Audubon Prints

Discovering Audubon’s Animals in The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

The Imperial Folio

Published between 1845 and 1848, the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America was a collaborative project between John James Audubon, his two sons John Woodhouse and Victor Gifford, and the renowned naturalist Reverend John Bachman. This enterprise runs parallel to Audubon’s former project and magnum opus, the Birds of America, by replicating its structural blueprint.

Table of COntents

Like Birds of America, the Viviparous Quadrupeds was intended to be a comprehensive visual catalogue of North America animalia, with the focus shifting from birds to four-legged land mammals. Accompanying each image, a correlative text was written, primarily by Bachman, to inform the reader of the animal’s habits, diet, habitat, gestation period, etc. Totaling in 150 prints, the project was rushed to completion as Audubon’s health declined. Emerging in the shadow of its big brother Birds of America, The Viviparous Quadrupeds has not received the adequate attention or recognition it deserves.

Background

There has been much speculation as to which aspects of the Quadruped enterprise can be attributed to which of the four constituents. The most common consensus is that Audubon and his youngest son John Woodhouse painted the majority of the animals, while Victor Gifford, Audubon’s eldest son, is responsible for many of the floral backgrounds. John Woodhouse also aided in the production of landscape backgrounds for the prints, while Victor Gifford commanded the sales aspect of the operation by managing the publishing and subscriber acquisition. Rev. John Bachman, on the other hand, focused primarily on the written component of the project, and used his extensive zoological knowledge, coupled with Audubon’s field notes, to construct the informative text published alongside the issuing of the prints.

Dynamic Themes in the Quadrupeds

Anthropomorphizing the Animal

The prints included in the Quadrupeds range from being lively, playful, and warm with a sense of animation and tender relatability, to demonstrating the raw ferocity of nature. Take for instance Pl. 145, Townsend’s Shrew Mole, in which we see three of the oddly shaped creatures moseying about a mossy patch. One has playfully rolled over on its back as though to exhibit its antics to the other, who looks on unamused. Meanwhile, a juvenile Shrew Mole pokes around in the dirt and appears unconcerned with the activity of the elders. This print, like much of Audubon’s work, imbues a human sensibility in the animal subject through tender relatability. The familial dynamic of the trio, as well as the jocose interaction between the mature male and female moles, adds a layer of understanding between the human and animal worlds.

Interspecies Conflict

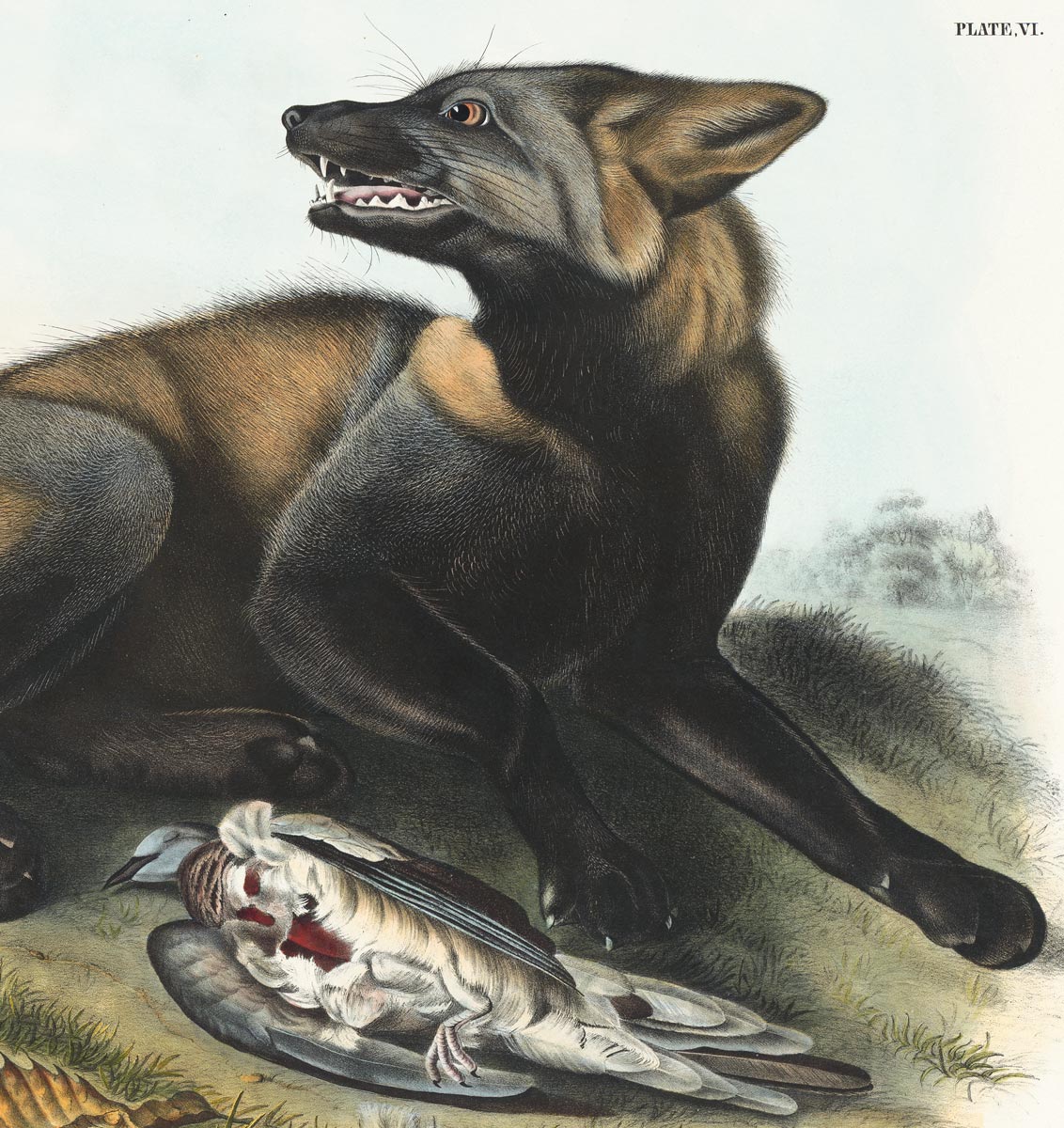

In contrast, the American Cross Fox Pl. 6, and the Tawny Weasel Pl. 148 exemplify the harsher aspects of interspecies relations. In the former print, the fox, having killed a bird, looks up as though in anticipation of an intruder who might interrupt his feathered feast. The wild state of his eyes and the restless movement of his forepaw suggest that he is ill at ease. Likewise, the weasel in Plate 148, lunges at the helpless chicken, and arches its back as it attempts to take her down. Both prints demonstrate a distinctively different perspective of nature than that which was captured in Townsend’s Shrew Mole.

Visualizing the Human Presence

In a similar vein, the Canada Otter Pl. 51 is rife with ferocity and illustrates the harsh reality of the human impact on the natural world. The otter, driven to a state of frenzied madness by the pain of having its forepaw clamped within the iron teeth of the trap, bears its teeth and hisses, making the viewer feel most unwelcome. This print breaks the fourth wall in a unique way that positions us, the viewer, as perpetrator. The reaction of the otter to our presence is accusatory, and we are made to feel guilty for the presence of the man-made trap clamped on the otter’s paw.

Unlike Birds of America, where the human presence and impact on nature is less frequently illustrated, in the Quadrupeds Audubon does not shy away from depicting the cohabitation, conflict, and outright aggression that takes place between the animal and human realms. Native American teepees, farm houses, and other indications of human agricultural development of the land and symbols of domesticity can be found peppering the backgrounds of many of these prints. This distinction between Birds of America and the Quadrupeds may be a result of the collaborative nature of the latter, and the diverse creative energies at play.

Printing the Folio

The Bowen Edition of the Quadrupeds was printed in Philadelphia by lithographer John T. Bowen. Drawn on stone, the prints retain the immediacy of the artist’s hand in a way that is difficult to achieve through intaglio printmaking. In addition, the medium lends itself to the rendering of the soft downy fur, and rough textures of the animal subjects. Lithography, while discovered less than a century prior, progressed greatly in the latter 19th century as innovative artists and printmakers developed its technology. Based on the hydrophobia of oil, lithographs are rendered through the application of a grease-based crayon to a treated lithographic stone which is then inked and run through the printing press. The ink is only retained on the stone where the greasy crayon has left its mark, while all other areas remain unaffected. After being printed on Imperial-sized sheets of paper, the Quadrupeds were then hand painted and issued to the subscribers Victor Gifford had been securing.

At the time of its publishing, the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America was the most comprehensive survey of North American mammals. In 1857 the United States Congress purchased 100 copies of Audubon’s octavo edition of the Viviparous Quadrupeds, as well as another 100 of his Birds of America octavos, “to be presented to foreign governments in return for valuable gifts made to the United States” (The Imperial Collection of Audubon Animals, 1967, Ed. Cahalane, xv). A masterwork of its time, the Viviparous Quadrupeds remain today a work of incredible technical finesse and impressive breadth.