Botanical Art

Plant Mutations in the Botanical Prints of Pierre-Joseph Redouté

A consideration of the artistic rendering of the Tulip Breaking Virus and the phenomenon of Rose Perfoliation in Redouté’s prints.

Table of COntents

Recognized as the royal dessinateur and peintre for three successive French Empresses; Marie-Antoinette, Josephine Bonaparte, and Marie-Amelie, Belgian artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté etched his name into the history of botanical art. Three of his major works, Les Liliacées, Les Roses, and Choix des plus belles fleurs were produced under royal patronage, and focused principally on the imperial gardens in France. His botanical prints, rendered through the innovative technique of stipple engraving, received a fervent welcome and were praised for their soft modulation of forms and delicate coloring.

Marie-Antoinette, after Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun

After 1783, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art.

The Empress Joséphine, by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon

1805, oil on canvas. The Louvre

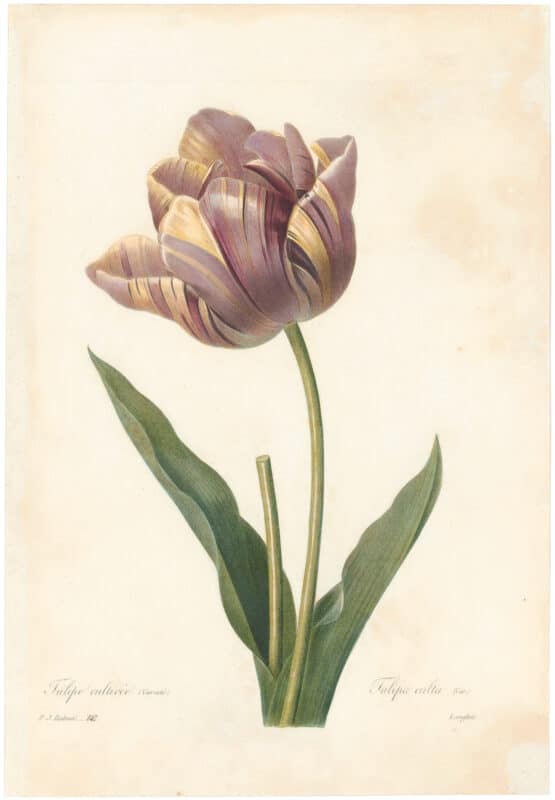

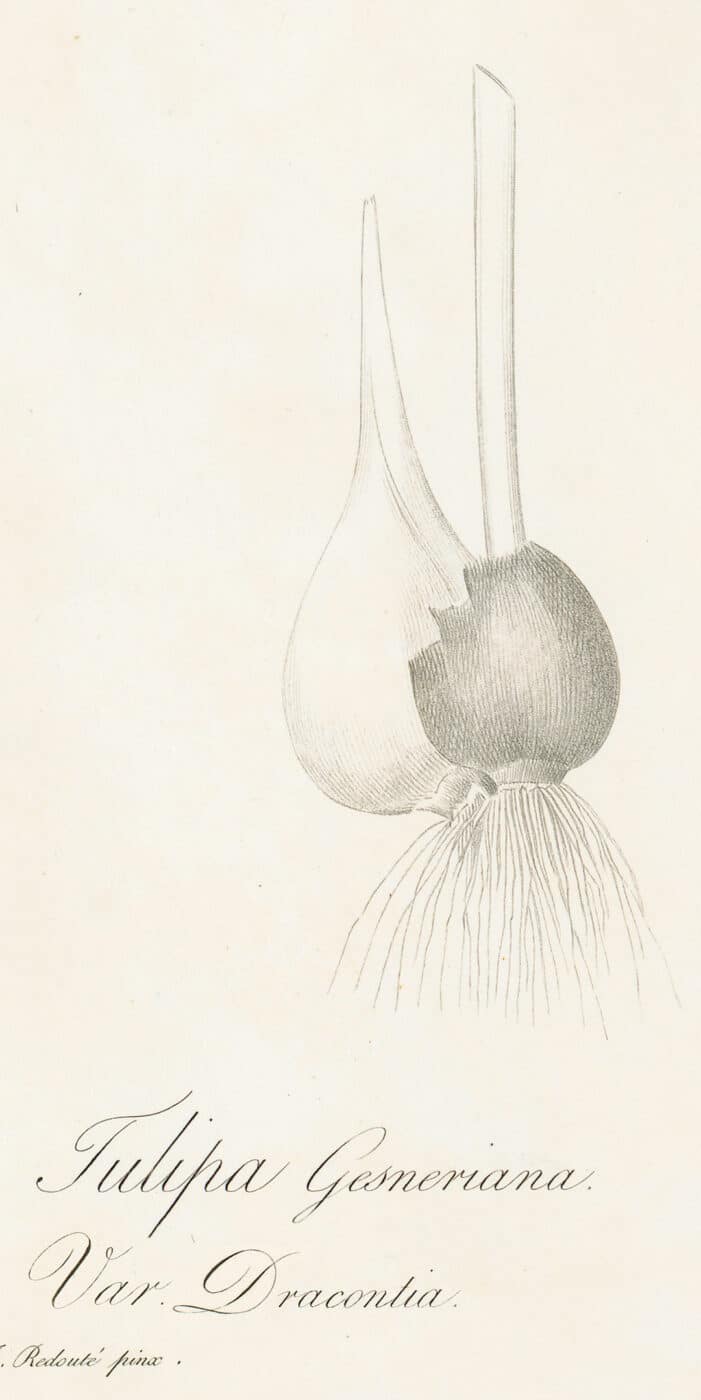

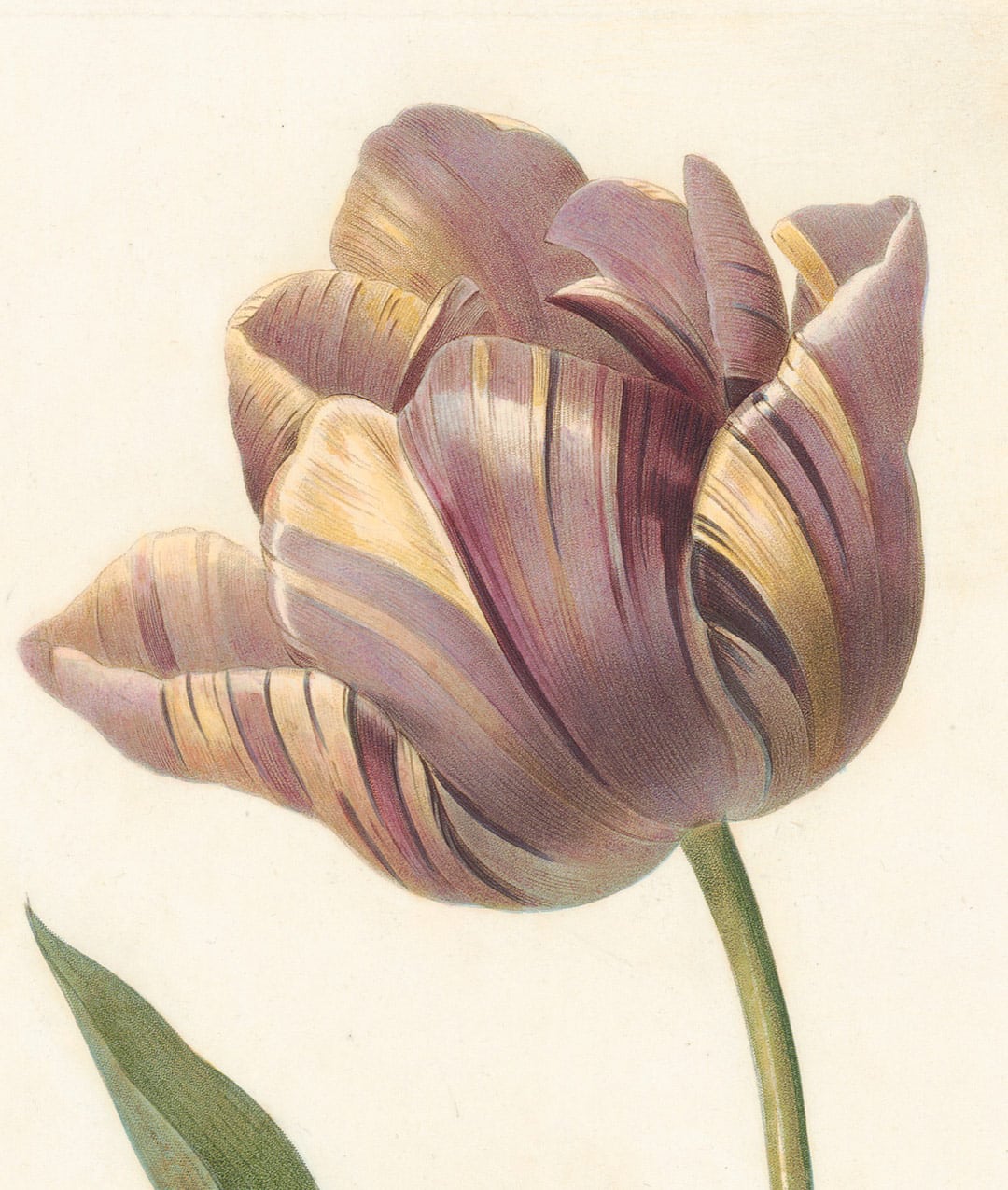

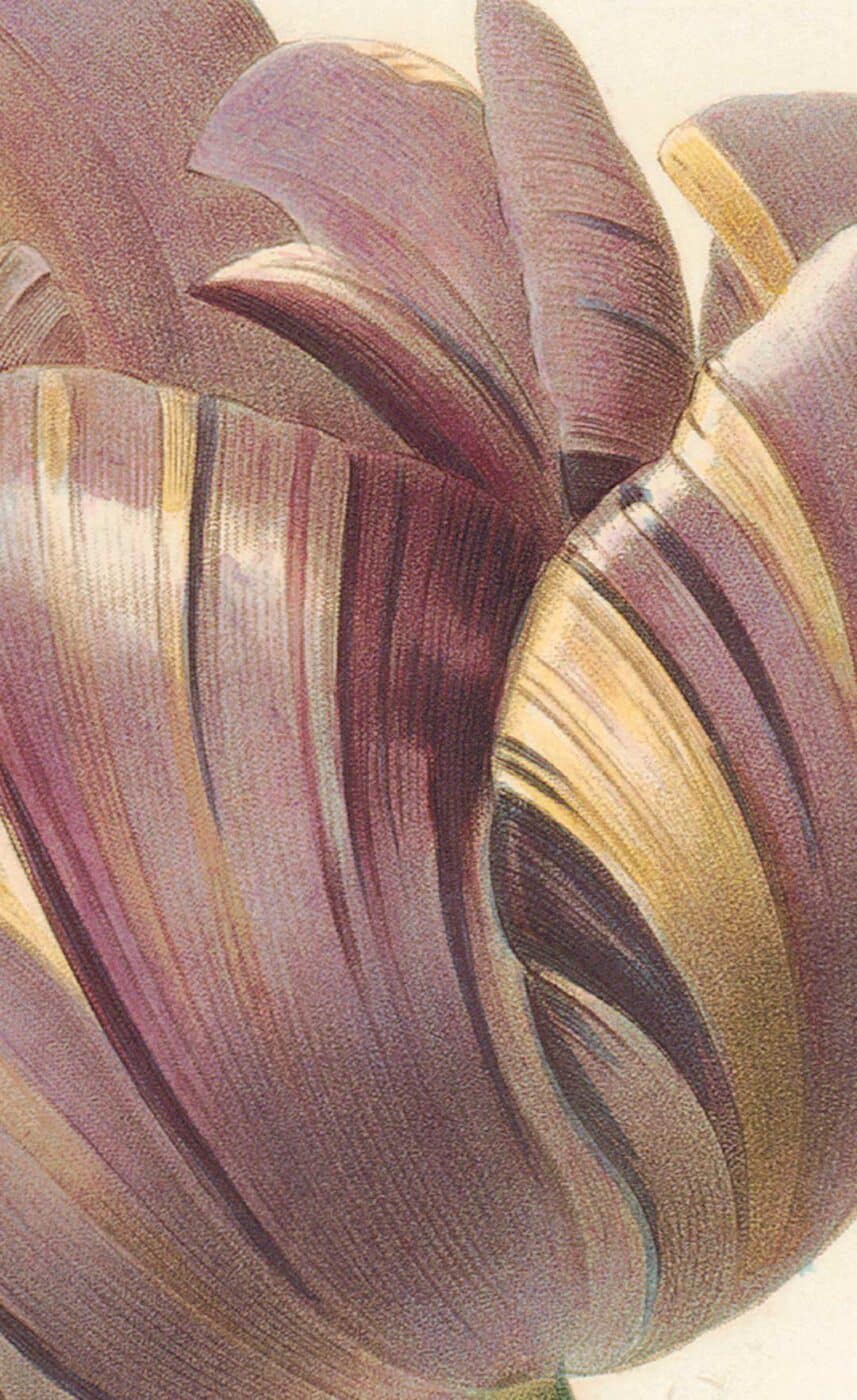

When viewing Redouté’s artwork in sequence, the overall effect is that of a garden encapsulated. Every flower appears to have been cultivated with care and selected as the choicest among the lot. As the titles of his folios indicate, Redouté spent a great deal of time capturing lilies, roses, and the most beautiful flowers, many of which were taken from Empress Josephine’s garden at Malmaison, and later the garden of Napoleon Bonaparte’s subsequent wife, Marie-Amelie. However, among the rows of hundreds of superlative flowers, there are a few examples of morphological aberrations in Redouté’s prints. Namely, the Tulip Breaking Virus, found in Pl. 142 Tulip with pink and yellow streaks from Choix 1835, and Pl. 478 Dracontium-variety of Gesner’s Tulip from Les Liliacees, as well as a phenomenon known as Rose Perfoliation found in Pl. 120 Damask Rose “Celsiana”, and Pl. 137 Variety of French Rose from Les Roses.

Rose Perfoliation

For instance, in the Damask Rose “Celsiana”, Redouté records the botanical mutation of flower perfoliation. Perfoliation, today called proliferation, “is a deformity, whereby the stem continues to grow through the open flower, usually centrally but occasionally to one side” (The Roses, Ed. Lamers-Schutze and Dickmann, 1999, p. 19). This genetic mutation of the rose was unexplainable in Redouté’s time, and has yet to be fully understood today though many suggest that the aberration is caused by continued cell division after the formation of the flower. In Redouté’s print, the foremost flower, which is white and flecked with pink, exhibits a budding stalk that emerges from the center of the fully bloomed flower. In other words, a second flower appears to be growing directly out of the pistil of the former flower, with the thorny stem passing through the center of the rose. This botanical mutation of perfoliation can likewise be seen in Pl. 137 Variety of French Rose where once again a sprouting stem appears to egress from the mature bloom.

Rather than choose a pristine Damask or French Rose to render, Redouté records the aberrant phenomenon as a point of interest and beauty. It is difficult to assume why this was done, but in looking at the collecting habits of his time, it is likely that Redouté rendered the anomalous flower precisely because it was different. In an age where foreign and exotic goods were highly sought after, it is easy to understand why an artist might depict a plant that exhibits unfamiliar and alluring qualities.

Tulip Breaking Virus

As previously mentioned, there are several exhibitions of flowers contaminated with the Tulip Breaking Virus in Redouté’s oeuvre, namely Pl.142 Tulip with pink and yellow streaks from Choix 1835, and Pl. 478 Dracontium-variety of Gesner’s Tulip from Les Liliacees. Tulip Breaking Virus is transmitted by aphids and can be identified by the variegated color of the tulip petals. The viral infection alters the pigments of the tulip on a cellular level and causes the bud to exhibit multicolor patterns often called streaks or flames that “break” the naturally monochrome blossom. (Redoute’s Fairest Flowers, Stearn and Rix, 1987, p. 34) In Tulip with pink and yellow streaks Redouté has captured the color variegation in the tulip’s petals, which exhibit glossy streaks of pale orange and pink. Likewise in the Dracontium-variety of Gesner’s Tulip the lithesome stem curves to support a flaming blossom of densely pigmented yellow and pink feathered petals. A single petal droops away from the rest, emphasizing the dramatic curvature of the flower.

While not fully understood until the 20th century, Tulip Breaking Virus has an extensive and fascinating history centered around 17th-century Holland. These multicolored bulbs became increasingly popular and were sold for enormous sums of money. At its zenith from 1634-37, Tulipmania is best characterized as a speculative frenzy during which the value of variegated tulips soared to unprecedented levels. A notable example of this is the Semper Augustus which was sold for 5,500 guilders, valuing $50,000 in today’s money. By 1637 the bulb market swiftly crashed and left the Dutch economy devastated. Due to the nature of the Tulip Breaking Virus, “The flowers wilt early, leaving behind little energy for the bulbs to use to develop, multiply or blossom. Broken tulips produce fewer bulbs that carry the virus from one generation to the next. And over time without care, the flowers disappear.” (Broken Tulips: ‘That Last Gasp of Beauty Before Death’, New York Times, May 16, 2017, Section D, Page 2). With this dramatic narrative bolstering their identity, the variegated tulips held both aesthetic value and historical intrigue during Redouté’s time.

Technical Process

The flower prints themselves were rendered through a process called stipple engraving, which was still nascent at this time. This technique, coupled with single-plate color printing, allowed Redouté to render incredibly graceful images without the harsh lines characteristic of line engraving. In this process, the artist delineated the images through a series of dots or depressions in the metal plate. As a result, the image was subtly modulated in a manner that suits the soft delicacy of the subject matter. Once engraved, the metal plate was inked with several colors with a muslin cloth or daube through a technique called à la poupée. This process allowed the multicolor print to be rendered in a single run through the press. Lastly, illuminators or colorists would embellish and finalize the print with watercolors.

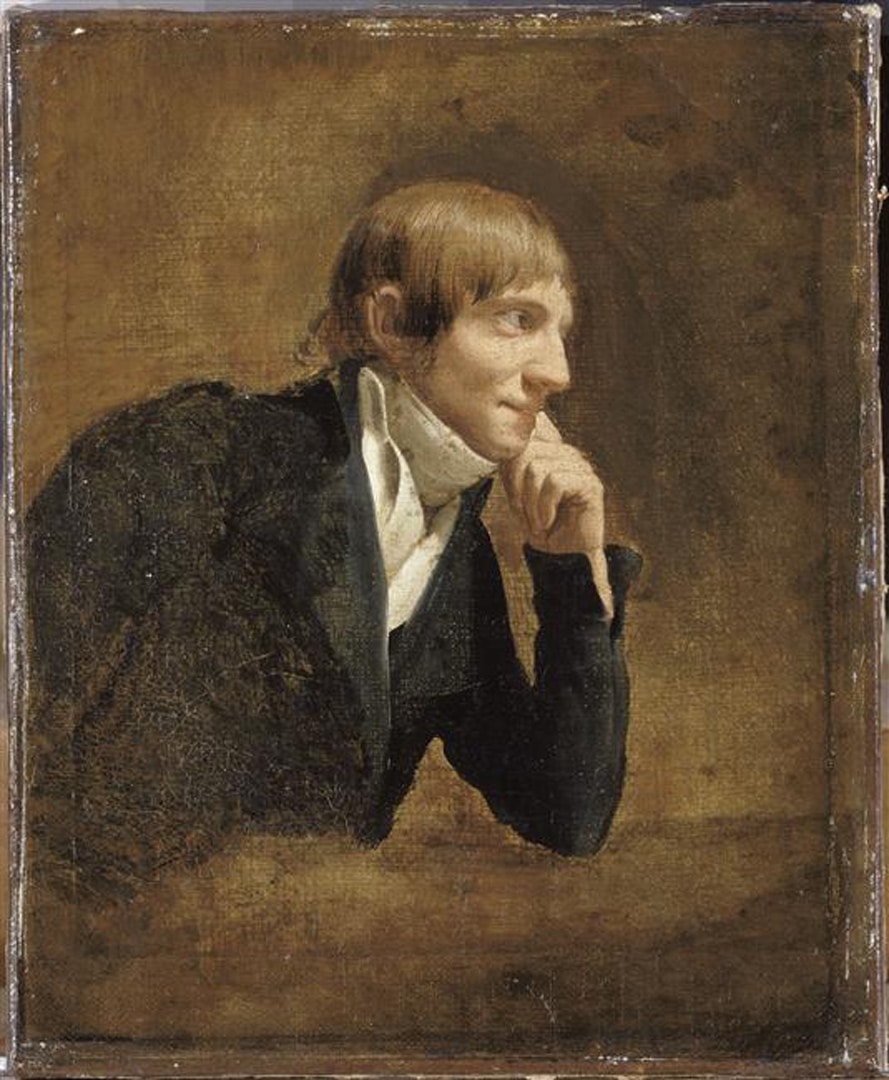

Portrait of Pierre-Joseph Redouté

Painted by Louis-Léopold Boilly, circa 1800

Despite the political tumult that characterizes turn-of-the-century France, from the overthrow of the Bourbon empire, the reign of Napoleon, and the July Revolution of 1830, Redouté continued to methodically produce beautifully serene folios of flowers in stark contrast to his violent historic backdrop. His work was highly respected in his time, and continues to be prized today.

Pingback: Sweet Child of Mine: The Wonder of a Mutant Rose | My Little Spacebook