Birds and Animal Art

The Abyssinian Bird Portraits of Louis Agassiz Fuertes

A consideration of the creative techniques and viewer-object relations in Fuertes’s watercolors

Often hailed as the successor to Audubon in the lineage of American ornithology, Louis Agassiz Fuertes swiftly gained recognition for his veristic bird portraits. Though each artist’s work is stylistically very distinct, their respective contributions to the development and advancement of ornithological art are both significant. One collection of Fuertes’s watercolors made on his expedition to Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia) is particularly striking for a number of reasons. Firstly, the paintings capture Fuertes’s advanced technical acumen and sensitivity to color, light, and anatomical form. Secondly, and perhaps more significantly is the manner in which Fuertes presents his bird as self-possessing subjects who recognize and reciprocate our gaze. Consequently, the viewer is made implicit in the bird-portraits in that our presence is recognized by the subject.

It was 1926 when Chicago sportsman and writer James E. Baum approached Fuertes with an invitation to travel to Abyssinia to observe the foreign wildlife there. He writes convincingly to Fuertes: “If a man should come to you and ask: ‘What is the strangest country in the world to-day? Where is the bird life the most curious and plentiful?’ You would unquestionably answer both by one word – Abyssinia. All right. Now that we have established the desirability of going there, what do you say to going with me next September?” (Robert McCracken Peck, A Celebration of Birds: The Life and Art of Louis Agassiz Fuertes, p. 141) After agreeing upon the desirability of the venture, the two men were able to garner the financial support of the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Daily News for the endeavor. Accompanied by a group of fellow naturalists, including Wilfred Osgood, the curator of zoology at the Field Museum, the expedition set out to observe and record the birds of Abyssinia.

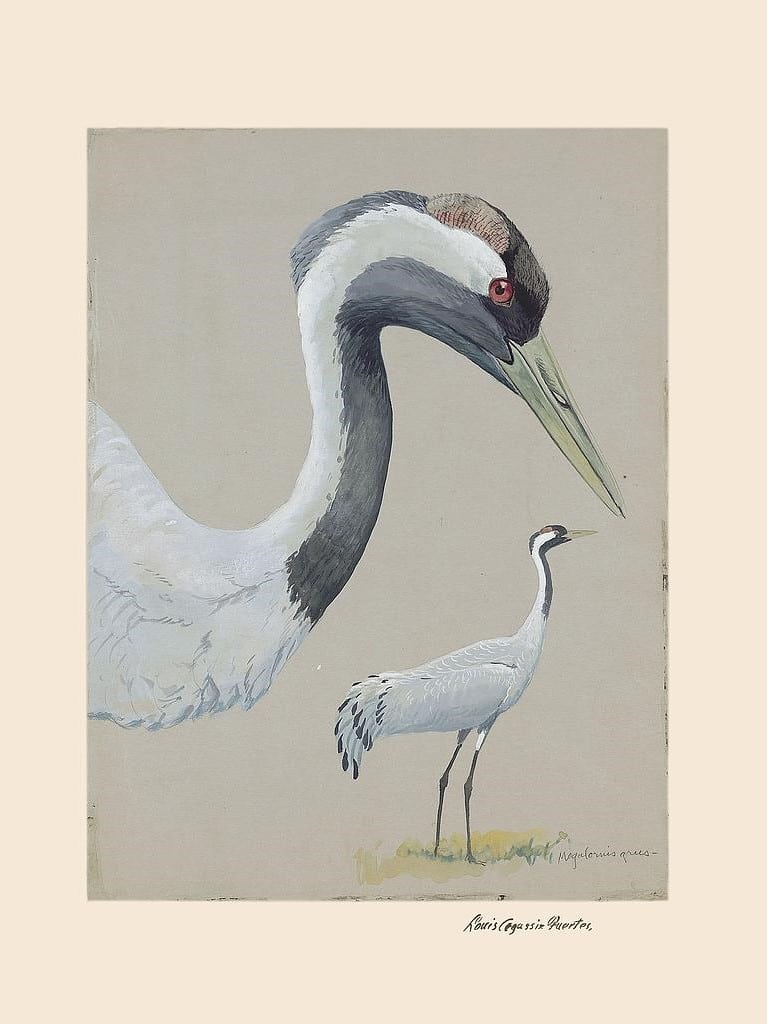

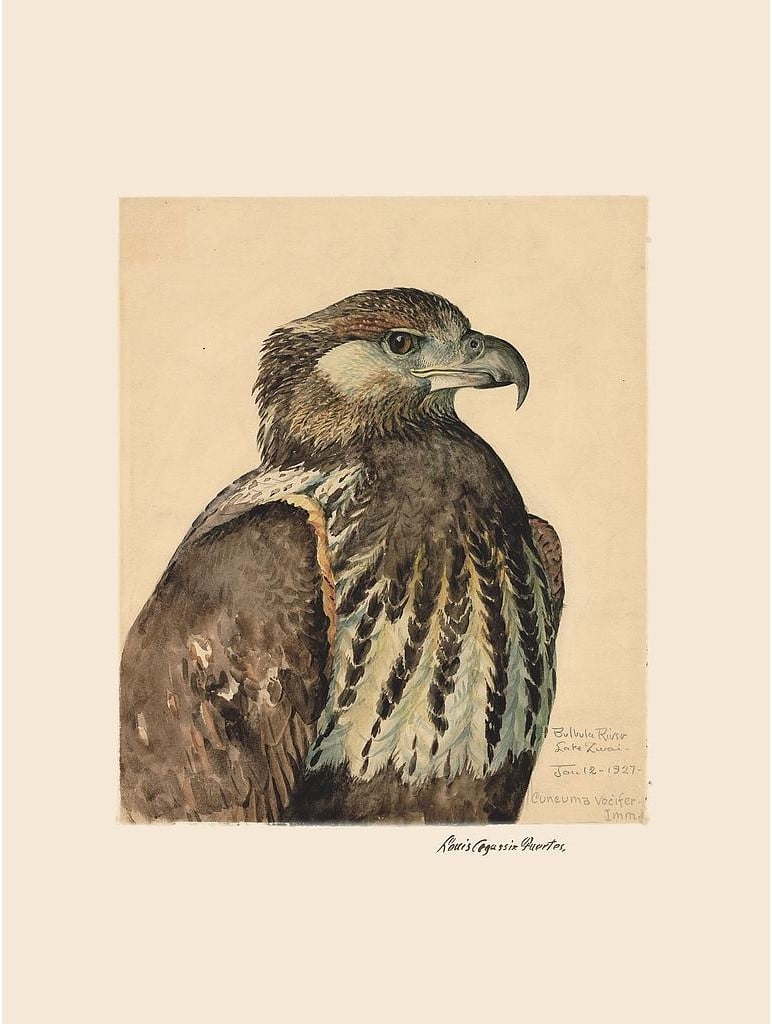

The expedition proved fruitful with Fuertes producing a great number of bird portraits. Take for example Fuertes’s Pl. 26, African Lammergeyer in which the positioning of the bird in profile summons visual reference to classical portraiture traditions such as those found in Pierro della Francesca’s The Duke of Urbino. Here the Lammergeyer appears regal and composed, but possessing the potential to be incredibly fierce if provoked. While on the expedition in Abyssinia, Fuertes tended to focus his field sketches and watercolors on aspects of the birds that would not be preserved once the specimen was killed and taxidermied. Accordingly, many of his watercolors capture highly detailed renderings of the bird heads because it is the eyes, facial tissue, and expression that will be lost once the bird is killed. Additionally, most of the Abyssinian paintings were done as life-size specimen studies.

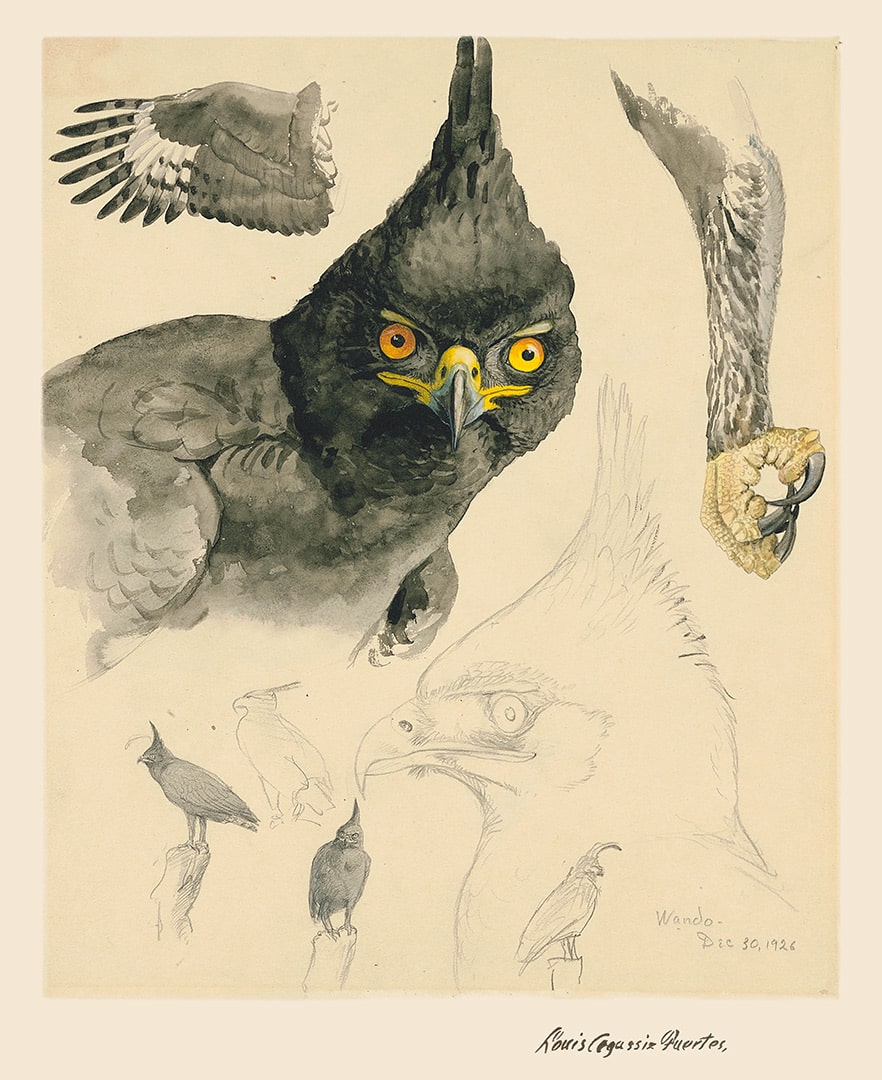

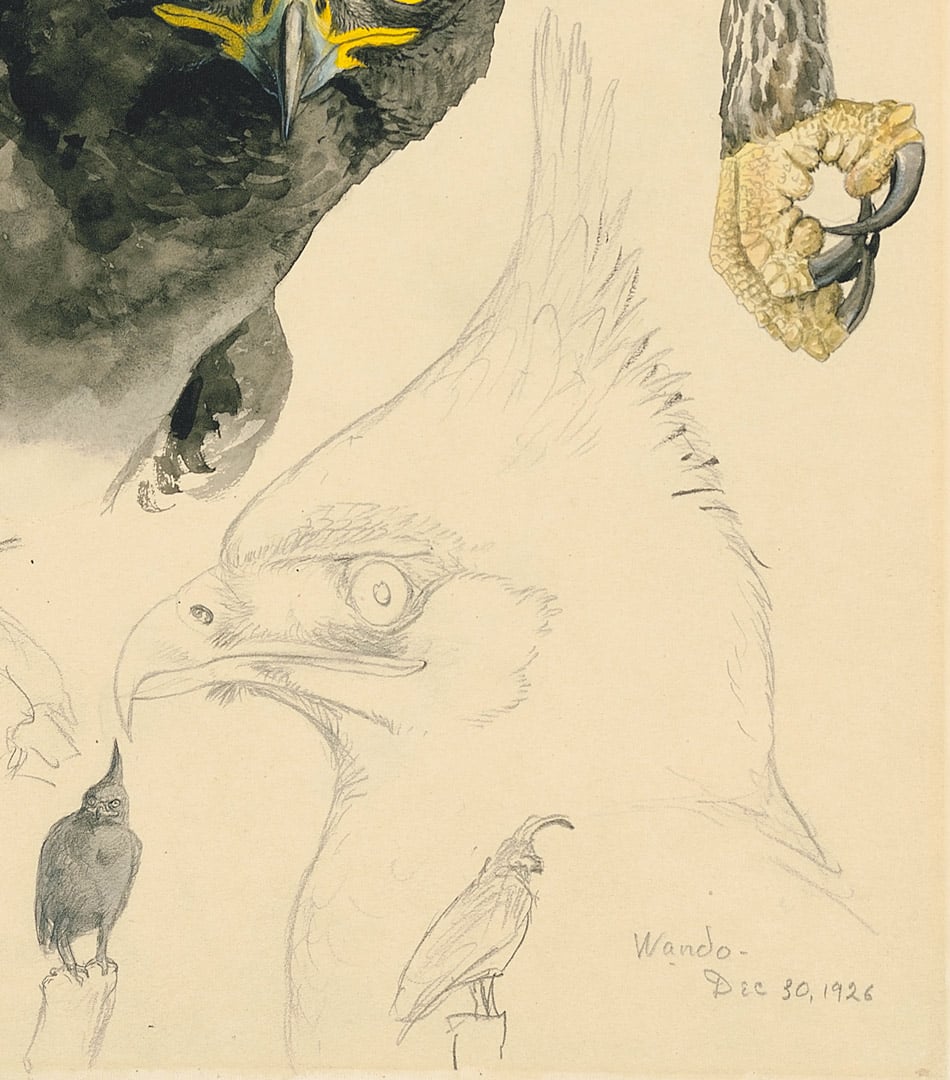

Similarly, there is a startling ferocity to Fuertes’s watercolor portrait of the Long-crested Eagle, Pl. 21. This highly-refined field sketch captures the bird from all angles in diagrammatic fashion. Smaller sketches towards the bottom margin give us an idea of the posture of the bird while at rest. Meanwhile, a light graphite sketch indicates the bird’s profile, and three fully developed watercolor sketches of the talon, an outspread wing, and bust complete the portrait. The primary point of engagement with this piece is the unwavering gaze of the eagle, who, eyeing us up, defies any notions of static complacency. Rather, the bird-subject is vigilantly watching us, and, as a result, we feel prompted to reciprocate the eagle’s gaze.

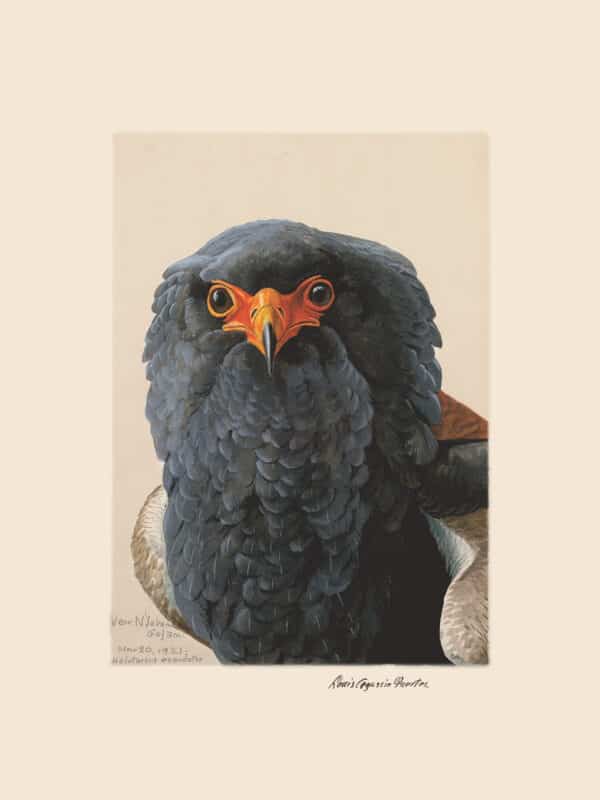

Likewise in Pl. 19, Bateleur the bird maintains an equally commanding presence. The fontal orientation of the Bateleur, coupled with its steady gaze, encourage us to recognize the autonomy and self-possessing character of the bird. Rather than pose to be looked at, the bird is positioned to make us slightly uncomfortable and on edge when viewing this watercolor. This prompts us to actively engage with the painting rather than passively encounter it.

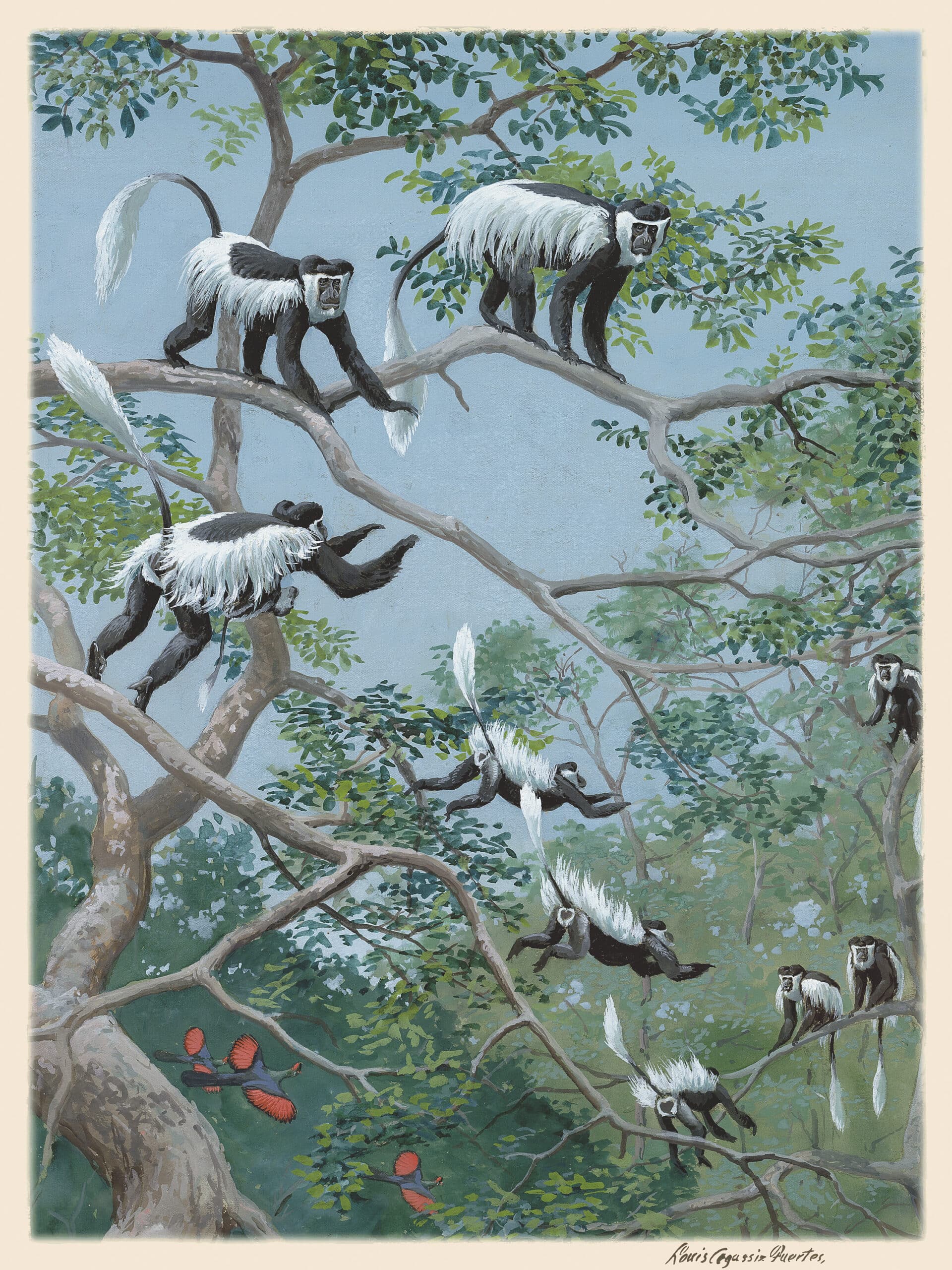

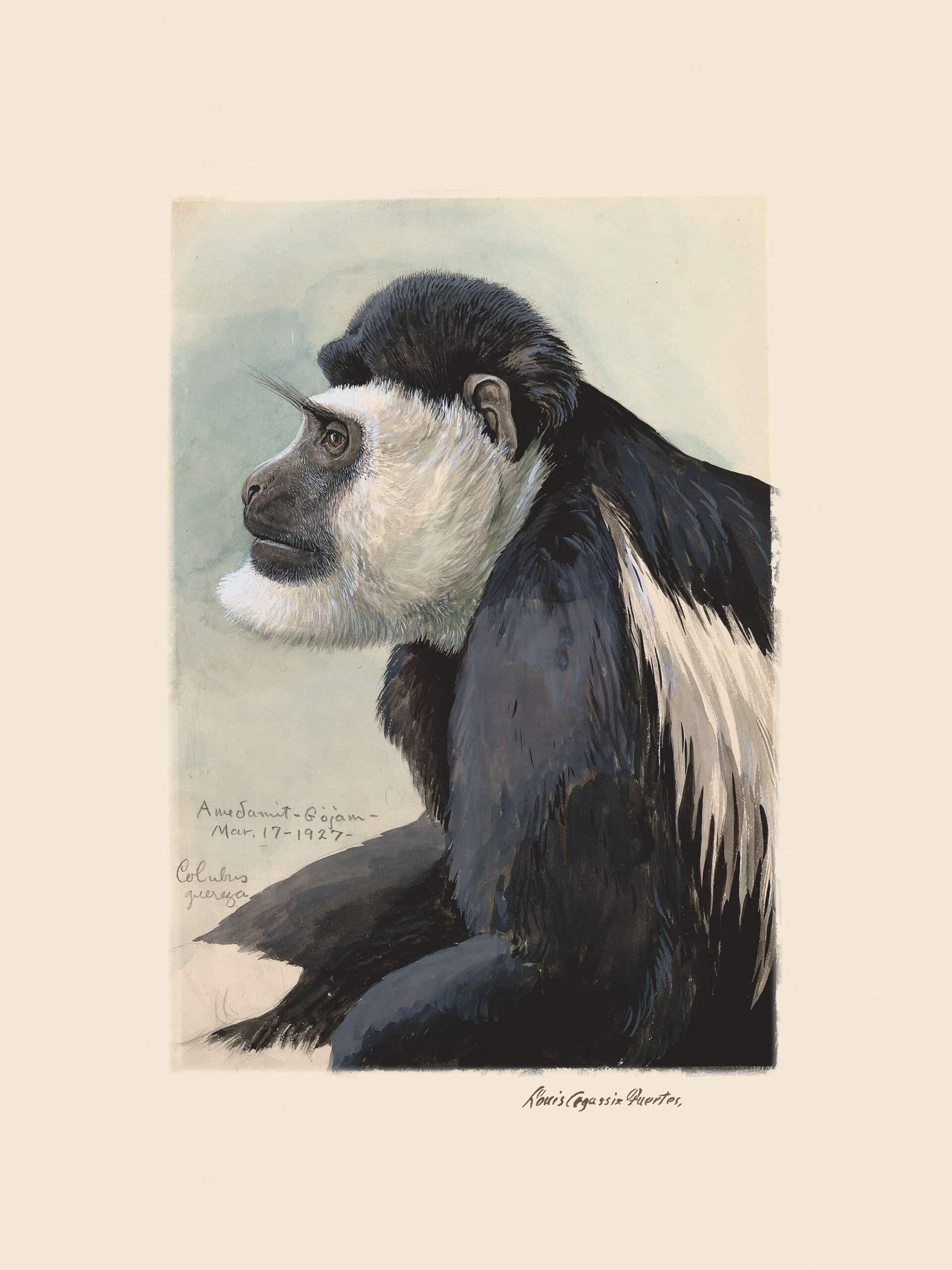

From a technical standpoint Fuertes’s watercolors exhibit a mastery of form, color, and tonality. Often beginning a sketch with graphite, he would then build up the anatomy, movement, and posture of the bird before applying watercolor. Then, once the essential form was captured, Fuertes would focus on the unique tints and shades of the bird’s plumage as he perceived it. The resulting watercolors capture both the 3 dimensionality of the birds as well as the highly detailed texture and design of their plumage. After completing several field sketches of a subject, Fuertes would often use these for reference in a more complete paintings. This can be seen in his watercolor sketch of the Colobus monkey Pl. 109 on the right, and his compositionally developed painting of the Colobus Group Pl. 111 on the left.

Pl. 111, Colobus Group

Louis Agassiz Fuertes

Pl. 109, Colobus Monkey

Louis Agassiz Fuertes

However, the majority of Fuertes’s watercolor sketches would remain in their original field-study form because not weeks after his return from the expedition, Fuertes was killed by a train while driving his car. His paintings, which were with him at the time, survived the collision and were later sold to the Field Museum where they are housed today. The Oppenheimer Field Museum Edition of Fuertes’s Abyssinian Expedition Watercolors makes these unique paintings available outside the rare books repository in a limited edition print run of 500.