Botanical Art

The Historical Significance of Botanical Illustration

A consideration of the motives behind picturing plants including the functional uses and theoretical implications of floral imagery

Behind the apparent whimsy and charm of botanical illustrations, there lies a broad and complex history of scientific innovation, social relations, and political expansion. The representation of plants throughout time has served a multitude of purposes including both functional and decorative uses. The advent of botany begins with the visual cataloging of plants and herbs for pharmacological purposes to aid users in identifying specimens for their medicinal value.

Likewise, in Early Modern Europe, as empires expanded, this collecting and cataloging impulse continued but with the intention of importing, naming, and placing the foreign plants within a European taxonomy. Additionally, during the Victorian era, botanicals served as a modest and respectable subject matter for female artists to pursue. Moreover, botanical studies and florilegium folios provided artisans with extensive reservoirs of reference material to use in their applied arts. As a result, today we are left with centuries of botanical prints that offer not only glimpses of the trajectory of botany and printing technologies, but also the social and political implications of plants.

Beginning with artist Basilius Besler, whose monumental florilegium Hortus Eystettensis dates back to 1613, we are presented with an early example of flower illustrations that prioritize the beauty of the plant over its usefulness. This characteristic of the folio departs from earlier representations of plants that were made to record the medicinal use of the plant such as the above German woodcut of a carrot from circa 1600 in which we see the primacy of text over the rudimentary image. In contrast, Besler’s florilegium elevates the plants as objects of beauty as shown below.

However, Besler’s folio does maintain remnants of this earlier practice through his emphasis on the roots of plants. Take for instance Besler’s Deluxe Ed. Pl. 110, Broomrape, Water hemlock, Branched bur-reed in which the fibrous root and bulb of each plant are purposefully articulated. Likewise in Besler’s Deluxe Ed. Pl. 172, Dark violet columbine, White columbine, et al, he has taken special care to include the root of the central violet columbine by featuring it as a detached fragment below the stem of the flower.

In his book Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration, Gill Saunders explains how “Roots and underground parts of plants were often of medical value to the herbalist and the apothecary, and knowing this, the artist illustrating a herbal invariably gives them as part of his account of the plant” (Saunders 1995, 14). In addition to the history of visual representations of plants with a focus on their medicinal value, as an apothecary, Besler has a professional interest in the pharmacological aspects of the plants.

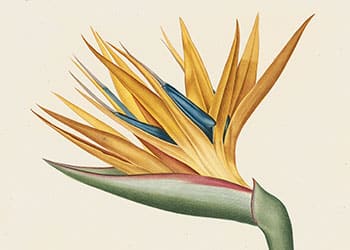

As previously mentioned, in addition to retaining the medical understanding of the plants, Besler’s florilegium was also an unabashed tribute to the beauty of the garden at Eichstätt, and the grandeur of its owner, Johann Konrad von Gemmingen, the Prince Bishop of Eichstätt. During the 17th century “plants and gardens became status symbols, and exotic ornamental plants themselves became part of a much wider trade in luxurious commodities” (Saunders 1995, 72). As a flood of exotic and ornamental plants reached European docks, the ownership of such plants acted as a visual attestation to the impressive reach of the respective empire. Consequently, gardens became battlefields upon which political expansion was asserted through the acquisition and naturalization of foreign plants.

Much like Besler’s cataloging of the Prince-Bishop’s garden, Pierre-Joseph Redouté likewise recorded the impressive contents of several French imperial gardens including those cultivated by Queen of France Marie-Antoinette, Empress Josephine, and Napoleon’s second wife Marie-Amelie. The royal gardens from which Redouté drew reflected not only the refined taste of the individual empress who cherished them but also the broader geographical reach of the reigning regime. Plants from all over the known world were cultivated in the imperial gardens as a visual manifestation of cultured personal taste and expansive political power.

Take for example Redouté’s Pl. 456, Cultivated Ananas and Pl. 444, Eating Banana from his folio Les Liliacées. Pineapples were among the exotic fruits brought to Europe from the tropical climates of Central and South America. Likewise, Bananas are native to South East Asia, India, and Northern Australia and were subsequently brought to Europe and America as a result of the increasingly globalized networks of trade. As a result, the appearance of certain plants in European artwork directly correlates to the reach of the respective empire.

In contrast to Besler, Redouté was born after a standardized system of plant classification was instated following the initiative of Carl Linneaus. Rather than categorize plants by their medicinal uses, Linnaeus introduced a system of classification that relied on the flower and its reproductive organs, the stamen and pistils, for identification and categorization. Consequently and in the wake of Linneaus, we can discern “an increased focus on the stamen, and pistils in later botanical illustrations.”

Take for example Redouté’s Lilies Pl. 366, Dalmation Iris in which the freshly cut flower is shown as a lone specimen, with a small diagram of dissection to the lower left quadrant of the print. Sanders enumerates Redouté’s creative decision by detailing how “It fulfills the Linnean criteria perfectly, and has no need of a more comprehensive representation, so no indication of habit of growth, no root or bulb, no seeds” (Saunders 1995, 96). In contrast to Besler’s intentional inclusion of roots and bulbs, Redouté’s truncation of the plant and heightened focus on the interior structure of the flower elucidate the development of botany as a scientific discipline independent from the study of medicine.

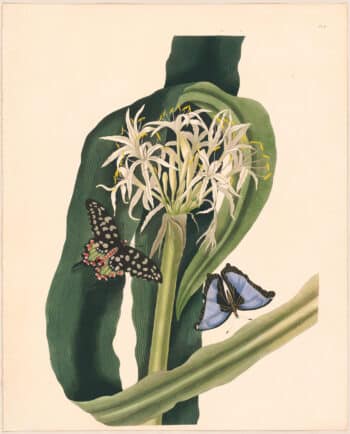

The Linnean influence can also be found in the work of Priscilla Susan Bury whose A Selection of Hexandrian Plants, Belonging to the Natural Orders Amaryllidae and Liliacae directly references the stamen as an elemental classificatory attribute. The term Hexandrian denotes plants possessing six stamens, such as lilies and amaryllises, and was used as a creative parameter for Bury’s folio. In her hand-colored engraving Pl. 46, Amaryllis Johnsoni-Solandriflora, the flower’s delicate anthers and filaments are assertively exposed leaving no doubt about their taxonomic significance.

Pl. 46 Amaryllis Johnsoni Solandriflora

Priscilla Susan Bury

Growing up in a well-off family in Victorian England, Bury was surrounded by the imported plants from her family’s gardens and greenhouses. Resultantly, Bury directed her creative tendencies toward rendering flower portraits. However, there were other social forces at play that directed a Victorian woman’s creativity towards rendering plants as it was one of the select few subject matters deemed suitable for a woman to draw.

In the introduction to the 1756 edition of The Delights of Flower Painting, the anonymous author describes the art of illustrating flowers as “a genteel, diverting and instructive study [so] that the fair sex could find amusement by the filling up of those tedious hours that would otherwise lie heavy in their hands” (Jack Kramer, Women of Flowers, 1996, 21). This disparaging statement sheds light on the circumstances in which female artists lived and worked in the 19th century, and causes one to wonder what else they might have produced had they been granted unbridled creativity. Moreover, the presence of these social and professional constraints makes it all the more impressive that Bury’s folio was indeed published.

In conclusion, plant portraits offer us a unique and subtle opportunity to look into the circumstances of the past beyond the development of natural history to trace the unfolding of scientific, sociological, and political history as well. Folios such as Basilius Besler’s monumental Hortus Eystettensis act as a transitional fulcrum between the association of plants as medicine to plants as objects of beauty. Similarly, Redouté’s Les Liliacées, Les Roses, and Choix des plus belles fleurs remind us of the political connotations of imported exotic plants found in the French imperial gardens. Lastly, the botanical prints by Priscilla Susan Bury remind us of the sociological tenor of plant illustration in Victorian England and the cultural landscape that female artists were challenged to navigate. Though delightful and seemingly frivolous to behold, botanical art has its roots in a much broader framework of intersecting disciplines and historical circumstances.