Audubon Prints

Interspecific Encounters in Audubon’s Birds of America

Picturing combat between different species in Audubon’s prints.

Table of contents

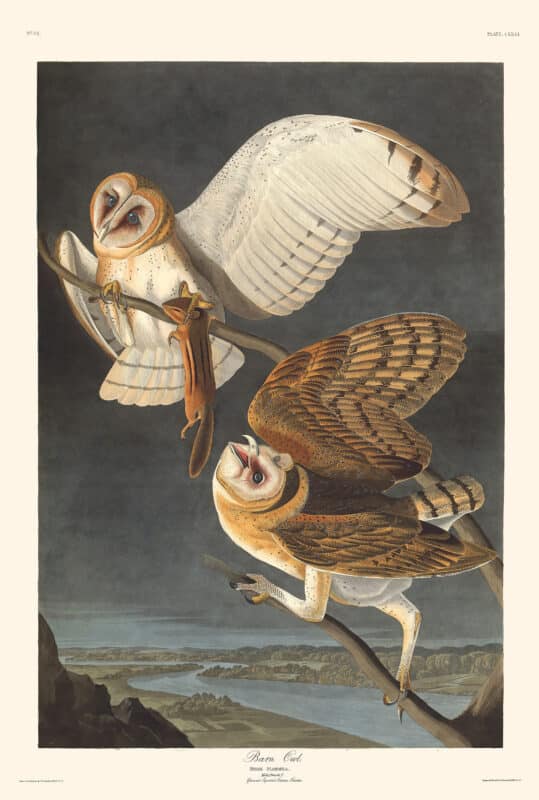

When it comes to capturing both nature’s beauty and its brutality, Audubon does not refrain from detailing either one. Often his prints capture nature as a battlefield in which Barn Owls pin lifeless squirrels in their talons, White-headed Eagles tear at the flesh of marooned catfish, and Great White Herons swallow their catch whole. Such are the laws of nature, and so Audubon renders them with fidelity. What is shown less often in Audubon’s prints are the preceding moments of combat between two species before the fateful denouement. The Common Mocking Bird, octavo pl. 138, and the Ferruginous Mockingbird, octavo Pl. 141 are two unique examples in which interspecies skirmishes are shown with no clear victor or conclusion.

Interspecific Combat

For example, in the Common Mocking Bird, also known as the Northern Mockingbird, we are presented with a scene in which three mockingbirds engage in combat with a monstrous Timber Rattlesnake, who, coiled securely around the trunk of the tree, threatens the stability of the mockingbird’s nest. Surrounded by yellow jasmine flowers, the tetrad fight to defend their verdant abode. Assailing the rattlesnake from every angle, the birds evoke a fluster of anxious indignance as they challenge the intruder. One bird topples off the nest as it recoils from the snake’s advance, another pecks at the reptile’s eye, while the remaining bird stations itself above the turmoil and screech messages of encouragement to its companions below. The interesting thing about this print is that two species are shown in combat with no clear victor. As previously mentioned, this theme is a rarity in Audubon’s work, which often depicts two or more species in the same print for the purpose of visualizing the diet of one which consists of the carcass of the other.

After witnessing the mockingbird-rattlesnake encounter, Audubon writes that “Different species of snakes ascend to [mockingbird’s] nests, and generally suck the eggs or swallow the young; but on all such occasions, not only the pair to which the nest belongs, but many other Mocking-birds from the vicinity, fly to the spot, attack the reptiles, and, in some cases, are so fortunate as either to force them to retreat, or deprive them of life” (Audubon 1831, 108). His recollection of the altercation indicates a positive outcome for the mockingbirds, who, as Audubon recounts, tend to congregate in collective defense of one another’s territory. In fact, when working together, the birds have the ability to overcome and defeat the snake through collective ambush.

Questioning the Accuracy of Audubon’s Imagery

In her detailed analysis of Audubon’s Common Mocking Bird, Suzanne Low indicates that this particular print garnered a skeptical response from Audubon’s contemporaries. In her book A Guide to Audubon’s Birds of America, Low recounts how “Audubon was severely attacked by critics who claimed that rattlesnakes never climbed trees and do not have fangs that curl outward at their tips” (Low 2002, 41). The criticisms aimed at Audubon’s rendering had partial validity since rattlesnake fangs do not curve outward. However, he was correct in his locational depiction of the rattlesnake since they are, on occasion, found in trees.

Audubon 1st Ed. Octavo Pl. 141 Ferruginous Mocking Bird

Hand-colored lithograph, 1839-1844

In the Ferruginous Mocking Bird, sometimes titled the Ferruginous Thrush, we are confronted with a similar scene of dynamism and conflict. Diagonally running through the print is an oak branch upon which the activity of the composition unfolds. On the one hand, we have a Black Snake whose coils encircle the tree, bird’s nest, and a female thrush along with it. To counter his attack, a group of three male thrushes rush to the rescue. Fury and wide-eyed terror characterize the bird’s movements. One savagely pecks at the snake’s flesh, another swoops down in an attempt to deter the creature’s advance, meanwhile the third audaciously positions himself between the attacker and the delicate contents of the nest. All appear to draw courage from their fellow companions and fight with a voracity that exceeds their small size and limited abilities.

While the conclusion of this violent encounter is not disclosed in the print, Audubon does record his witnessing of the event in his Ornithological Biography. He writes: “The birds in the case represented were greatly the sufferers: their nest was upset, their eggs lost, and the life of the female in imminent danger. But the snake was finally conquered, and a jubilee held over its carcass by a crowd of Thrushes and other birds, until the woods resounded with their notes of exultation” (Audubon 1831, 102). Despite their small size and seemingly innocuous abilities, the band of thrushes triumphed over their reptilian attacker.

The Royal Octavo Edition

These octavos, which are titled as such because they are 1/8th of the size of a Royal sheet of paper, were published after the success of Audubon’s Double-Elephant folio. In order to make Birds of America more accessible to a less economically affluent demographic, Audubon initiated a reprint of his monumental work in 1839. The original Havell edition engravings were rendered in miniature by Audubon and his son John Woodhouse through a process called Camera Lucida, which allowed for a reduction in the size of the artwork without loss of fidelity to the original print. They were then lithographically printed by J.T Bowen in Philadelphia and sold on a subscription basis.

Prints such as the Mocking Bird and Ferruginous Mocking Bird are remarkable because they depict two species caught up in a violent encounter with no conclusive outcome. Unlike Audubon’s White-headed Eagle, Havell Ed. Pl. 31, in which two species are shown, one devouring the other, the Common Mocking Bird and Ferruginous Mocking Bird do not present such an overt scenario. Rather, we are encouraged to ponder the prospective outcomes of the events unfolding before our eyes. We are made privy to the culmination of action, rather than a definitive conclusion.