Information

Evolving Impressions – Unfolding the History of Prints as Art Objects and Collectibles

From their conception, prints have served both constructive and aesthetic purposes.

Table of Contents

In contrast to more orthodox mediums such as painting and sculpture, from its conception, printmaking melded the pragmatism of commerce with the aesthetic concerns of fine art. As multiples that are mechanically produced at a low cost in comparatively large numbers, prints are a democratic medium that unites high and low art, beauty and functionality, and art and commerce. As a result, print media occupies a unique place in the history of art and art collecting. This article will trace the development of prints as fine art objects and the corresponding collecting practices.

The Collector of Prints, Edgar Degas, 1866.

With a large green portfolio at his feet, the print collector adds yet another botanical engraving to his collection.

Prints in Renaissance Europe

Developing out of the metalworking trade, etching and engraving were initially used to produce practical items such as playing cards, devotional images, and instructive material for children (Parshall 1994, 27). Likewise, woodblock printing, which had existed for centuries in East Asia, gained traction in Europe as a quick and efficient means of producing book illustrations – a need that had arisen with the introduction of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press in the latter half of the 15th century.

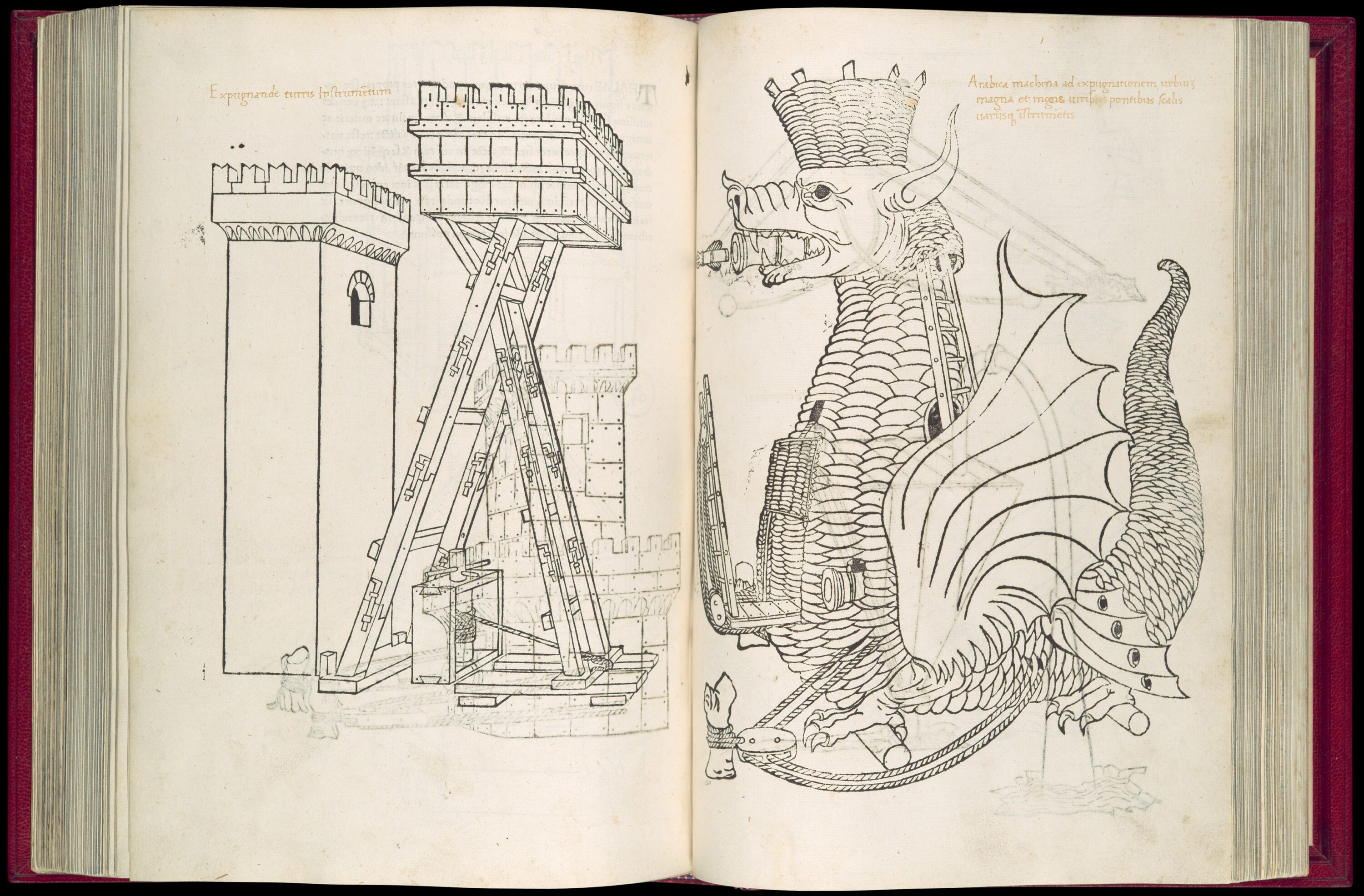

A 15th-century instructive illustration from a book on military equipment and strategies.

Matteo de’ Pasti, On the Military Arts, Woodcut book illustration, 1472. The MET Collection

In addition to its practical use, printmaking was welcomed by artists who embraced the reproductive possibilities of the medium as a sophisticated form of self-advertisement, disseminating their imagery in a portable and inexpensive manner (Parshall 1994, 9). Likewise, prints were assembled by artists and workshops who used the material to train young apprentices in the ways of the masters. However, it was not until the late 1480s that prints were gradually recognized as art objects (Parshall 1998, 22).

Artists such as Albrecht Dürer were instrumental in influencing the acceptance of prints as fine art.

Adam and Eve. Engraving, 1504. The Art Institute of Chicago

During this time, many artists enlisted the technical acumen of a workshop to reproduce their art while others elected to explore the possibilities of the print medium themselves by carving their own metal plates and wood blocks. Often it was the combined effort of the artist and the workshop that brought the print to fruition. Once recognized as fine art, prints proved instrumental in changing the patronage paradigm that had pervaded the arts by making art collecting increasingly democratic.

The Rise of the Print Publishing House & Systematic Collecting in Early Modern Europe

With the rise in demand for books and book illustrations, the early 16th century heralded the introduction of major print publishing houses – such as those in Antwerp and Haarlem – that combined the two industries into one. These print publishers issued vast numbers of prints depicting all manner of subjects including reproductions of notable works of art, historical, secular, or religious scenes, ornamental patterns, architectural models, and portraits. The imagery itself was often sourced from artists who were hired to produce a drawing or painting that was then etched, printed, and published under the direction and accreditation of the publishing house. Only on select occasions when the artist’s name was sure to improve sales was his or her name included in the printed work. The printing plate was typically retained by the print publishing house and reused at their discretion.

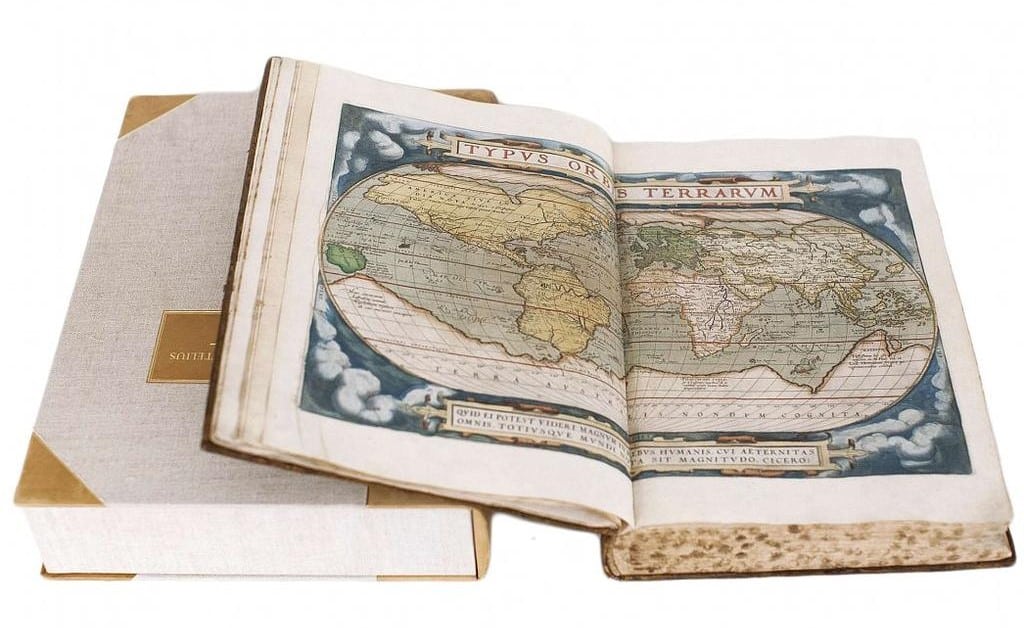

Crucial to the success of Ortelius’ magnificent atlas was his connection with the Antwerp printing house of Christoph Plantin.

Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, or The Theater of The World Atlas, 1579.

view productIntended for a literate class of patrons, most prints were issued uncolored in organized sets that could be collected in part or as full sets. If the collector was particularly wealthy, they might elect to have the prints colored by an illuminator’s workshop. For the first time, the possibility of owning a representation of every biblical scene, historical event, or cataloged botanical specimen was realized. The limitless potential for collecting within any given category accompanied by a glimmering promise of completion spurred on many collectors who filled their libraries and curiosity cabinets with more and more prints.

In addition to lining the shelves of enthusiastic collectors, printed folios were used by professionals as reference material in their respective disciplines. For example, folios of ornamental designs and organic motifs were used by those in the textile, ceramic, and architectural trades by providing designs to adorn their work.

Printed designs such as these rings could be used by jewelers and goldsmiths to craft their wares.

Pierre Woeiriot de Bouzey II, Four Rings, Plate 31 from ‘Livre d’ Aneaux d’ Orfevrerie’. Engraving, 1561. The MET Collection

The primary collectors of prints fell into three categories: the lover of history who collects portraits, maps, and depictions of historic events; the lover of art who collects representations of each artist or school of painters’ work; and the collector who amasses prints issued by a particular engraver without regard for the subject matter or original artist (Griffiths 1994, 47). Despite their popularity among collectors, prints “did not become a regular feature of interior decoration until well into the seventeenth century” (Parshall 1998, 20). Rather they were stored in drawers and portfolios for occasional examination often performed in private or at the explicit invitation of the owner. The occasion of looking at a print, therefore, was a predetermined and deliberate event (Bindman & Carvalho, 20).

Lithography as the Language of Revolution, 19th-century France

Riding high off the wave of the Industrial Revolution, the 19th century heralded advances in printing technology and the use of color lithography in place of engraving to produce popular media, book illustrations, official documents, and commercial product labels. By the end of the century, chromolithography proved to be a revolutionary medium embraced by avant-garde artists who sought to dismantle the traditional hierarchy of the arts by embracing the quotidian and commercial medium of lithography as a primary mode of expression.

Printmaking was the language of modernism and rebellion in the late 19th century.

Color lithograph of Jane Avril by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1893.

Chéret melded commercial and artistic aesthetics through the colorful new medium of chromolithography.

Loïe Fuller by Jules Chéret. Color lithographic poster, 1893.

Observations from the late 19th century describe Paris as “a brilliantly colored proletarian museum” with poster advertisements such as those by Jules Cheret papering the streets and blending commercial and artistic aesthetics through the colorful new medium of chromolithography (Bindman & Carvalho, 30). Simultaneously, collective print exhibitions, albums, and artistic journals actively promoted print media as the language of modernity, which greatly increased public awareness and collecting of original prints (Bindman & Carvalho, 26).

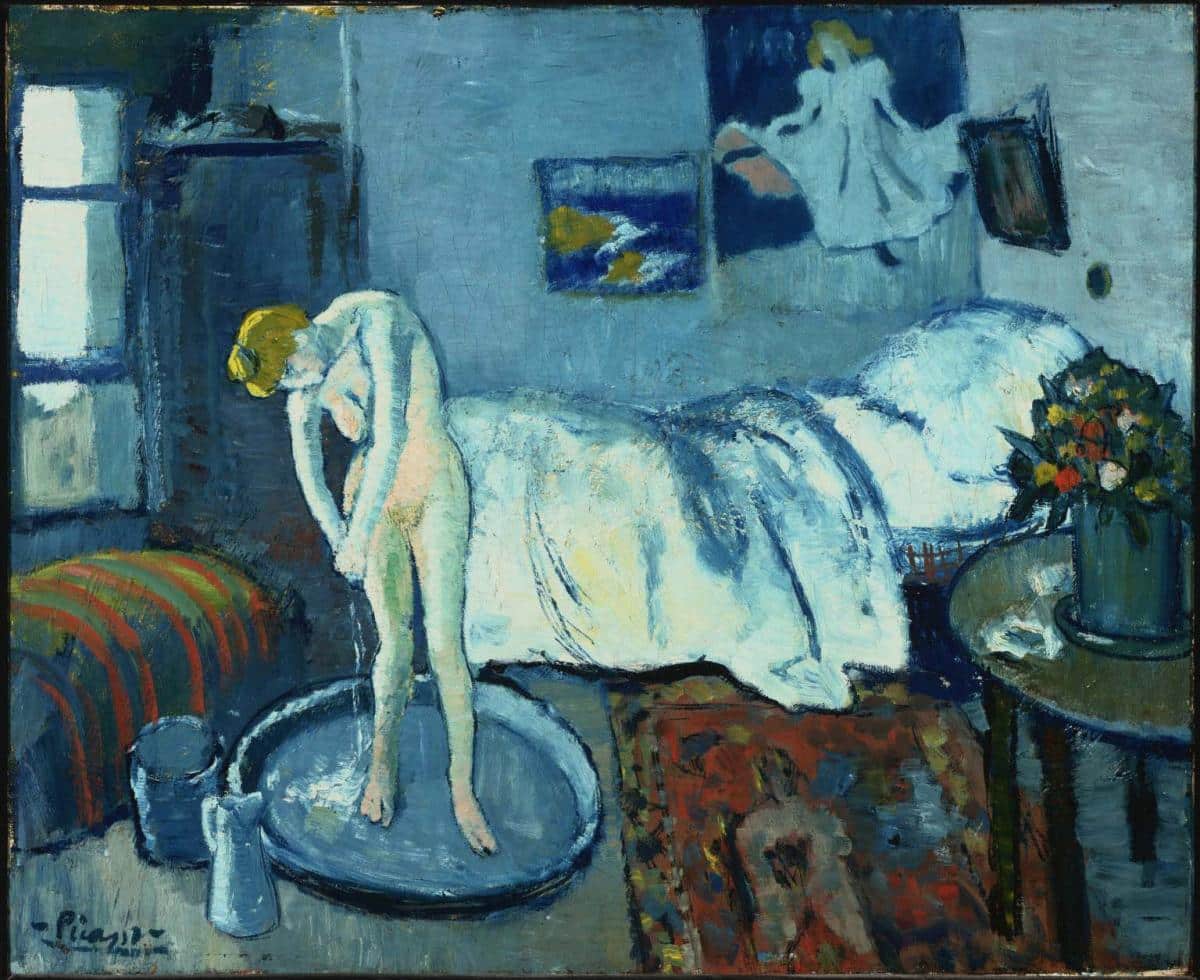

Pablo Picasso, The Blue Room, 1901.

The Phillip Collection.

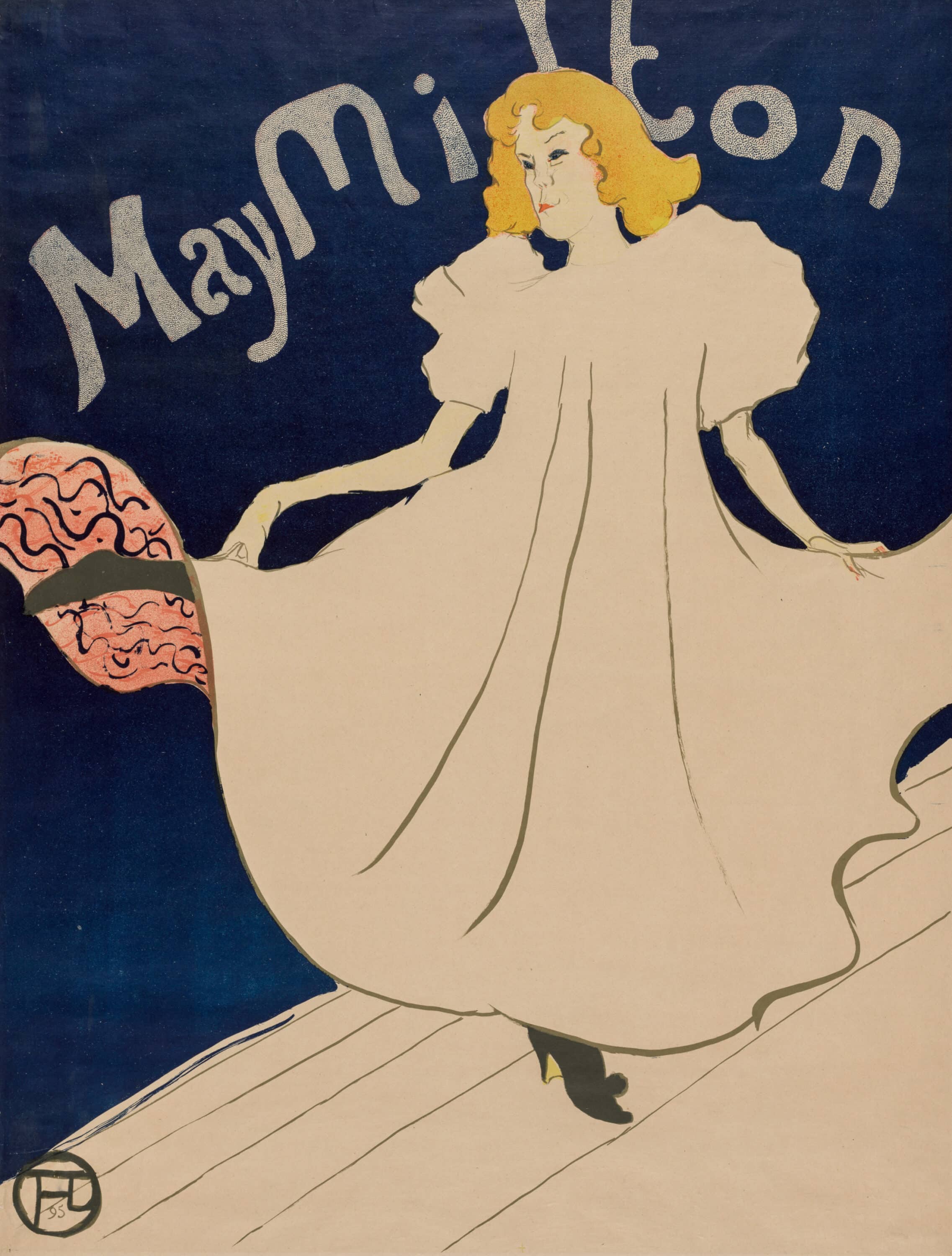

Even Pablo Picasso’s The Blue Room (1901), which is probably set in his Montmartre studio, shows Toulouse Lautrec’s May Milton poster hanging on the wall.

May Milton by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Color lithograph, 1895. The Art Institute of Chicago.

At the same time, an increase in print dealers rose to meet the demands of bourgeoise collectors who sought to furnish their interiors with prints. In fact, some enthusiastic collectors were known to peel lithographic advertisements off the walls lining the streets of Paris before they had a chance to dry (Bindman & Carvalho 2017, 5). Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho, curator of prints and drawings at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, explains that “The idea of appropriation from the streets was very much a bohemian idea, and part of the anarchist movement too. They liked the heroics of the fact that they were a bit ripped or discolored—it gave them even more cachet” (Bindman & Carvalho 2017, 6).

Thus by the end of the century, prints were perceived not only as individual works of art and vehicles for creative expression but also as part of a distinctively modern language of art, revolution, and progress.

References

de Carvalho, F. R. R., & Bindman, C. (2017). “Small Apartments and Big Dreams: Print Collecting in the Fin de Siècle.” Art in Print, 7(1), 3–6. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26408780

Griffiths, Anthony. (1994). “Print Collecting in Rome, Paris, and London in the Early Eighteenth Century.” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin, 2(3), 37–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4301495

Parshall, Peter. (Winter 1998). “Prints as objects of consumption in early modern Europe.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies; Durham Vol. 28, Iss. 1: 19-36.

Parshall, Peter. (1994). “Art and the Theater of Knowledge: The Origins of Print Collecting in Northern Europe.” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 2:7–36.

Thompson, Wendy. (October 2003). “The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prnt/hd_prnt.htm

Hortus Eystettensis - Deluxe Edition - Antique Originals

Besler Deluxe Ed. Pl. 311, Florist’s carnation, White-flowered thyme, Lavender cotton

Original Engraving | circa 1613 | 22 x 16.5 inches

Family of Hummingbirds - Antique Originals

Original hand-colored lithograph | circa 1849 – 1861 | 21 ¾ x 15 inches

Havell Edition – Antique Originals

Original Havell double-elephant folio hand-colored Engraving | circa 1827-1838 | 38.25 x 25 inches

Les liliacées - Antique Originals

Antique original color stipple engraving; circa 1802 – 1816