Audubon Prints, Birds and Animal Art

The Evolution of Audubon’s White-headed Eagle

The confluence of creative mechanisms behind Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon’s depictions of the Bald Eagle.

Table of contents

- Wilson’s Eagle

- The First Version of Audubon’s Eagle

- Audubon Reworks his Eagle

- Ornithologists’ Controversy

- Epilogue

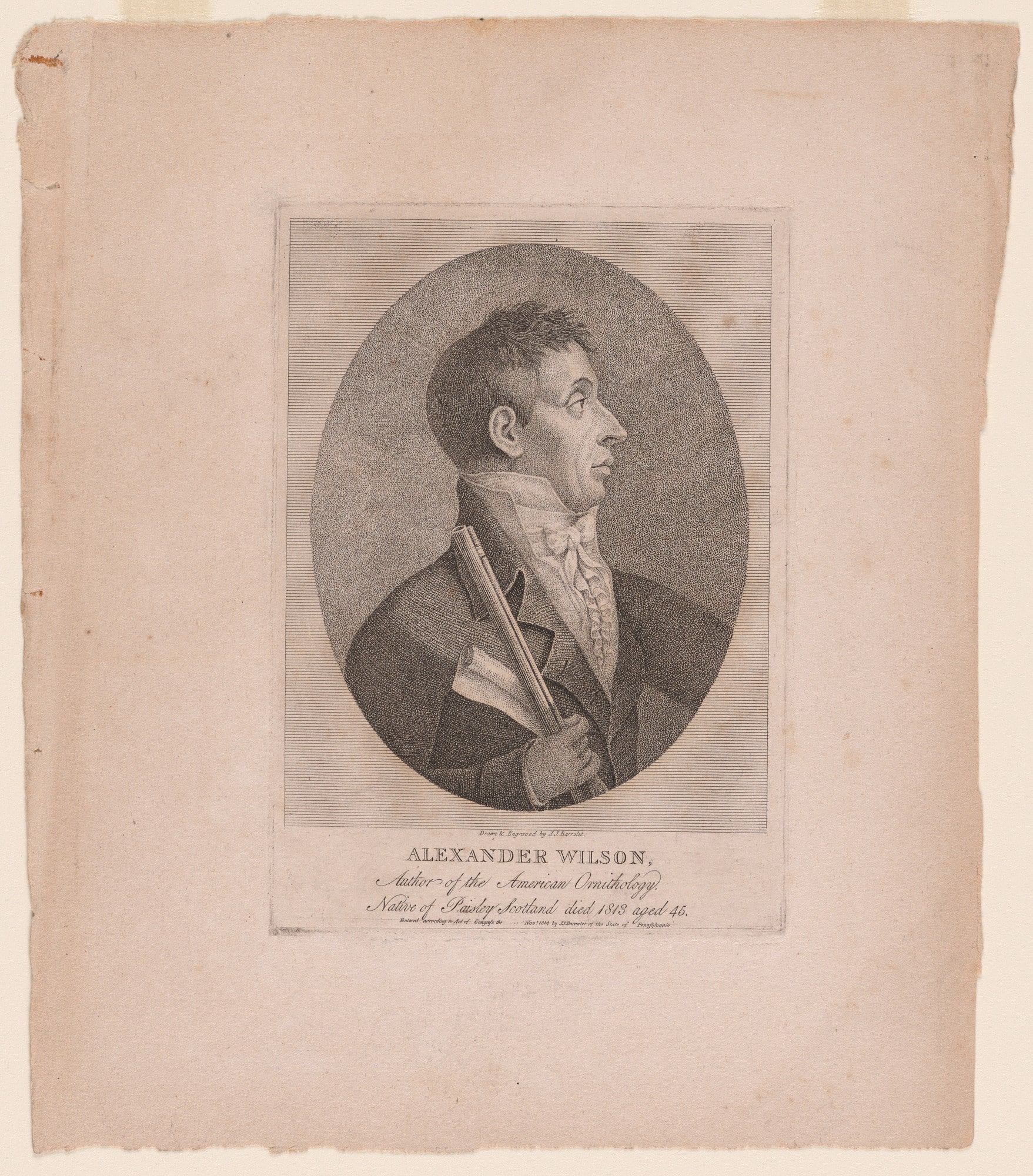

Prior to Audubon’s Birds of America, a Scotsman by the name of Alexander Wilson was the first man to attempt a comprehensive visual survey of North American birds. His crowning work, American Ornithology, predates Audubon’s by over a decade but captures many of the same species that are subsequently depicted by the latter artist. In fact, many scholars suggest that Audubon was directly influenced by Wilson’s methodology, which inspired him to likewise capture the bird life of America in a comprehensive manner. While the two naturalist’s artwork is stylistically and technically very distinct, they do converge on several planes, including their depictions of the White-headed Eagle, (Audubon Pl. 31, Wilson Pl. 36). This artwork demonstrates the confluence of creative mechanisms between Wilson and Audubon’s ornithological projects.

Wilson’s Eagle

Alexander Wilson’s rendition of the White-headed Eagle, Pl. 36, was created in 1810 and issued as part of American Ornithology. In this hand-colored engraving, we are presented with a stern eagle, talons deep in a fish carcass, looking out over a dreamy ravine. A tuft of clouds and a small rainbow decorate the gorge and lend a light-hearted air to the scene.

The First Version of Audubon’s Eagle

Meanwhile, Audubon’s first watercolor rendition of the White-headed Eagle, Pl. 40A, was completed in 1820 and depicts a voracious Bald Eagle dismembering a Canada Goose. Poised near the edge of a craggy cliff beyond which all is sea and sky, the Bald Eagle ruthlessly tears into its downy catch. When viewing this watercolor in relation to Audubon’s 1828 reworking of the subject, shown below, his growth and acumen as an artist become readily apparent. Moreover, Audubon’s respect for Wilson fully materializes in his second rendition of the White-headed Eagle.

Audubon Reworks His Eagle

Completed eight years later, Audubon’s second White-headed Eagle, Pl 31, presents a composition in which he has replaced the goose with a bloated Yellow Catfish. Secured under the relentless talons of the Bald Eagle, the catfish poses a turgid contrast to the sharp angularity and assertive stance of the eagle. The former seascape background of Audubon’s 1820 watercolor has now become increasingly nebulous and abstract, amplifying the dynamism of the composition, and lending sole focus to the activity in the foreground where the carnage of the winged predator’s feast lies strewn on the rocky cliff.

In his journal entry from February 10th, 1828, Audubon makes note of his reworking of this subject:

This morning I took one of my drawings from my portfolio and began to copy it, and intend to finish it better in style. It is the White-headed Eagle which I drew on the Mississippi some years ago, feeding on a wild Goose; now I shall make it breakfast on a Catfish, the drawing of which is also with me, with the marks of the talons of another Eagle, which I disturbed on the banks of that same river, driving him from his prey. I worked from seven this morning until dark

Ornithologist’s Controversy

While Audubon may have been motivated to reproduce his earlier drawing in order to better capture the diet of the eagle or to amplify its visual impact, he “may have also have wished to rework the eagle in order to produce a more convincing image than that of his rival, Alexander Wilson, whose 1812 eagle Audubon had seen when he called on Wilson in Philadelphia”(Slatkin 1993, 161). Several of Audubon’s critics, who happened to be adamant supporters of Wilson, used this print as a means of discrediting his work. Whereas many scholars today agree that Audubon consciously referenced Wilson’s 1812 print in his White-headed Eagle, this holds no bearing on the quality or creativity of the artwork but merely elucidates the complex layers of influence that permeate the generation of any work of art.

In her chapter “The Artist as Entrepreneur,” from the publication John James Audubon: The Watercolors for Birds of America, Annette Blaugrund asserts that “Most certainly Audubon was influenced by the ornithological publications of…Alexander Wilson (1766-1813) in his decision to publish a comprehensive illustrated book of North American birds” (Blaugrund 1993, 28). It is no secret that the substance and breadth of Audubon’s Birds of America and Wilson’s American Ornithology are congruous, and a record of their first interaction in March, 1810, elucidates the nexus of inspiration for Audubon to attempt a similar project. While working in a store in Louisville, Kentucky, Audubon first met Wilson who was actively searching for subscribers to his illustrated survey. Blaugrund suggests that for Audubon “The encounter planted the seed of the idea of publishing his own drawings” (Blaugrund 1993, 29).

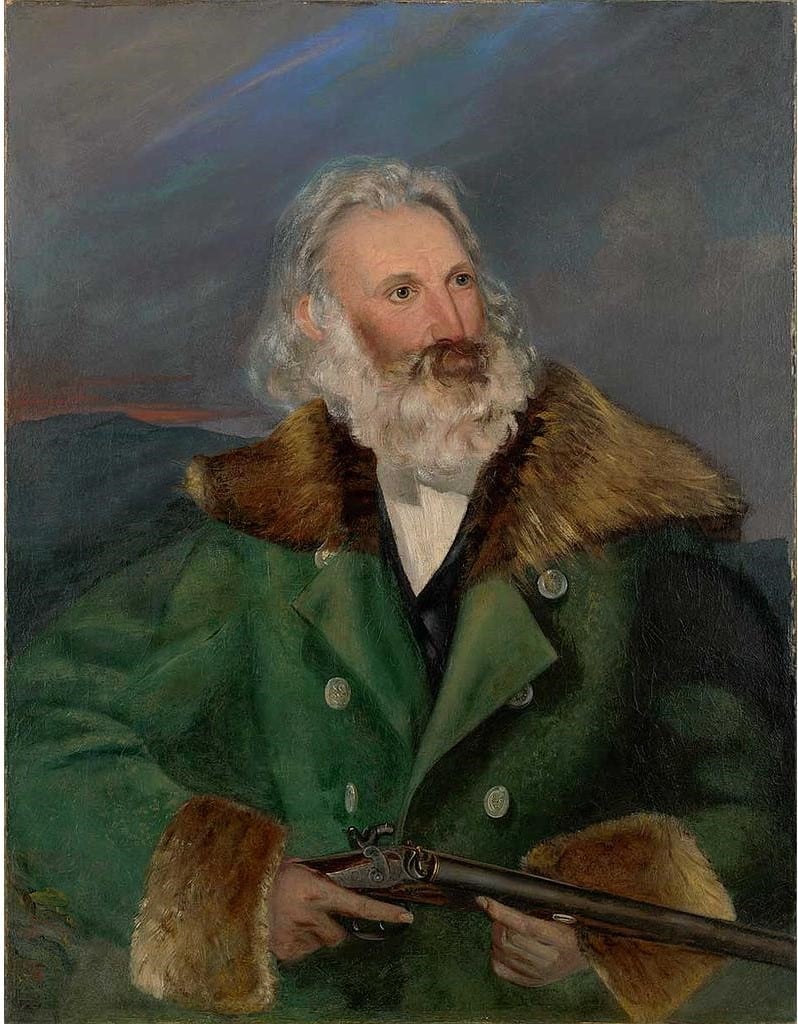

Portrait of J.J. Audubon

Audubon’s Watercolors, John Woodhouse Audubon

Portrait of Alexander Wilson

JJ Barralet, 1814

Additionally, in discussing Audubon’s two watercolors of the White-headed Eagle, Carole Anna Slatkin suggests that “both versions evidently related to, and intended to surpass, Alexander Wilson’s 1812 image of the Bald Eagle” (Slatkin 1993, 108). From his journal entries we know that Audubon held Wilson in high regard, and was saddened when the Scotsman rejected his attempts at friendship or professional collaboration. He ponders: “How pleasing it would have been to me, to have met him on such an excursion, and, after procuring a few of his own birds, to have listened to him as he would speak of a thousand interesting facts connected with his favorite science and my ever pleasing pursuits. But alas! Wilson was with me only a few times, and then nothing worthy of his attention was procured” (Burns 1908, 11-12).

Significantly, one of the few times that Audubon and Wilson were in each other’s company was at the Peale Museum in Philadelphia, where “Audubon found Wilson drawing a White-headed Eagle…using as a model the popular display of a stuffed bald eagle perched on a stone with a catch of fish under one foot” (Rhodes 2003, 93). According to Richard Rhodes, it is this taxidermy model of the Bald Eagle that inspired not only Wilson but also Audubon in his rendering of the subject. This is not to deny Audubon’s admiration of Wilson indicated through his latter reworking of the White-headed Eagle, but merely to pacify any notions of mere imitation in his work. In conclusion, the White-headed Eagle presents a point of connection between the two artists’ oeuvres and illustrates not only the admiration Audubon held for Wilson but also memorializes the two artist’s interaction at the Peale Museum where they encountered the same source material for their respective compositions.

Epilogue

The evolution of the White-headed Eagle, however, outlives both Audubon and Wilson through the work of printmaker Julius Bien. Initially hired by Audubon’s sons to print a lithographic edition of Birds of America, Julius Bien took creative liberties with his execution of the White-headed Eagle. In the Bien edition, Pl. 14, the background of the print is developed and romanticized to suit the preferences of the time. Joel Oppenheimer explains “Bien enhanced numerous backgrounds, adding such romantic elements as a sunset in Pl. 269, Pinnated Grouse, or replacing grassland with a lake in his rendition of Plate 14, Audubon’s White-headed Eagle” (Oppenheimer 2013, 46).

Later Bien would print his own interpretation of the Bald Eagle that demonstrated his American patriotism and allegorizes the turmoil of the Civil War. As an immigrant driven from his German homeland by political unrest, Bien greatly treasured the values and opportunities he encountered in America. This perspective is overtly portrayed in his chromolithograph of the White-headed Eagle, 1861, in which a Bald Eagle, the symbol of the Nation’s embrace of liberty and freedom, is assertively staged over an assemblage of symbolic objects. The American flag, Constitution, and Union shield are among the emblems secured beneath the eagle’s talons. In addition, broken chains, swords, cannon balls, and other symbols of the Civil War and the war against slavery are indicated through the items delineated in the pile. Bien’s allegorical print intertwines the political and social history of America during the 1860s with the Natural History provenance of the image.