Audubon Prints, Birds and Animal Art

Casualties of Fashion: The Contentious History of Plume Plundering

Though the idea of adorning oneself with a bird carcass may seem a bit foreign today, historically, birds and their feathers have played a major and contentious role in self-adornment.

Table of Contents

- A History of Feathered Fashion

- Plume Hunting and Bird Exploitation

- Changing Fashions and the Development of the National Audubon Society

- The Feather Industry Today

A History of Feathered Fashion

With vestiary roots in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the ostentatious plumes of herons, peacocks, and ostriches were often donned by noblemen as symbols of their rank and authority. Frequently worn at tournaments and jousts, feathers were the territory of the ruling classes with sumptuary laws reserving such accessories for the elite (Doughty 1972, 4). Fueled by political expansion and the conquest of new territories, the market for exotic feathers thrived as new and unfamiliar bird species were introduced to European shores. These exotic commodities boasted not only the power and reach of the wearer but also his or her cultural connectedness.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, feathers were largely relegated to the domain of female fashion, and, perhaps ironically, military regalia. With the commercial capacity afforded by the industrial revolution, the popularization of feathered adornments permeated women’s fashion with favored plumes including those of the birds of paradise, herons, gulls, terns, parrots, and the coveted snowy egret whose plumes were worth twice their weight in gold by 1900 (Job 1905, 146). This meteoric rise in feathered fashion was, unfortunately, supplied by the rampant and unregulated hunting of numerous bird species.

Portrait of Gundakar, Prince of Dietrichstein by Jan Thomas van Leperen, 1667. Kunsthistorisches Museum Collection.

Feathers were often worn by nobility to signify wealth, power, and status.

Bird of Paradise Hat, Harper’s Bazaar

The What Women Are Wearing section of the New York Times on September 25th, 1904 indicates how women in the fashion capitals were wearing birds of paradise plumes.

Plume Hunting and Bird Exploitation

At the height of the feather trade between 1870 and 1920, two of the groups most devastated by the plume industry were the snowy egret and their larger counterpart the great egret. Writing for Smithsonian Magazine, William Souder explains how “The egrets’ brilliant white plumage, especially the gossamer wisps of feather that became more prominent during mating season, was in high demand among milliners” as women began wearing hats adorned with feathers, wings, and even entire taxidermied birds (Souder 2013). Taken from rookeries and slaughtered for their mating plumes, the snowy egret population was dangerously diminished and the death of a single adult bird during this critical season condemned the abandoned nestlings to starvation.

Audubon’s Watercolors Pl. 30A, Great Egret

Great and Snowy Egrets were poached for their nuptial plumes which were worth more than their weight in gold by the late 19th century.

view product

Chaumet aigrette, circa 1910

Coming from the French word for egret, the aigrette refers to a headdress adorned with a white egret’s feathers.

Only half a century prior when 19th-century artist John James Audubon observed the snowy egret in the wild, he commented on the abundant population:

“I have visited some of their breeding grounds where several hundred pairs were to be seen, and several nests were placed on the branches of the same bush, so low at times that I could easily see into them” (Audubon 1831, 606).

However, mere decades later, many bird populations were severely endangered and a few, including the Carolina parrot and passenger pigeon, were needlessly driven to extinction.

The Woman Behind the Gun, Gordon Ross, 1911. The Library of Congress.

Illustration shows a woman, possibly Coco Chanel, wearing a large hat with feathers, shooting at large white birds with a rifle; two dogs labeled “French Milliner” place the dead birds on a pile at her feet.

Much of the blame for reckless feather consumption was placed on the millinery industry and female consumers of feathered fashion. Writing to the Museums Victoria in 1865, ornithologist and artist John Gould complained that he was hard-pressed to fulfill a specimen request because

“The Ladies, the Ladies, have however, so stripped us of birds for their bonnets that but few are now in the market and these of course are high priced.”

Similarly, while walking through uptown New York in 1886, Frank Chapman, curator of ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History, noted that over 75% of the 700 hats he counted were decorated with bird parts or the entire bird itself. He identified forty species native to the state but said that in most cases “mutilation rendered identification impossible.” (Chapman). His account was published in an early conservationist magazine, Forest and Stream, and indicates a growing concern for the destructive feather industry.

Accessory set, including muff and tippet, made of Herring Gulls, 1880–99. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection, Image courtesy New-York Historical Society.

In many cases, the entire bird was used as an accessory.

Changing Fashions and the Development of the National Audubon Society

“While women were loudly condemned for their role in consuming feathers, they were also instrumental in raising awareness of the issue.” (Webster and Steele)

In retaliation to the atrocities of the plume trade, nearly 1,000 women led by Boston socialite Harriet Hemenway and her cousin Minna Hall boycotted feathered fashion and sought to promote awareness about wildlife conservation efforts. Their boycott of the feather trade culminated in the formation of the National Audubon Society and set the foundation for the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, which prohibited the hunting of protected migratory bird species and forbade interstate bird transport.

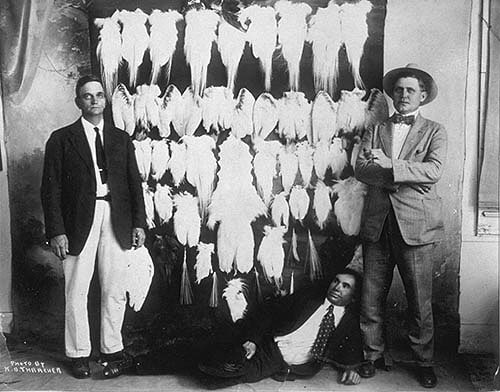

US federal agents with confiscated egret skins, 1930s. Photograph by H.B. Thrasher, David Hall.

After the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, the hunting and interstate transport of protected migratory bird species was outlawed.

As a result of the budding conservationist movement and increased awareness about the dire consequences of the plume trade, public demand shifted in favor of bird-free alternatives such as the “Audobonnet,” a bonnet named after the 19th-century artist-naturalist and decorated with birdless silk and ribbon substitutes. Likewise, many previously endangered bird populations were able to recover but not without the loss of several species including the Carolina Parrot, North America’s only native parrot.

Audubon Bien Edition Pl. 405, Eider Duck

Eiderdown can be sourced from the duck’s nest without harm to the bird.

View ProductThe Feather Industry Today

Feathers continue to be used in fashion today, though the industry is often under pressure to uphold ethical and sustainable sourcing procedures. For example, eiderdown, which has unparalleled insulating properties, can be sourced from the nests of Common Eider ducks with minimal disturbance to the bird. In an effort to keep their eggs warm, female Eiders pluck the downy feathers from their chest and use them to insulate their incubating eggs. The eiderdown can then be gathered from the nest and used for garments and textiles without harm.

Works Cited

Audubon, John James. 1831. Ornithological Biography. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black.

Chapman, Frank. 1886. Forest and Stream: A Journal of Outdoor Life, Travel, Nature Study, Shooting.

Doughty, Robin W. 1972. “Concern for Fashionable Feathers.” Forest History Newsletter 16, no. 2: 4–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/4004150.

Gould, John. Letter dated 20 December 1865, in Museums Victoria Archives, MV ARCHIVES – NATIONAL MUSEUM OF VICTORIA – Inwards Correspondence – 1863-1876 Gould, J., OLDERSYSTEM~02618.

Job, Herbert. 1905. Wild Wings: Adventures of a Camera-Hunter Among the Larger Wild Birds of North America on Sea and Land. Boston Houghton: Mifflin & Company.

Souder, William. March 2013. “How Two Women Ended the Deadly Feather Trade” Smithsonian Magazine.

Steele, Gemma and Hayley Webster. “Flight of fashion: when feathers were worth twice their weight in gold” Museums Victoria.

Audubon's Watercolors - The New-York Historical Society Edition

New-York Historical Society - Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print | circa 2006 | 29.625 x 21.25 inches

Audubon's Watercolors - The New-York Historical Society Edition

New-York Historical Society - Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print | circa 2006 | 29.375 x 21.375 inches

Audubon's Watercolors - The New-York Historical Society Edition

New-York Historical Society - Oppenheimer Editions Fine Art Print | circa 2006 | 37.375 x 25.5 inches