Information

Exploring Audubon’s Woodcock – The Havell Edition

An analysis of Audubon’s technical and creative approach to rendering the American Woodcock

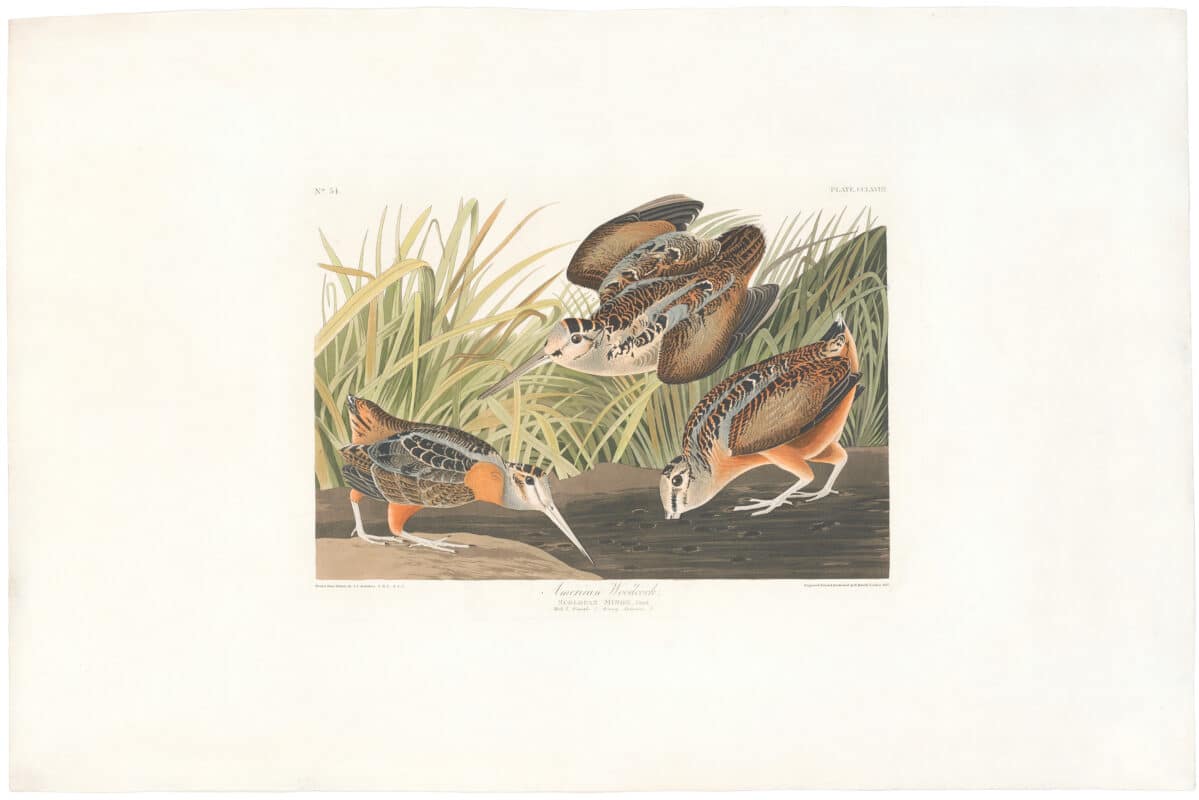

One of the remarkable aspects of John James Audubon’s print of the American Woodcock is that he has placed the viewer on ground level with the subjects, as though he or she is a hunter, bird-watcher, or perhaps an artist concealed behind the long grasses of the eastern wetlands of America.

Table of Contents

From this privileged position, we can observe the habits of the small birds as they forage for food. The naturalistic cadence of the birds’ movement is captured by Audubon who devised a meticulous system for representing nature. Valuing precision, Audubon methodically employed a compass to trace the outline of his specimens in order to replicate their exact measurements in his rendering. Similarly, Audubon insisted on drawing directly from nature and crafted an innovative technique for mounting and positioning his specimens. Composed of a gridded board and wire, his device allowed him to adhere his specimens in naturalistic positions on a vertically slanted board, where, in classical still-life format, he would place his paper flat before the subject and begin his rendering. This approach, coupled with his extensive observation of birds in the wild, allowed Audubon to reanimate his specimens, and to transfer their vivacity onto the page through watercolor and graphite.

Audubon Havell Ed. Pl 268, American Woodcock

Original Havell double-elephant folio hand-colored Engraving; circa 1827-1838

Anthropomorphizing the Bird

When viewing the American Woodcock, we are immediately engaged with the dynamism of the trio depicted. In a manner suggestive of a nuclear family, Audubon captures a male, female, and young fledgling of the species rendered in their native marshy habitat. Centrally oriented is the female woodcock, who swoops down to offer the observer an optimal view of her downy dorsal contour. Accented with pale bluish-gray, tints of light umber, and flecks of rich black and soft brown tones, the female woodcock displays a subdued earthy coloration that aids her discretion among the brush where she lives. Likewise, the male and young woodcock feature similar coloring, but in significantly richer tones and with a greater degree of umber and burnt orange lining the torso and throat. Below her to the left and right the male and fledgling woodcock complete the triadic composition of the print.

Audubon identifies each member of the group through a numerical ledger at the central base of the print below the title and scientific identification of the species; American Woodcock / Scolopax Minor, Gmel. / Male 1. Female 2. Young Autumn 3. To the left stands the young woodcock keenly observing its male elder, who, with seasoned precision, plunges its beak into the marshy earth in search of sustenance. The numerous perforations in the muddy ground suggest a fruitful harvest of worms, which serve as the primary source of nourishment for woodcocks. By visualizing the variations of gender and maturity through the inclusion of the three birds, Audubon creates a codification of the American woodcock while also humanizing the subjects through the inclusion of an underlying familial structure.

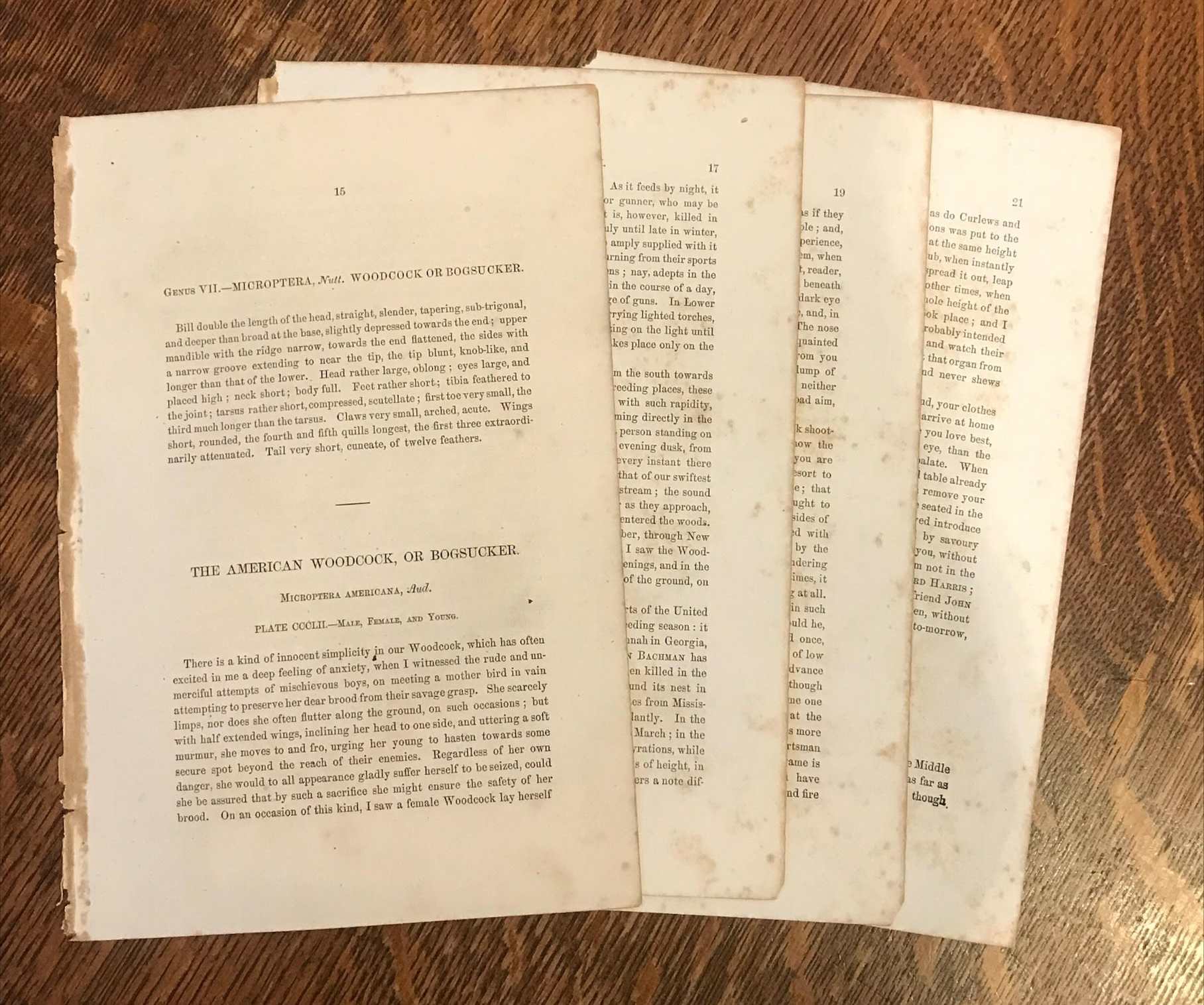

Excerpt on the American Woodcock from Audubon’s Ornithological Biography.

In 1831, Audubon published the Ornithological Biography as a written correlative to the Birds of America.

Hunting the Woodcock

The woodcock, however, serves as more than an aesthetic and scientific specimen; it was also a popular game-bird. While trekking through the vast wilderness of the American backwoods, Audubon frequently hunted the woodcock for sustenance. In his book Ornithological Biography, Audubon details the utter satisfaction of returning home after a long day of fowling to enjoy the tasty bird:

How comfortable it is when fatigued and covered with mud, your clothes drenched with wet, and your stomach aching for food, you arrive at home with a bag of Woodcocks, and meet the kind smiles of those you love best, and which are a thousand times more delightful to your eye, than the savoury flesh of the most delicate of birds can be to your palate. (Audubon 1831, 21)

Today a similar sentiment is shared by hunters who likewise pursue the woodcock for its scrumptious flavor. By positioning us in close range to the family of woodcocks, Audubon offers up the birds for our visual delectation and collapses the distance between viewer and subject by capturing the woodcock’s intricate details with his brush.

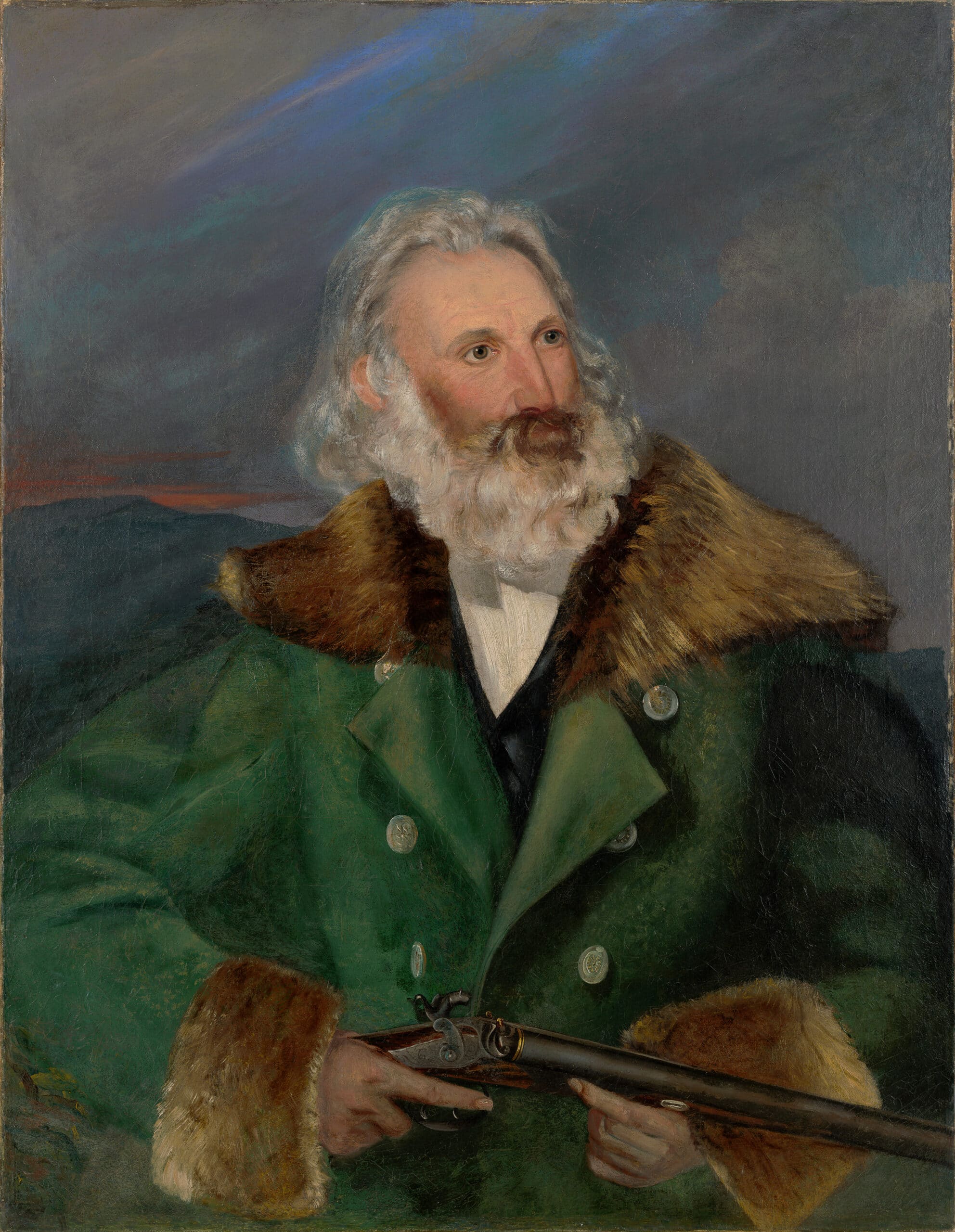

Portrait of Audubon painted by his son John Woodhouse

From the Oppenheimer American Museum of Natural History Edition of Audubon’s Watercolors

view productTechnical and Mechanical Process of Creating the Artwork

While initially rendered in paint, Audubon’s watercolors were but the initiatory step in the creation of what he considered to be the final work of art. Rather, he considered his watercolors to be reference material for his engraver, Robert Havell Jr., who operated a print studio in London and worked with Audubon from 1827 until 1838. Havell and his studio would transform Audubon’s watercolors into luminous engravings with hand-applied watercolor. The final product, an extensive folio of prints titled Birds of America, was then sold on a subscription basis over the course of more than a decade. The American Woodcock is plate number 268, which can be deciphered in Roman numerals on the top right-hand corner of the print. Likewise, the part number, No. 54, is visible in the upper left-hand corner of the print. These numbers refer to the prints’ unique place within the overall corpus, Birds of America.

Audubon’s Watercolors, Pl. 268, American Woodcock, published by Oppenheimer Editions

The process of engraving itself greatly informs the overall effect of the print. Upon closer inspection, the perimeter of the immediate image is delineated by a slight embossment pressed into the page when the copper plate was run through the printing press. This visual effect causes the print to float on the larger, double-elephant folio sheet of paper, which frames and brings into stark relief the central subject matter. Likewise, the delicate and intricate linework throughout the print evokes the elegance and fragility of the birds. Lastly, the hand-coloring process of the print allows each work of art to possess a unique effect despite the uniformity of their production.

To the left is the incised copper plate used to render the print on the right, Audubon’s Havell edition Pl. 308, Tell-tale Godwit, or Snipe.

Photo of copperplate attributed to Friends of Audubon.

Commenting on Audubon’s innovative approach to scientific illustration, Roberta J.M. Olson, Curator of Drawings at the New-York Historical Society and author of Audubon’s Aviary, observes that “The sensations he communicates of being embedded with the birds in their natural habitats lend an excitement to his cinematic descriptions that is lacking in the work of his predecessors” (Olson 2012, 41). The embeddedness that Olson discusses is discernible through the sense of immediacy we get from viewing the American Woodcock. Shrouded in the brush and tall grass of the wetlands, we are made privy to the intimate space inhabited by the assemblage of birds before us. The curvature of the grass billows to echo the silhouettes of the bird’s bodies as they move in harmony with nature. The simultaneous dynamism and unanimity of Audubon’s Woodcock trio creates a visual and metaphorical balance that draws in the viewer for a closer look.