Information

What is a Lithograph? A Practical Guide to Understanding and Identifying Lithographic Prints

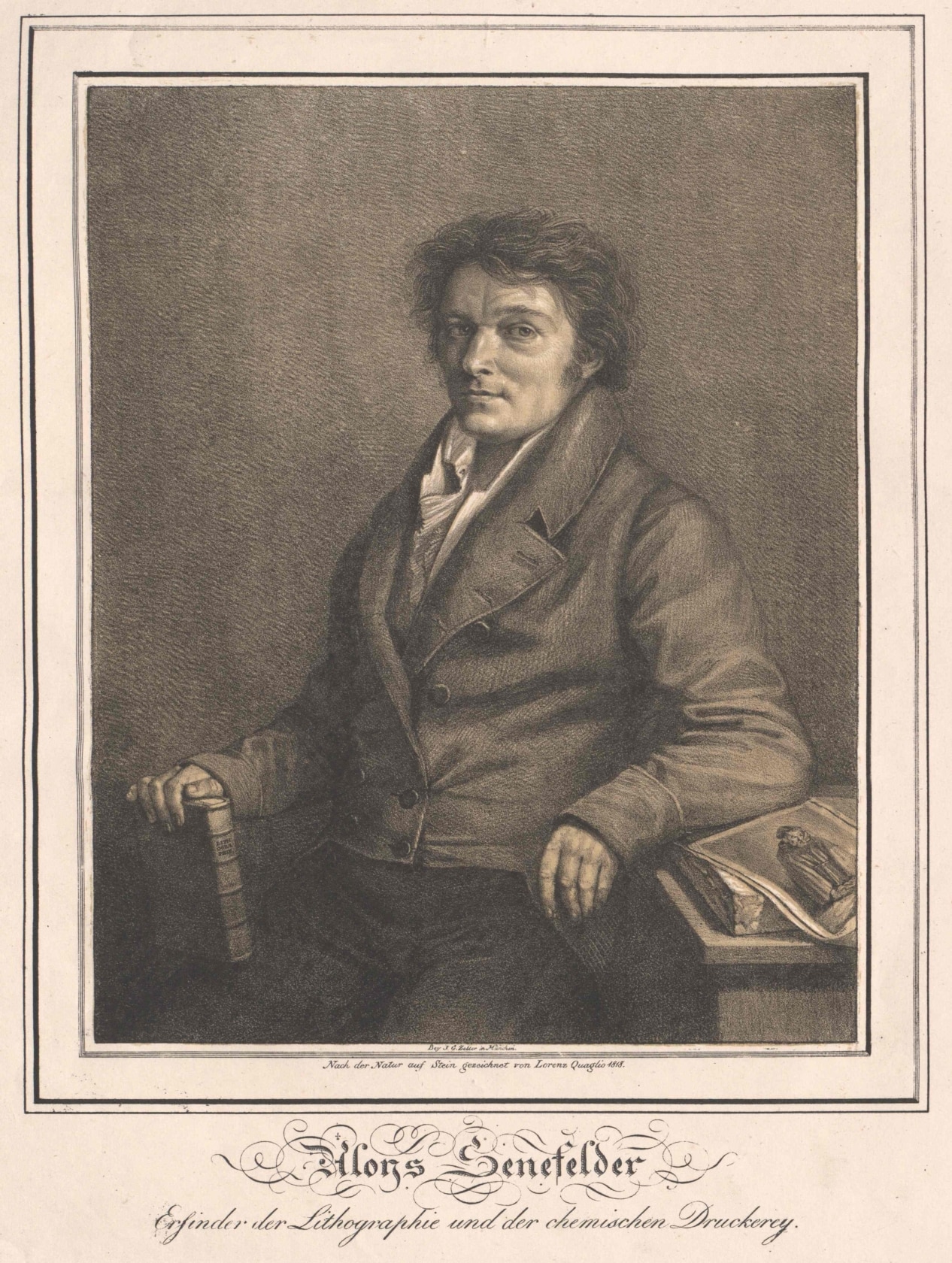

Invented in 1789 by German playwright Alois Senefelder to reproduce scripts and sheet music, lithography was the first new printmaking technique introduced since the invention of etching and engraving in the Renaissance. Predicated on the polarity of oil and water, the lithographic process involves the rendering of an image with an oil-based material, often a greasy crayon, onto a flat stone surface, which is then wetted, inked, and printed. Due to the hydrophobic nature of the drawing material, the ink affixes only to the portions of the stone touched by the artist’s greasy crayon while the remaining portions of the porous stone retain water, repel the oily ink, and remain blank.

Table of Contents

History of Lithography

Unlike engraving or woodcut printing, lithography is a planographic process which means that the ink transfer occurs on a single plane without the sunken grooves of intaglio printing or raised planes of relief printing. Rather, the lithographic stone, ink, and paper are all level with one another.

At the time of its conception, lithography proved to be a cheaper, faster, and more scalable alternative to its antecedent and rival copper plate engraving, which caused lithography to gain popularity in both commercial and artistic spheres. Additionally, lithography held particular appeal to artists who liked the degree of expressivity and line variation achievable through the medium.

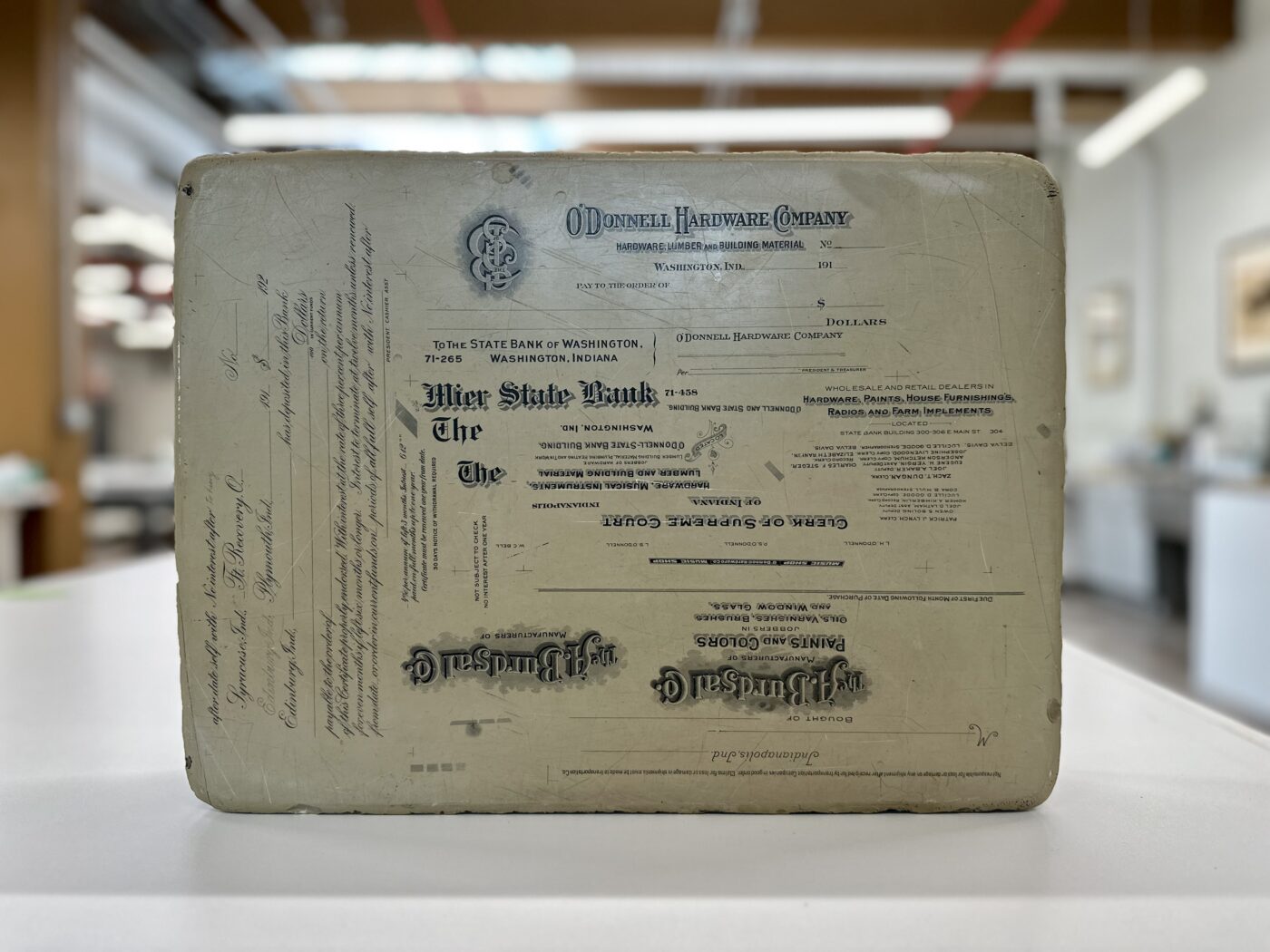

In the years following its invention, Germany rose as the center of lithography with the best limestone quarries located in the Solenhofen region of Bavaria. However, by the early 19th century, France outpaced Germany as the locus of innovation and production in the industry. By the late 1800s, lithography was widely used by some of history’s most lauded artists including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Bonnard, and Edvard Munch to name a few. Likewise, in the commercial sector, lithography became one of the most widely used reproductive techniques to generate necessary and commonplace items such as product labels and packaging, maps, newspapers, documents, and, quite memorably, the large color advertisements that flooded the streets of major metropolises at the turn of the century.

Portrait of Alois Senefelder

Portrait by Lorenzo Quaglio the Younger, 1818, lithograph. Bildarchiv Austria.

Drawing on the Stone

Traditional lithography involves the rendering of the image directly onto a flat limestone slab using an oil-based crayon, pen, or wash, thus permitting a wide variety of mark-making. Treated zinc or aluminum plates are sometimes used instead of a limestone slab, but stone is often preferred because it allows for a richer range of tonal values. Historically, artists have gravitated towards this printing technique because it does not require the technical skill of an engraver or woodblock carver, rather the artist is merely required to draw, a skill familiar to most.

As an autographic process, lithography has the ability to retain the tenor of the artist’s hand without the overwhelming voice of either the medium or the printmaker. Often artists would take advantage of the spontaneity and immediacy permitted by lithography and draw directly onto the stone which was then treated, inked, and printed by a separate entity – the printmaker.

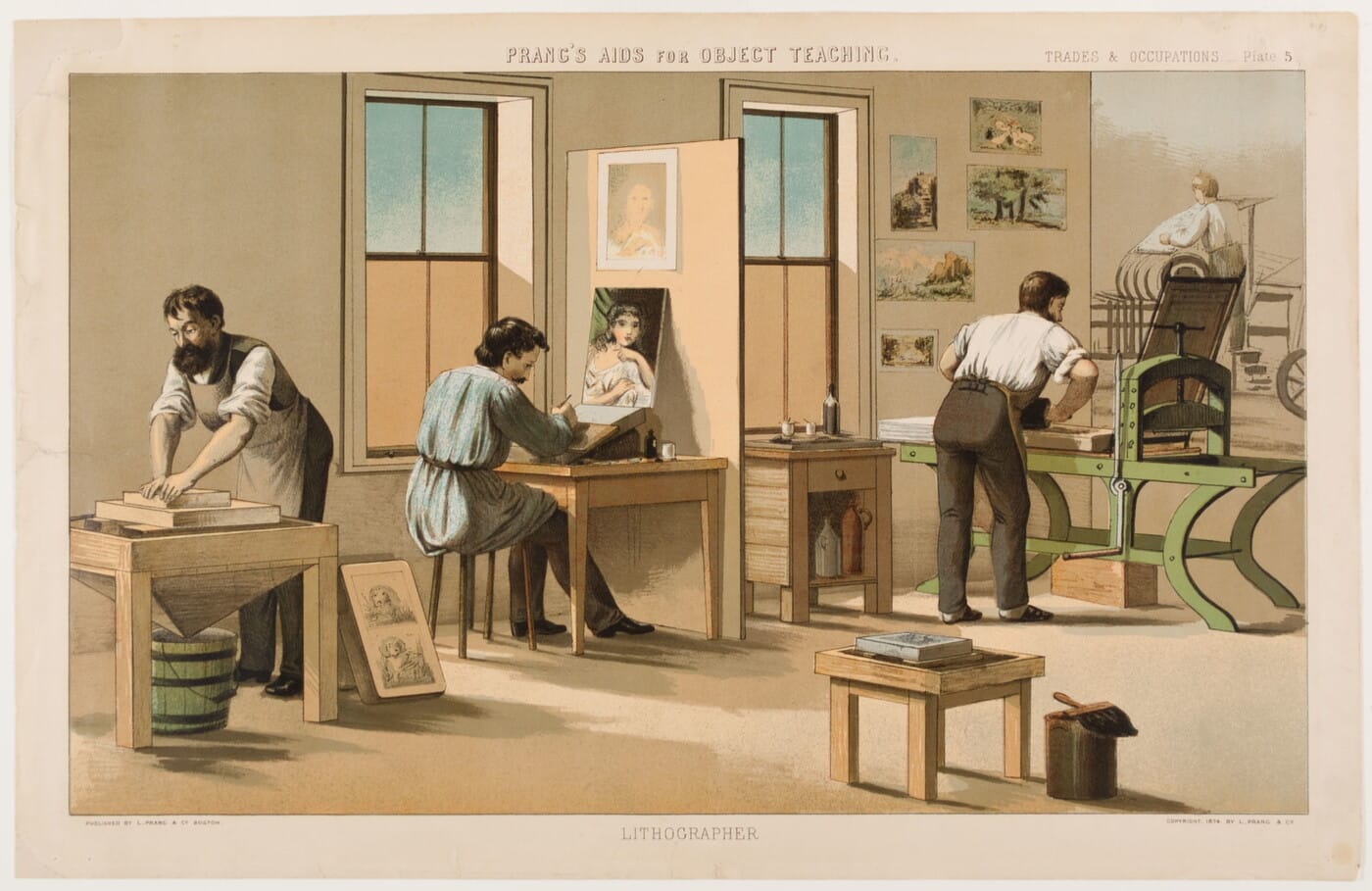

The interior of a printing studio shows the master lithographer and his apprentices at work.

Prang’s Aids for Object Teaching, Lithographer by Louis Prang. Chromolithograph, 1874. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas.

Alternatively, the image can be applied to the stone’s surface through transfer paper. In this process, the artist draws with a greasy material on paper that is then placed face down on the stone and wetted to execute the transfer of the drawing to the stone’s surface. The image can then be reworked as necessary. Image transfers are a valuable process for printing orientation-specific images and symbols such as text, which would otherwise need to be written backward on the stone in order to be printed coherently and in the proper orientation. However, drawing directly on the stone allows for greater definition in the final image and prevents the inevitable presence of paper grain that is retained along with the image in the image transfer process.

Preparing the Stone

Once the drawing is complete, the surface of the stone is treated with powdered rosin and talc, before the application of gum arabic and a mild nitric acid solution. The combination of these substances causes the drawing to be chemically affixed to the stone’s surface and to prevent further grease, such as a stray fingerprint, from settling on the stone. These substances also ensure that the ink, once applied, will be retained only where the artist’s greasy crayon has touched while the blank areas of the stone will repel the ink.

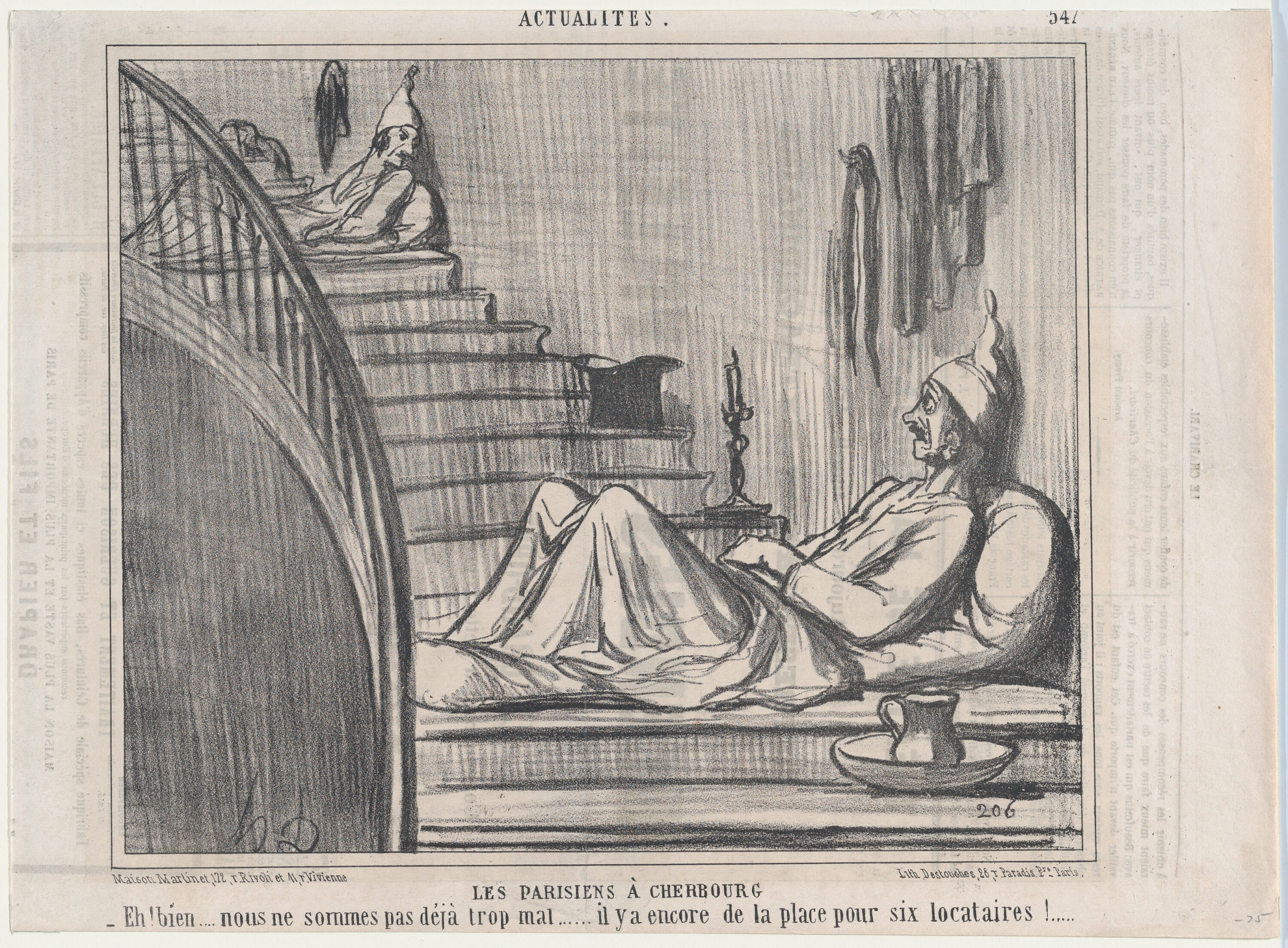

In the 19th century, lithography was used widely to print newspaper and book illustrations

Honoré Daumier, Les Parisiens à Cherbourg, from Actualités, published in Le Charivari, August 16-17, 1858. Lithograph on newsprint. The MET.

Inking the Stone

Next, the stone is wiped down with a lithotine solvent that erases the drawing, leaving behind only a faint trace of it. The stone is then buffed with asphaltum and wiped down with water before the ink is evenly applied using a roller. Due to the hydrophobic nature of the ink, it adheres only to the portions of the stone that were touched by the artist’s greasy crayon. Meanwhile, the ink is repelled from the hydrophilic surface of the stone left untouched by the greasy crayon.

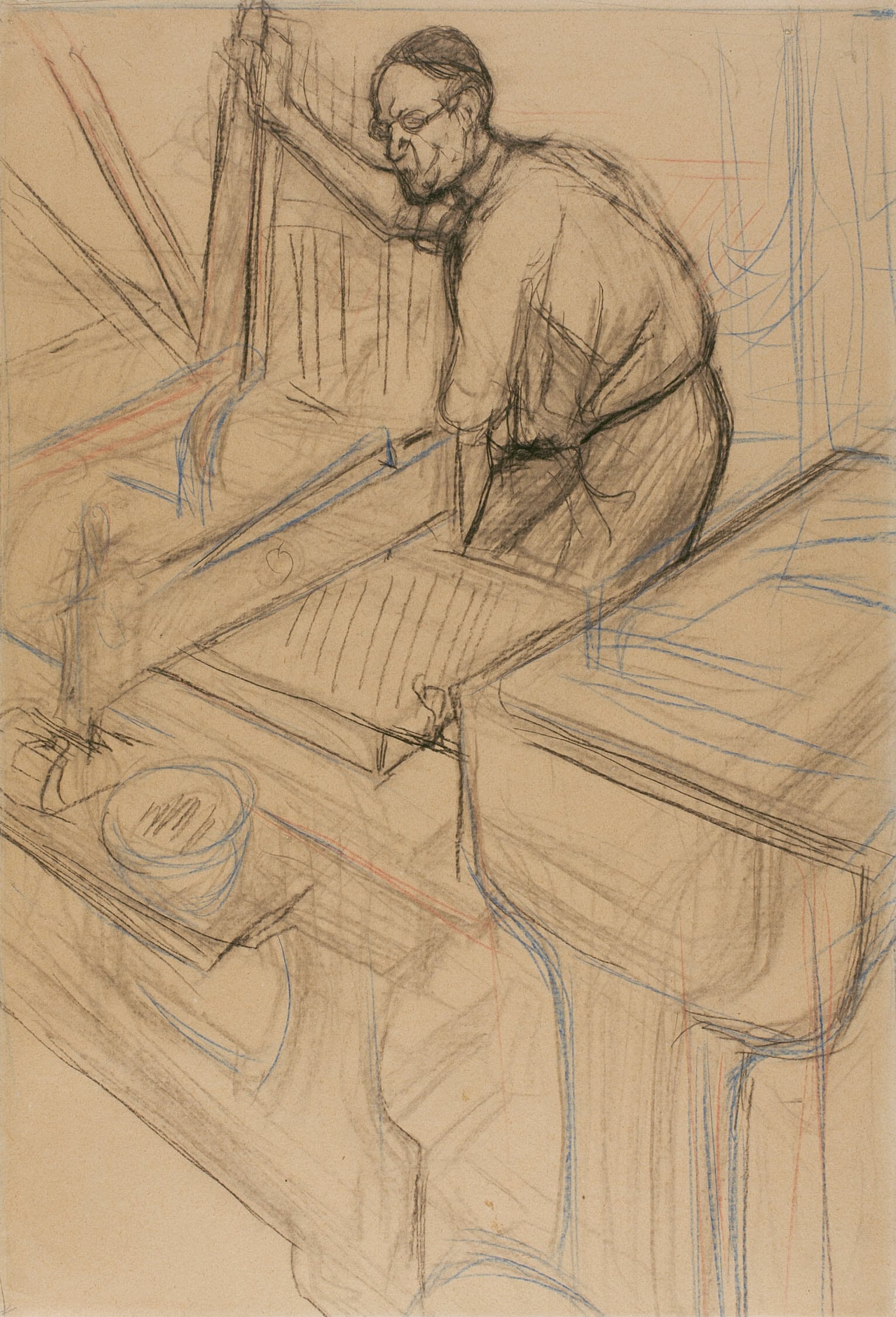

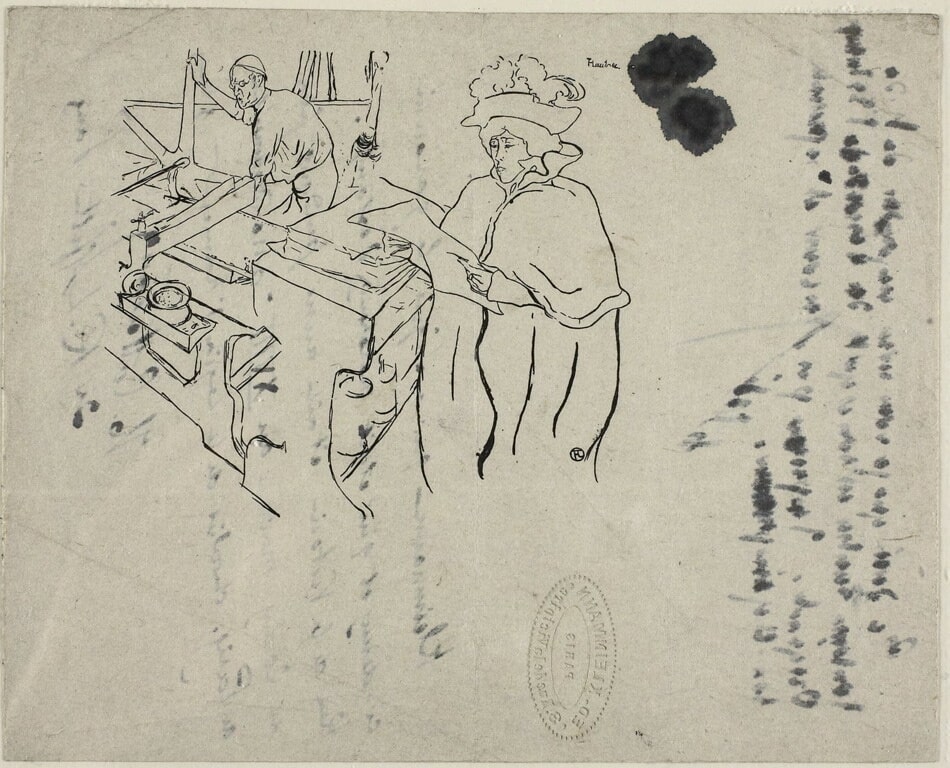

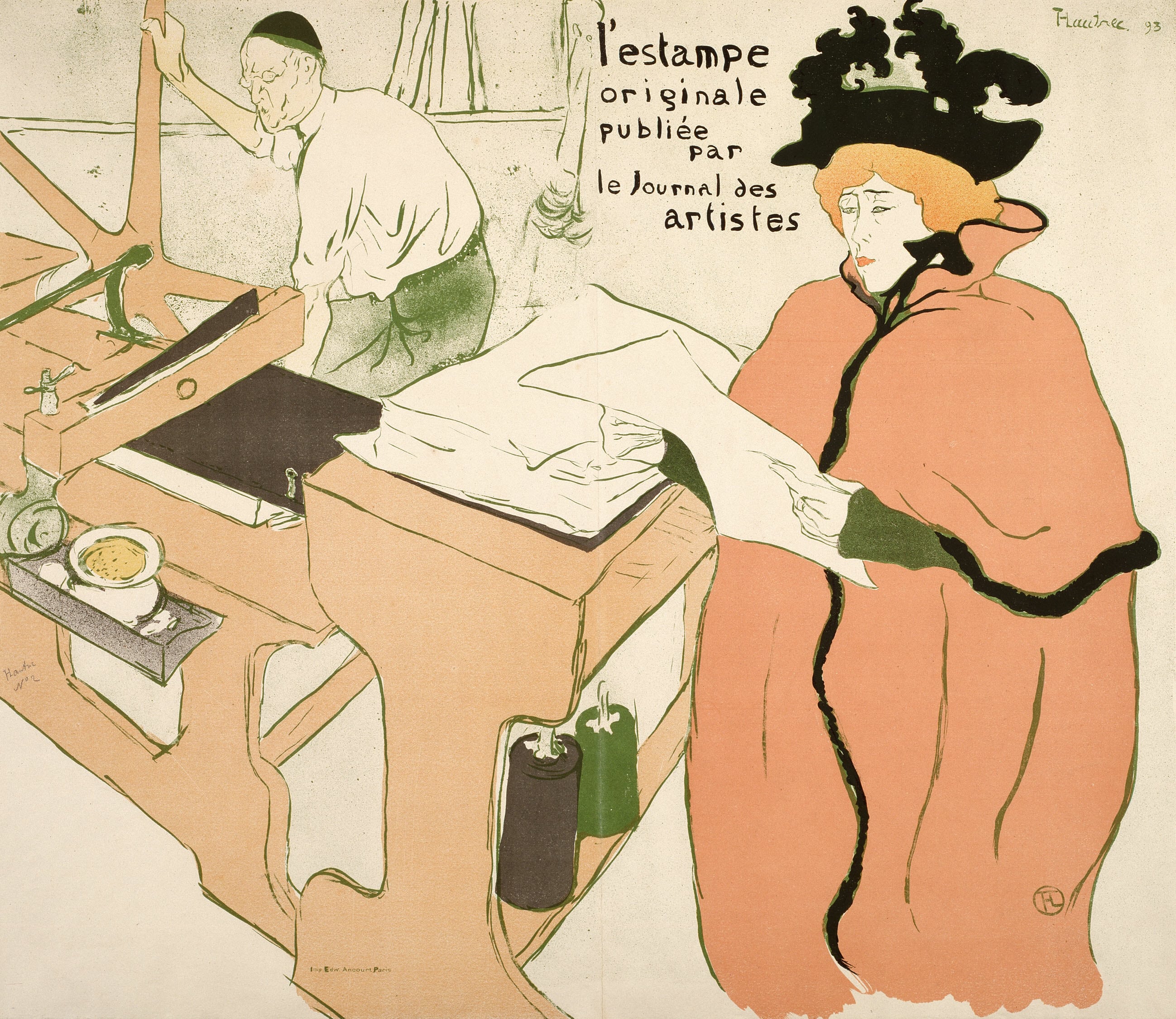

In this sketch, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec depicts his favorite printmaker, Père Cotelle, at work.

Study, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, c. 1893, charcoal, with colored crayons, on tan wove paper. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Printing the Image

Once the stone has been inked, a sheet of paper is laid on its surface, and pressure is applied to consummate the image transfer. The result is a reverse image of the original drawing on the stone. For multicolor prints, the inking and printing processes are repeated as many times as there are colors in a print, for each color requires a separate stone bearing the lines and silhouettes of that color exclusively. Precise registration systems allow printmakers to ensure that the various colors and components delineated on separate stones align properly in the final print.

Lithograph printed in black ink

Cover of L’Estampe originale, with notes, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1893. Lithograph in black on grayish-ivory wove China paper. Art Institute of Chicago.

Lithograph printed in color

Cover for the first album of L’Estampe originale, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1893. Color lithograph on ivory wove paper. Art Institute of Chicago.

Color Lithography

The earliest instances of color lithography appear through the use of a tint stone or secondary stone used to supply a colored background to a black-and-white image. It was not until the late 19th century that advances in color printing technologies caused chromolithography to be used on a large scale. Produced between 1858 and 1860, the Bien edition of John James Audubon’s Birds of America was one of the earliest and finest examples of large-scale color printing. Likewise, the multicolored posters and advertisements of artists like Jules Chéret popularized the use of chromolithography in art and commerce.

Lithographs often appear grainy under a microscope

Audubon Bien Ed. Pl. 231 Blue Jay. Chromolithograph with hand-coloring, 1858-1860.

Identifying a Lithograph

With the ink, stone, and paper existing on the same plane, lithographs do not have plate marks like intaglio prints, but it is sometimes possible to see an area of the paper that has been flattened by the stone. Similarly, the ink of a lithograph lays directly on the paper surface without depressions like those detectable in relief prints. Under magnification, a lithograph often appears grainy with varied linework but does not have the uniform dot pattern found in certain offset and digital prints.

Endorsed by an attractive female, Chéret’s chromolithograph advertises Saxoléine paraffin oil as a stable and reliable fuel for your domestic lighting needs.

Saxoleine, Jules Chéret color lithograph on cream wove paper, 1893. Art Institute of Chicago.

The Efficacy and Practicality of Lithography

As a fast, inexpensive, and scalable process, lithography revolutionized printmaking and allowed for a broader range of mark-making previously unachievable through extant printing methods. Antony Griffiths, author and former Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, points out:

“Lithographic stones or plates in general yield a fairly large number of impressions without deterioration, but much depends on the quality of the surface, the method of drawing, the delicacy of the work and the skill of the printer.” (Griffiths 1996, 104)

In addition to yielding a sizeable number of impressions before needing to be redrawn, a lithography stone can be reused indefinitely by grinding down the surface to erase the previous image and prepare it for the next. The reusability of the stone, in turn, eliminates the continual material costs associated with engraving or relief carving to acquire new metal sheets or wood blocks for each print. Lastly, as a process that does not require the technical acumen of an engraver or woodblock carver, lithography is an accessible medium. In conclusion, lithography is an incredibly democratic and efficient reproduction technique for its low costs, high yields, and breadth of imagery that can be produced.

References:

Ives, Colta. 2000 – present. “Lithography in the Nineteenth Century.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lith/hd_lith.htm (October 2004)

Griffiths, Antony. 1996. Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lambert, Susan. 2001. Prints: Art and Techniques. London: V & A Publications.