Botanical Art

The Symbolic Implications of the Pineapple

An examination of the representation of pineapples as luxury commodities in the art of Merian, Redouté, and Brookshaw

Visually flamboyant, gustatorily delicious, and polarizing when placed on pizza, the pineapple is a fruit ripe with symbolism and dynamic historical consequence. From its introduction to the European continent in the 15th century, the exotic imported fruit swiftly gained recognition as a luxury commodity exclusive to the upper classes and could often be found poised as a centerpiece at lavish parties. As a result, it became a poignant metaphor for affluence, effusive hospitality, and refined taste.

By the 18th century, horticulturists had figured out how to grow the tropical fruit in the controlled environment afforded by hothouses, and thus it lost some of its exclusive appeal. However, it remained a proud staple in the gardens and greenhouses of the gentry well into the 19th century. By tracing the representation of the pineapple in the art of Maria Sibylla Merian, Pierre-Joseph Redouté, and George Brookshaw, we are able to better understand the dynamic symbolism of the fruit from the 17th to mid-19th centuries.

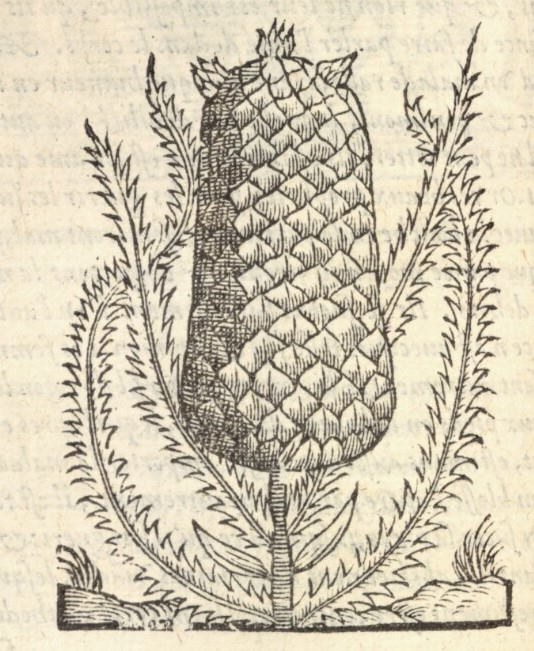

As previously mentioned, the pineapple was first introduced to Europeans in 1493 by Christopher Columbus who encountered the prickly bromeliad during his second expedition to the New World. While on the island of Santa Maria de Guadeloupe de Extremadura, he was presented with the fruit by the native Arawak people who consumed it as a staple of their diet. The fruit swiftly gained traction with the European nobility after King Ferdinand of Spain declared it to be his favorite. However, it was two centuries before European horticulturists were able to successfully create the controlled environment necessary for the fruit to flourish. Instead, the pineapple enthusiasts of Early Modern Europe had to rely on imported fruits to satisfy their expensive tastes. Consequently, from its introduction to European soil until the late 17th century, the fruit was recognized as a delicacy exclusive to the wealthy.

Living during the 17th-18th centuries, Maria Sibylla Merian captures the fruit at a time when it was still largely inaccessible to the common person. In her folio Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, or Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname, Merian represents two pineapples. Featured as Plate 1 and 2 in her folio, Merian catered to the high-end tastes of the aristocracy through the prominent placement of the fruit and lent her book an air of sophistication and foreign intrigue. Such fruits were not widely available even in port towns like Amsterdam where Merian lived. In fact, most viewers of Merian’s prints would be encountering the fruit for the first time through her artwork.

Pl. 1 Pineapple Plant

Maria Sibylla Merian

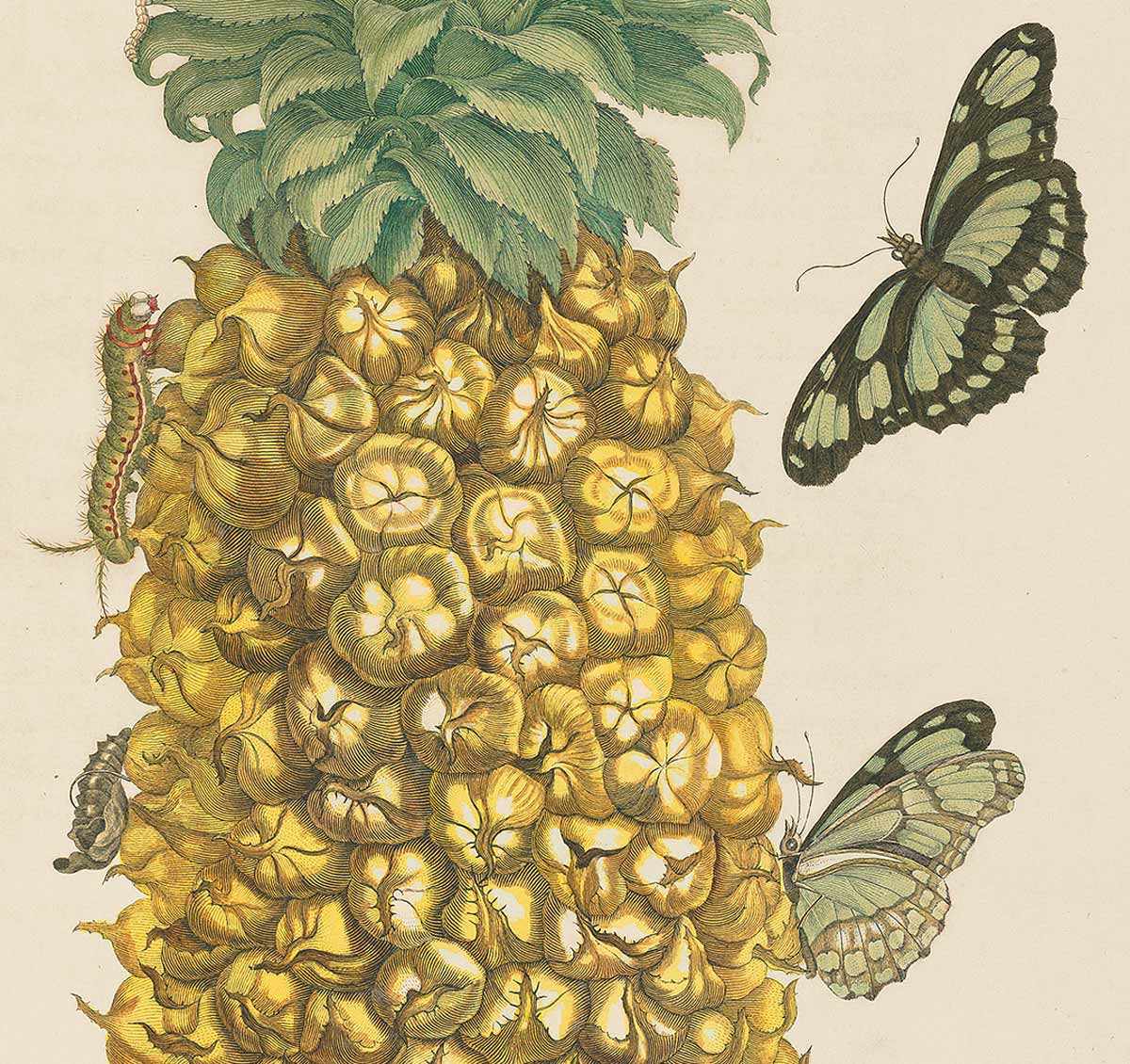

Pl. 2 Pineapple

Maria Sibylla Merian

Let us now compare the two pineapple prints. Pl. 1 Pineapple Plant portrays the immature fruit growing from its bristly stalk and surrounded by two types of cockroaches. The print is visually dynamic and engaging as the vibrant red hues of the spiky pineapple leaves reach out like threatening tendrils. Likewise, the texture of the fibrous plant itself satiates the viewer’s desire for animated detail. Lastly, the two species of cockroaches encircle the plant in various stages of metamorphosis.

In contrast, Merian’s Pl. 2 Pineapple depicts the fruit shorn from its stem and at peak ripeness. The vibrant coloring and engorged flesh of the pineapple present the fruit for our visual delectation. Likewise, cochineals, ladybugs, and butterflies in various states of maturation adorn the fruit. Unlike Pl. 1 in which the immature pineapple appears almost aggressive with its spikey leaves, sinuous tendrils, and cockroach inhabitants, Pl. 2 captures an enticing interpretation of the fruit. Moreover, the presence of the butterflies, ladybugs, and perhaps most significantly the cochineal, reinforces the inviting nature and exclusionary caliber of the pineapple. It is significant to note that cochineal was the single most expensive dye imported from the Americas to Europe from the 16th-19th centuries (Marichal, 2014, “Mexican Cochineal and European Demand for a Luxury Dye, 1550–1850”). Thus the material associations of cochineal and pineapple work to reinforce the mutual luxury status of both imports.

Authors Megan Baumhammer and Claire Kennedy in their chapter “Merian and the Pineapple: Visual Representation of the Senses” suggest that “The pineapple, for Merian’s early modern European audience, was an exotic, luxurious fruit, embodying the riches and seductions of the New World and the colonial territories across the Atlantic. Like the colonies, the fruit was largely inaccessible in Europe, and the lush presentation of the pineapple is the means by which the readers of the Metamorphosis were able to overcome the obstacle of distance, not just through an artefact of vicarious observation, but through a much more encompassing sensorial experience” (Baumhammer and Kennedy, 2017, 191).

By engaging with the viewer’s ability to tap into the phenomenological experience of perceiving, smelling, touching, and tasting the fruit, Merian’s depictions of the pineapple allow the viewer to be transported from their geographical and social relegation to the exotic realm of Dutch Suriname and to the realm of the elite. Moreover, it is significant to note that in the context of Merian’s Metamorphosis, these two plates are unique in that they visually prioritize the fruit over the metamorphosis of the insects which was the focus of her life’s work. Even the studious entomologist could not escape the thralls of the sensuous pineapple.

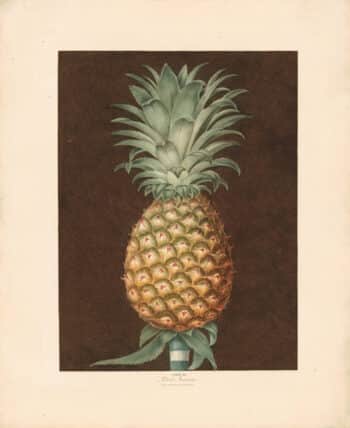

Pl. 455, Cultivated Ananas

Pierre-Joseph Redoute

Pl. 456, Cultivated Ananas (Detail)

Pierre-Joseph Redoute

Working nearly a century later in France, Pierre-Joseph Redouté depicts the same pomological subject in similar compositions to those of Merian. Take for instance Pl. 455, Cultivated Ananas, and Pl. 456, Cultivated Ananas (Detail) from his folio Les Liliacées. In the former print, we see a small green pineapple emerging from a sea of prickly leaves. In the latter print, we see the fully mature pineapple crowned with green leaves and supported by a single stalk. These prints were rendered after the contents of Empress Josephine’s gardens at Malmaison, and therefore hold connotations of royal exclusivity.

In fact, pineapple motifs were used throughout Europe and America to adorn countless decorative objects, utilitarian instruments, and architectural edifices in order to instill in them an air of sophistication. Take for example the above pictured 17th-century German cup that is fashioned after the prickly fruit. Wrought of silver and selectively gilded, the precious materiality of the cup itself reinforces the dignity of the pineapple. Likewise, the grand Pineapple feature in Dunmore Park in Scotland reaffirms the pervasive notoriety of the fruit as seen below.

Similarly in America, Charleston’s Pineapple Fountain, constructed in 1990, is a welcome sight to be found along the waterfront and harkens back to the fruit’s association with hospitality.

George Brookshaw’s Pomona Britannica likewise included two varieties of pineapple amongst his Most Esteemed Fruits. Brookshaw’s folio not only captured the contents of the gardens at Hampton Court and the important gardens on the outskirts of London, it also attempted to introduce these varieties of fruit to country gentlemen so that they might be further cultivated. As a result, his prints not only reflect the existing tastes of the upper classes but also project these affections onto his audience by visually propagating the fruit.

Take for example Pl. 40, Black Jamaica, and Pl. 43, Brown Havannah in which we are presented with a single pineapple poised against a dark stoic background. In each print, the fruit occupies the entire composition with all focus lent to it. In the context of Brookshaw’s work, this is not uncommon but more often than not he combines several types of fruit in one print. Therefore, we can deduce that the pineapple commands its own composition not only because of its size but also because of its prestige. Moreover, the titles of the prints evoke the feeling of far-off lands abundant with exotic mystery and intrigue.

In conclusion, the pineapple is far more than a common garnish for your poolside drink, or an addition to your ambrosia salad. Rather, the noble fruit holds within its prickly fortress a panoply of grand implications and historical anecdotes. Examining the pineapple through the refracted lens of art, architecture, and material culture allows us to imagine with greater appreciation the bygone status of the tropical fruit.

To see additional works of art by Merian, Redouté, and Brookshaw, please visit the links below.