Birds and Animal Art

The Articulation of Macabre Bird Habits in John Gould’s Prints

Exposing the unsavory tendencies of the Common Cuckoo and Great Grey Shrike in Gould’s Birds of Great Britain.

Table of contents

Renowned for having a prolific publishing career, John Gould issued several thousand prints throughout his lifetime. The magnitude of his creative enterprise was achievable because Gould himself was a master delegator who enlisted numerous draftsmen, printmakers, and specimen collectors to cooperatively contribute to his overall vision.

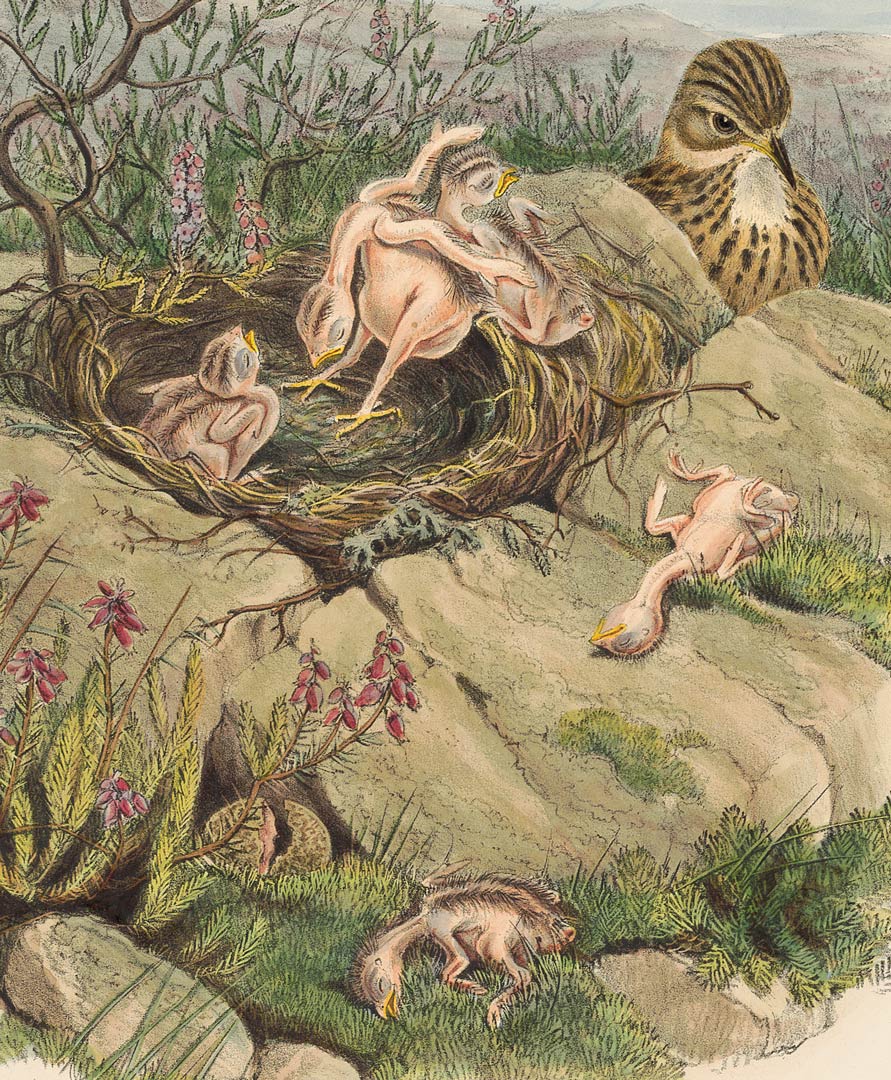

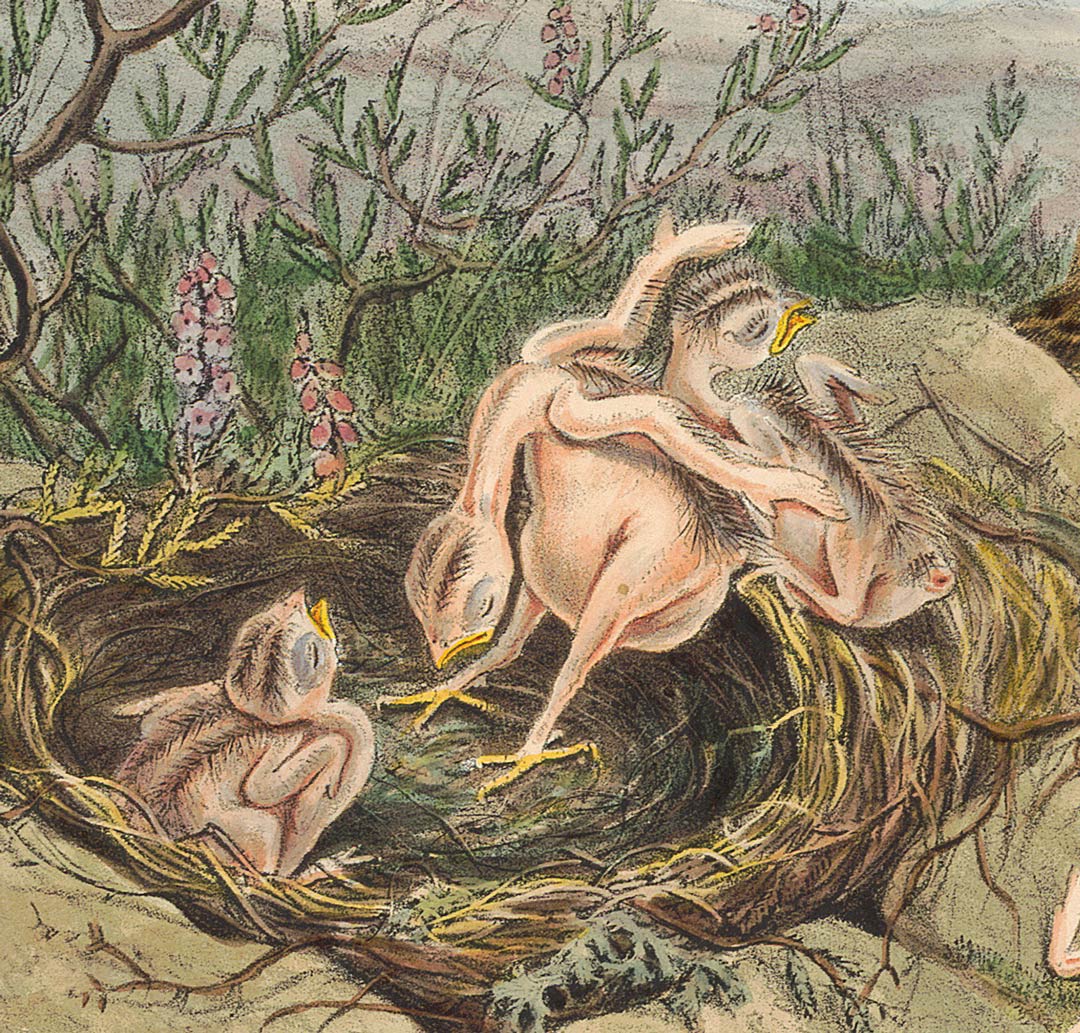

Notable among his published works is his Birds of Great Britain. This folio is unique among his oeuvres because of the increasingly narrative nature of his compositions, which expand to include a greater number of depictions of nests, eggs, and infant avifauna, that in turn, lend his scenes and subjects a sense of chronology and narrative progression from young to mature bird. Additionally, we are provided with a particularly thorough illustration of the bird’s habits, environments, and diets. Among the delightful plates of lusciously colored feathers and delicately articulated wingtips, two prints stand out as being somewhat troubling. These prints are the Common Cuckoo Pl 183 and the Great Grey Shrike Pl 50, in which we are reminded of nature’s brutality.

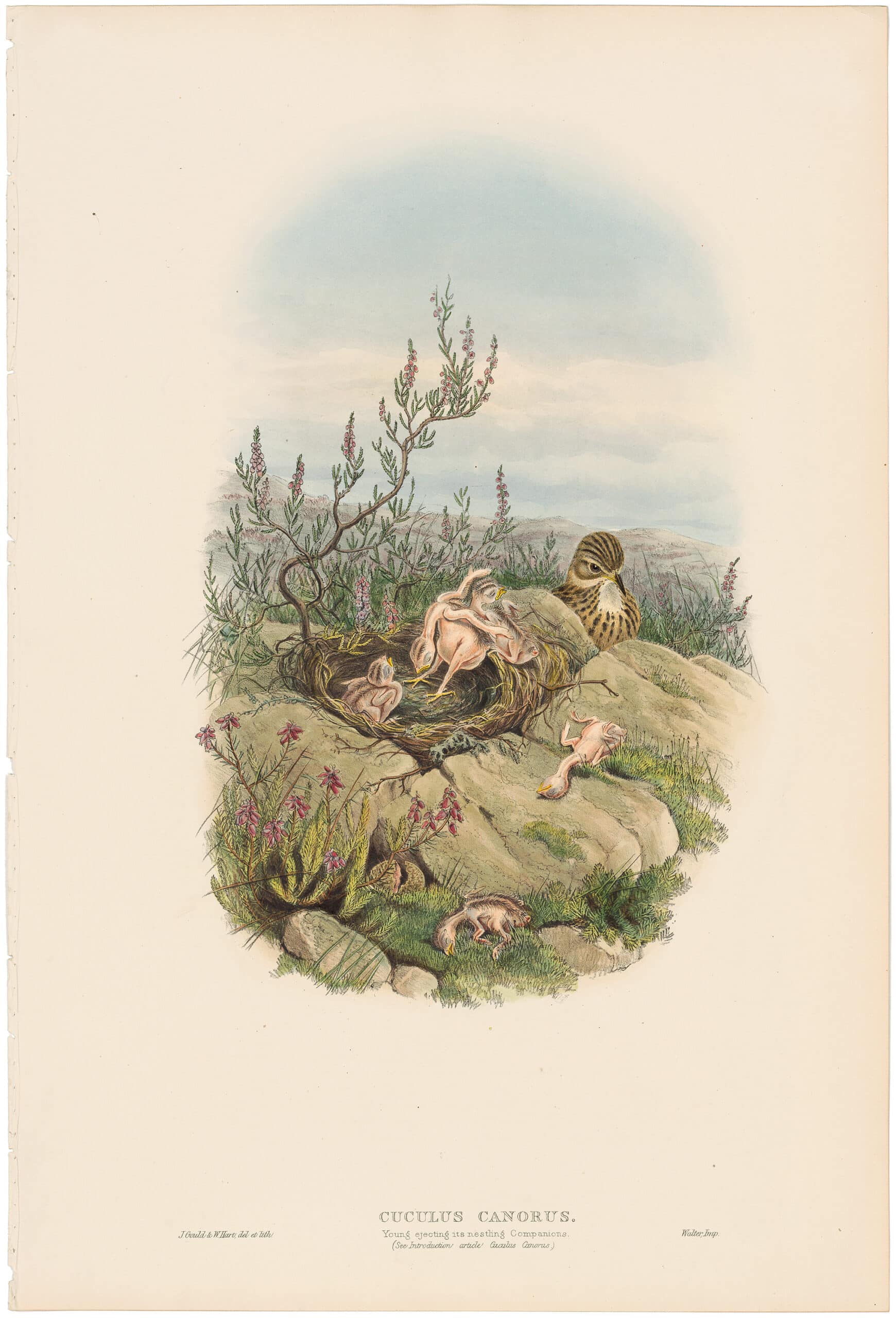

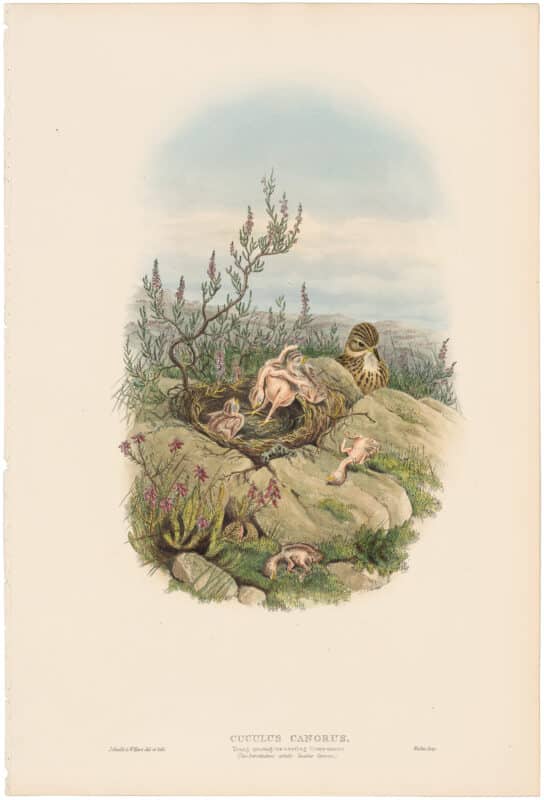

Pl. 183, Cuckoo (young ejecting infant Titlark)

Gould Birds of Great Britain

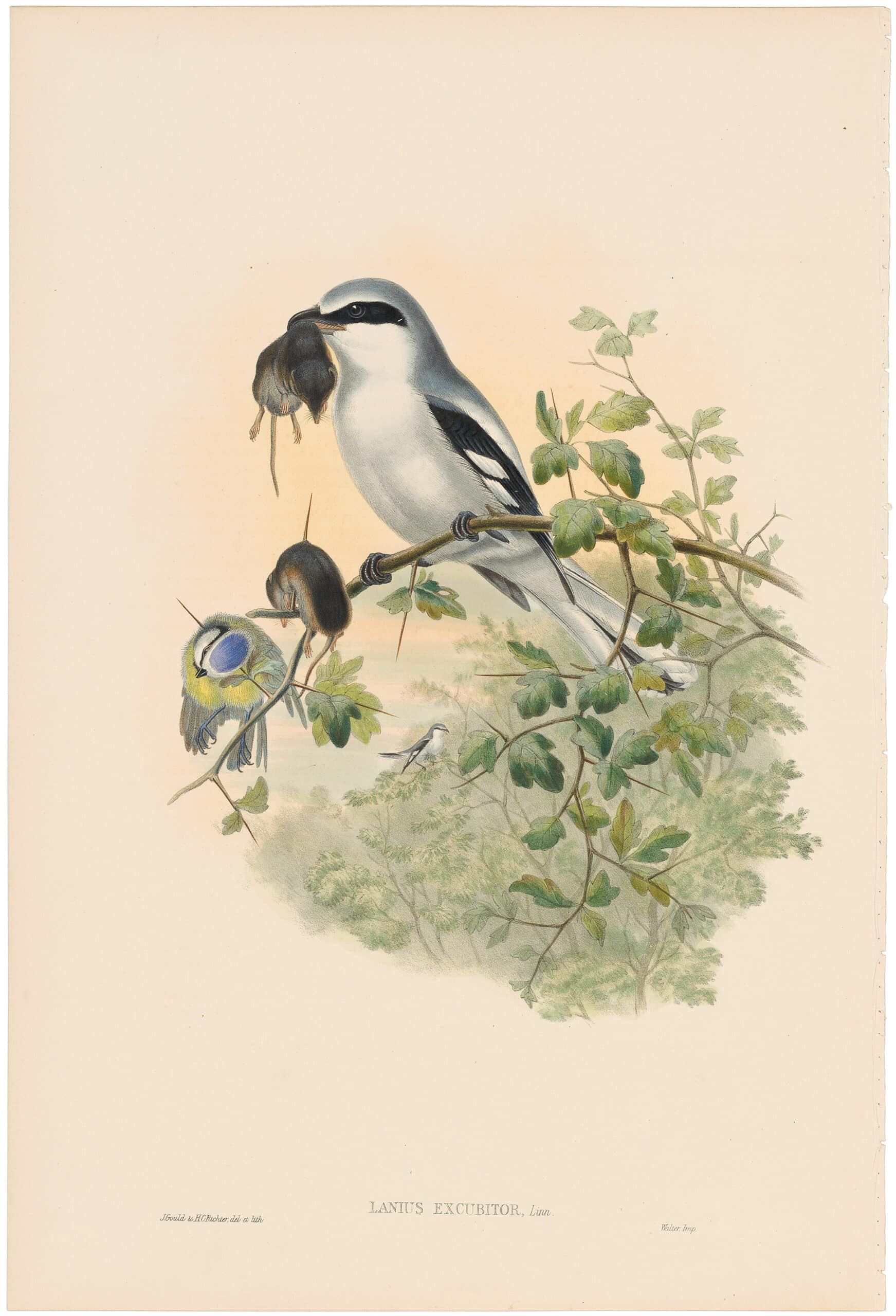

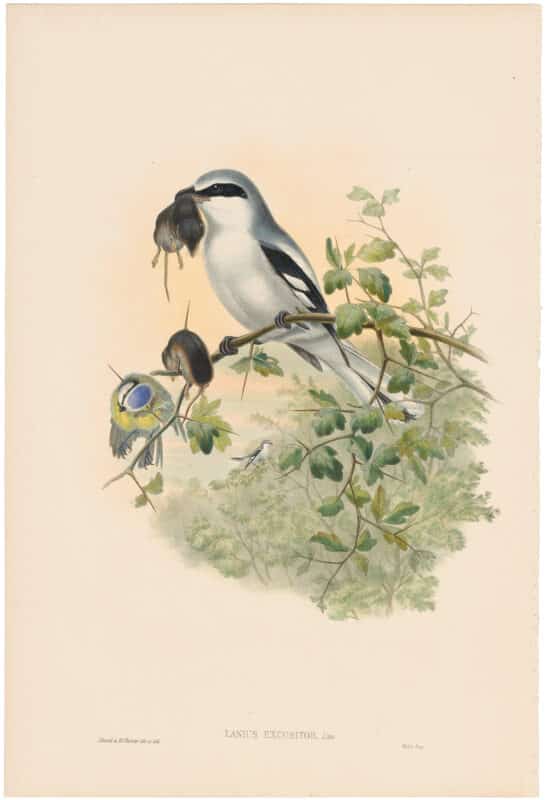

Pl. 50, Great Grey Shrike

Gould Birds of Great Britain

Common Cuckoo

Upon first glance, the Common Cuckoo or Cuculus Canorus is first and foremost a bewildering impression. Here we are greeted with what initially appears to be a scene of domesticity; a small nest huddled amongst an assortment of mossy rocks in which several fledglings are housed and protectively surveyed by a mature bird close by. However, several of the small fleshy fledglings are in active tumble out of the protective haven of the nest. In fact, one of the fledgling, the largest amongst them, is voluntarily expelling the others from the nest. This would be our Common Cuckoo. The reckless abandon of the cuckoo could be considered a hereditary trait since the young, while still an egg, is laid by the mother bird in the nest of another species, often that of a wren, warbler or pipit, after which the begetter then leaves the egg and ventures off on holiday to the African continent. When the fugitive egg hatches in the host’s nest, it then proceeds to defenestrate the native fledglings from their nest, as is shown in Gould’s lithograph, in order to optimize its accessibility to the food source and to eliminate its competition. This scarcity mindset ultimately results in the demise of the host-bird’s brood.

In his early years Gould did not believe that the Cuckoo fledgling would have the strength to eject it’s adoptive siblings from the nest, but the keen observations of Mrs. Hugh Blackburn convinced Gould to reconsider his doubt. In his introduction to Birds of Great Britain, Gould recounts his reformed opinion:

“I now find that the opinion ventured in my account of this species as to the impossibility of the young Cuckoo ejecting the young of its foster-parents at the early age of three or four us erroneous; for a lady of undoubted veracity and considerable ability as an observer of nature and as an artist has actually seen the act performed, and has illustrated her statement of the fact by a sketch taken at the time, a tracing of which has been kindly send me by the Duke of Argyll, and I have considered it of sufficient interest to reproduce here as a woodcut.”

(xcii-xciii) Birds of Great Britain

The aforementioned woodcut by Mrs. Hugh Blackburn, pictured to the right, acts as a blueprint for Gould’s rendering of the bird. This practice of outsourcing sketches, observations, and the collection of specimens was routine in Gould’s production enterprise. While he himself would often orchestrate the preliminary sketch, his draftsmen, lithographers, and colorists were largely responsible for bringing his ideas into fruition.

Great Grey Shrike

In addition to recording the rather disturbing conduct of the cuckoo, Gould likewise captures the gruesome habits of the Great Grey Shrike or Lanius Excubitor. In this print we are confronted with a male shrike in the process of adding a shrew mouse to its victual reserve, where, to the left, the bird’s ample pantry accommodates yet another mouse and a small bird. The shrike, defiantly posed on it’s perch, appears not unlike a masked assassin with it’s dark facial plumage. This bird is known to be cunning and “sometimes sing(s) another bird’s song to lure unsuspecting victims into a deceitful ambush” (“Beware the Great Grey Shrike: The pretty songbird with the temperament of Vlad the Impaler,” Country Life, March 29, 2018). In fact, a look into the etymology of the bird’s scientific nomenclature portents its aggressive habits since Lanius aptly translates as butcher. The shrike, like the cuckoo, is here to remind us that nature operates unto a system of it’s own with no regard for our speculative and moralistic opinions.

As previously mentioned, Gould was an incredibly prolific creator who orchestrated the production of “publications on the birds and animals of three continents, monographs on toucans, trogons, and humming-birds, illustrations to two ships’ voyages, and about three hundred scientific articles and papers” (John Gould’s Birds of Great Britain, Maureen Lambourne, 7). With the aid of H.C. Ritcher, William Hart, and Joseph Wolf, Birds of Great Britain was issued in 5 parts from 1862-73. Containing 367 plates, this folio was one of Gould’s latter publications and indicates a well developed narrative structure within its compositions.

We can see the evolution of Gould’s narrative structure when comparing his illustration of the Great Grey Shrike and the Common Cuckoo for Birds of Great Britain with those of the same species captured several years earlier in his survey of the Birds of Europe (c. 1833). Below is a comparison of the Great Grey Shrike Pl. 67 from Gould’s Birds of Europe on the left, and the same species from his Birds of Great Britain on the right. Here we can see that in the latter print Gould has incorporated a greater degree of environmental elements to visualize the birds habitat and diet.

Similarly, when comparing Gould’s depictions of the Common Cuckoo from both his Birds of Europe (left) and Birds of Great Britain (right), we see the same tendencies reiterated. In the former print, mature male and female cuckoos are shown balancing on a bough. While there is some dynamism to the composition of the print, it does not elicit the same compelling narrative as the latter cuckoo print. Rather, in the former we are presented with the isolated specimens, whereas in the latter we are given a glimpse of the strange and abhorrent habits of cuckoo fledglings.

Rendered through lithography, these prints retain an ambient, feathered quality characteristic of the medium and appropriate for the subject matter. Gould’s prints were received with enthusiasm and “Among his list of subscribers, Gould could boast of monarchs, royal highnesses, dukes and duchesses, marquises, earls, counts barons and lords” (Bird Illustrators, 52). As an innovator and shrewd businessman, Gould was able to conduct an impressive production enterprise for a number of decades until his death in 1881.