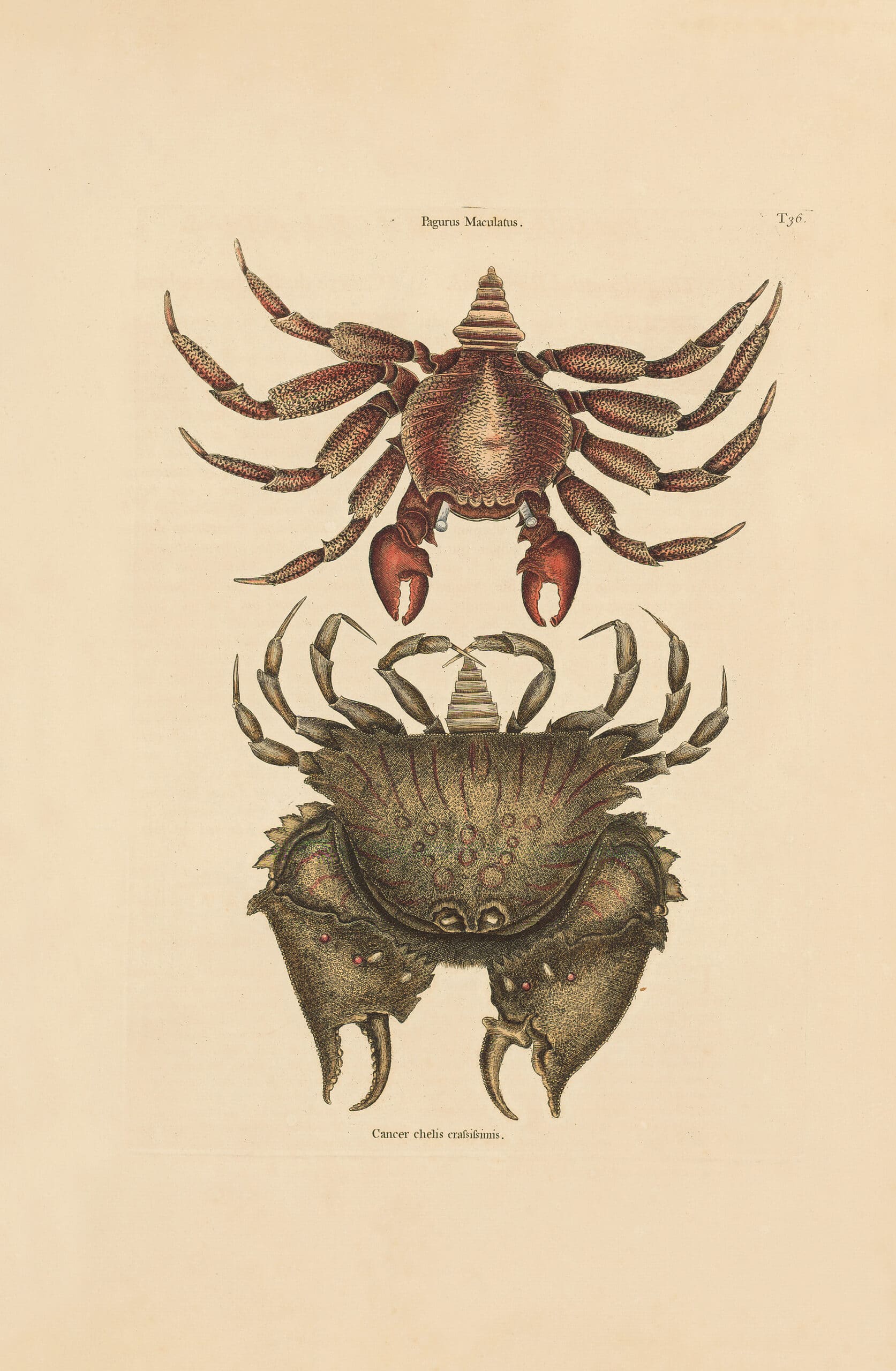

In a similar way, The Red Mottled Rock-Crab, Pl. 36, displays two crabs beautifully aligned in a vertical manner against a blank background. We are once again offered an aerial perspective for optimal viewing cohesion. Catesby’s tapering composition gently guides our gaze from the upturned appendages of the smaller red crab, to the sizable bared chelipeds of the larger sepia crab. The crabs float unmoored on the page, and unlike the Land Crab, they have no additional ecological specimens to suggest their native surroundings.

Cabinet of Curiosities

By extracting the animals and plants from their local environment, and positioning them for optimal viewing, Catesby provides us with an experience not dissimilar to that of a Cabinet of Curiosities. Such cabinets were prevalent in the centuries prior to Catesby but retained popularity well into the 18th century. A Cabinet of Curiosities often contained a panoply of natural objects and artifacts such as animal skeletons, taxidermied birds, fossils, shells, etc. all displayed alongside each other with little intonation of their origin or unique native habitat. Adherence to verity or the implementation of contextual elements was not prioritized in many of these cabinets, rather, the novelty of foreign and strange items was emphasized. Likewise, Catesby’s depictions of isolated natural organisms conjure a similar viewing experience to the cabinet of curiosities. In fact, one of his sponsors, Sir Hans Sloane, acquired a menagerie of over 71,000 items that Catesby had access to. It is likely that the organization of Sloane’s cabinet overtly or subliminally influenced the artist’s stylistic approach to recording animal and plant matter divorced from its native context.

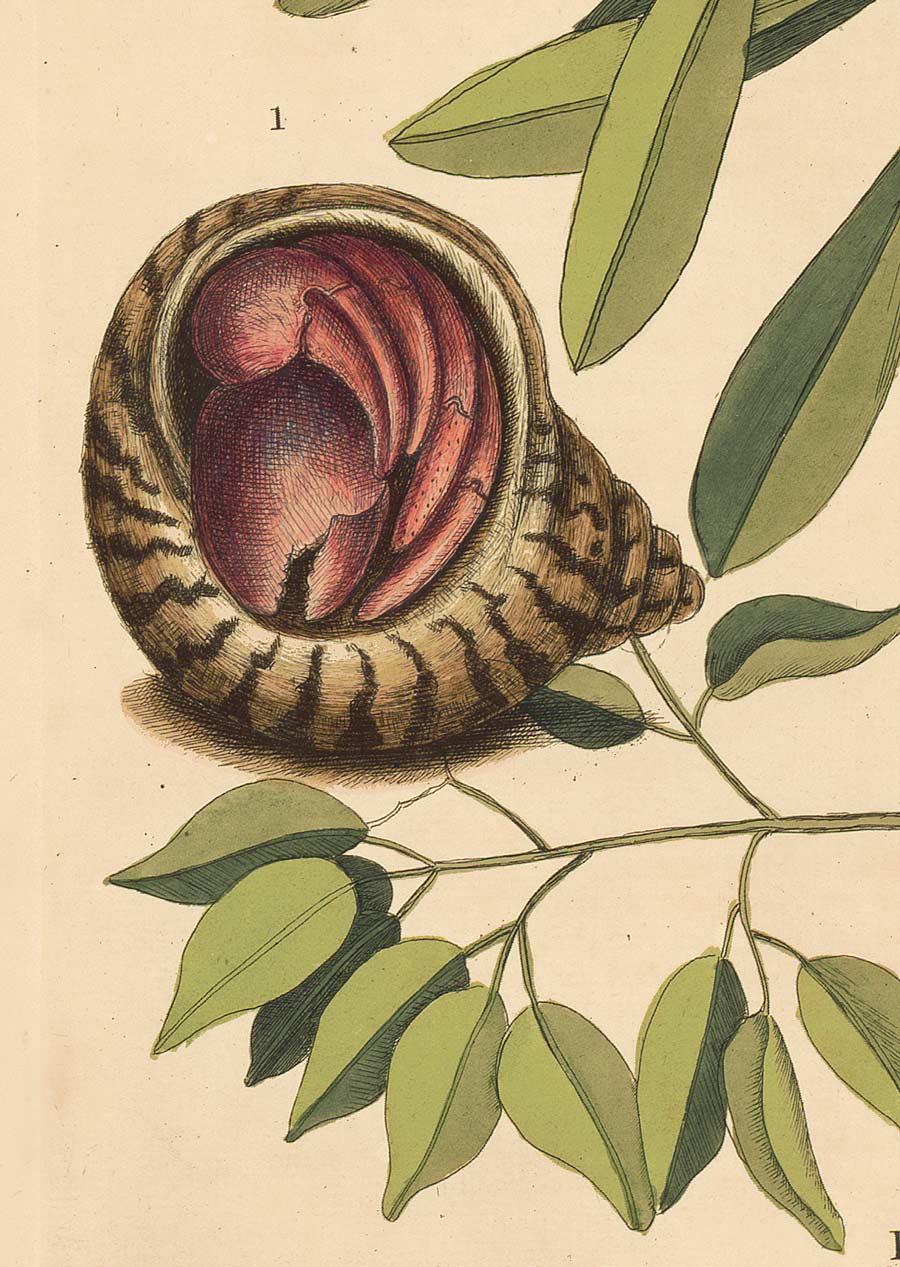

A similar stylistic approach can be seen in The Hermit-Crab, Pl. 33, in which we are offered two perspectives of the creature. One, to the left of the print, provides us with a view of the crab within his shell, one claw protruding to protect the entrance. The other view shows the crab extracted from its shell and laid out in a manner that suggests human intervention. There is no consistent perspectival approach to these crab depictions, rather we are presented with one aerial view and one ground-level view within the same print. Likewise, we get little sense of scale as the two crabs vary in size without explanation as to whether or not they are two perspectives on the same crab or two entirely different crabs. Furthermore, the shell-bearing crab has a slight shadow beneath it while no other specimens in the print share that grounding device.

In fact, the aesthetically truncated sprigs of sea torchwood and button mangrove are manipulated to frame and accentuate the negative space between the two crab specimens. In a similar manner, the shell-less hermit crab’s right legs are bent to accommodate the perimeter of the etching plate. In this way, Catesby’s representations of nature appear to be distinctively manipulated by a human hand. The Hermit-Crab was further manipulated when Catesby translated his field sketch into a print. Due to the nature of etching, Catesby’s print rendered the reverse of the drawing, thus incorrectly switching the dextral and sinistral claws of the crab.

Technical Approach

In fact, etching was a technique that Catesby introduced into his technical repertoire only when faced with the financial difficulties of publishing his folio. Rather than source funds from sponsors, sell the rights to his images, or pay the hefty price of hiring a printmaker, Catesby sought tutelage from Joseph Goupy in order to learn how to etch so as to produce his own prints. These prints were based on his field sketches, which were rendered in pen and ink, graphite, or watercolor. As was popular in his day, Catesby then issued Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands on a subscription basis.

Reception

The contents of Catesby’s etchings were both familiar and, to a degree, unfamiliar to the 18th-century English viewer. After all, this was America, a land yet to be fully surveyed, documented, and tamed by European explorers. For these reasons, Catesby’s playful prints need not follow the normative rules of realism with encyclopedic precision. In fact, by presenting the animal and botanical inhabitants of the Americas as strange and unfamiliar, Catesby catered to the popular sentiment of the time which viewed the British colonies as an unknown wilderness containing exotic and uncharted species.

Simultaneously, however, Catesby’s overall corpus Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, vehemently evokes abundance and plentitude. The sheer number of etchings documenting plants, mammals, birds, and sea inhabitants amounts to over 200 prints. He presents nature as strange, yet enticing, and thus plays into the popular British view of the colonies as both foreign and desirable; reservoirs of bountiful natural resources. Moreover, Catesby’s prints emphasize the animal inhabitants and natural resources of the North American colonies as extractable, and therefore useful to the British colonial enterprise.