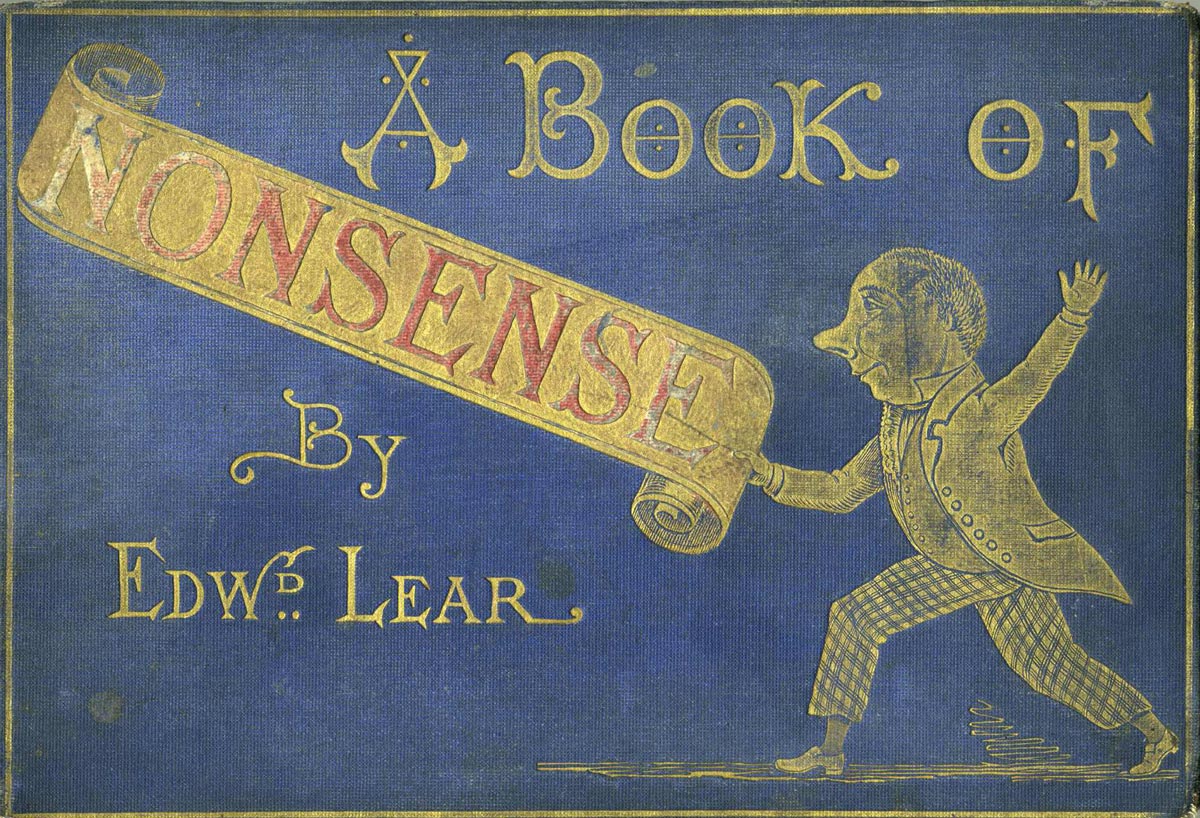

Birds and Animal Art

The Interconnection between Rationality and Nonsense in Edward Lear’s Artwork

A consideration of the relationship between Lear’s scientific illustrations and Nonsense-verse caricatures.

Table of COntents

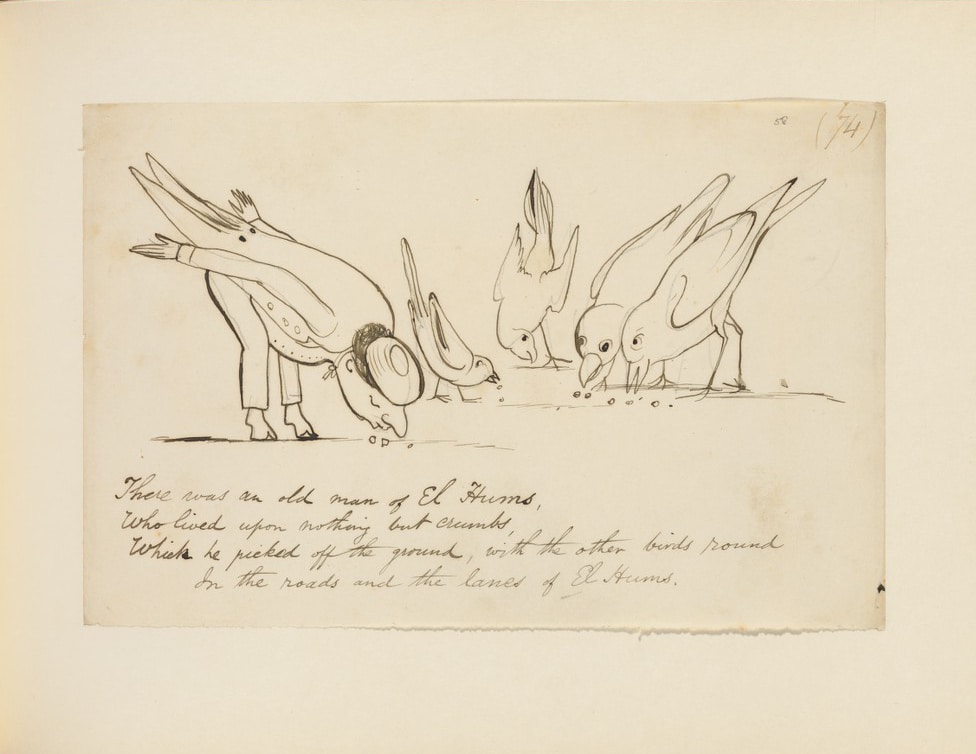

Edward Lear was somewhat of a paradoxical individual whose art reflects a diverse array of interests, and reveals a personality that would not be constrained by the parameters of a singular genre or technique. Rather, as a landscape painter, Nonsense-verse poet, scientific illustrator, and traveler, Lear refused to confine his creative production to a singular discipline. As a result of his prolific and expansive career, there are a number of avenues by which people often become acquainted with his work. In fact, for those who initially encounter the artist through his Nonsense lyrical poems, by contrast, his highly detailed scientific illustrations of animals seem almost antithetical to the playful disorder of the former works. Similarly, for those of us who discover Lear through his highly naturalistic zoological lithographs and landscape paintings, his guileless caricatures and Nonsense verse frame him as somewhat of an oxymoron.

Early Years and Cultural Influences

The varied nature of Lear’s artistic life was likely fostered by his lack of formal training in art or natural history, which may have cultivated in him a diverse array of interests, and a unique approach to the subjects he breached. Additionally, his art reflects several of the fundamental interests and concerns that surfaced in 18th century England. Firstly, the interest in collecting, naming, and categorizing exotic species, and secondly, the concern over Charles Darwin’s proposal of evolution. Through his scientific illustrations of birds and his Nonsense verse-drawings, Edward Lear ponders the dynamism and instability of nature.

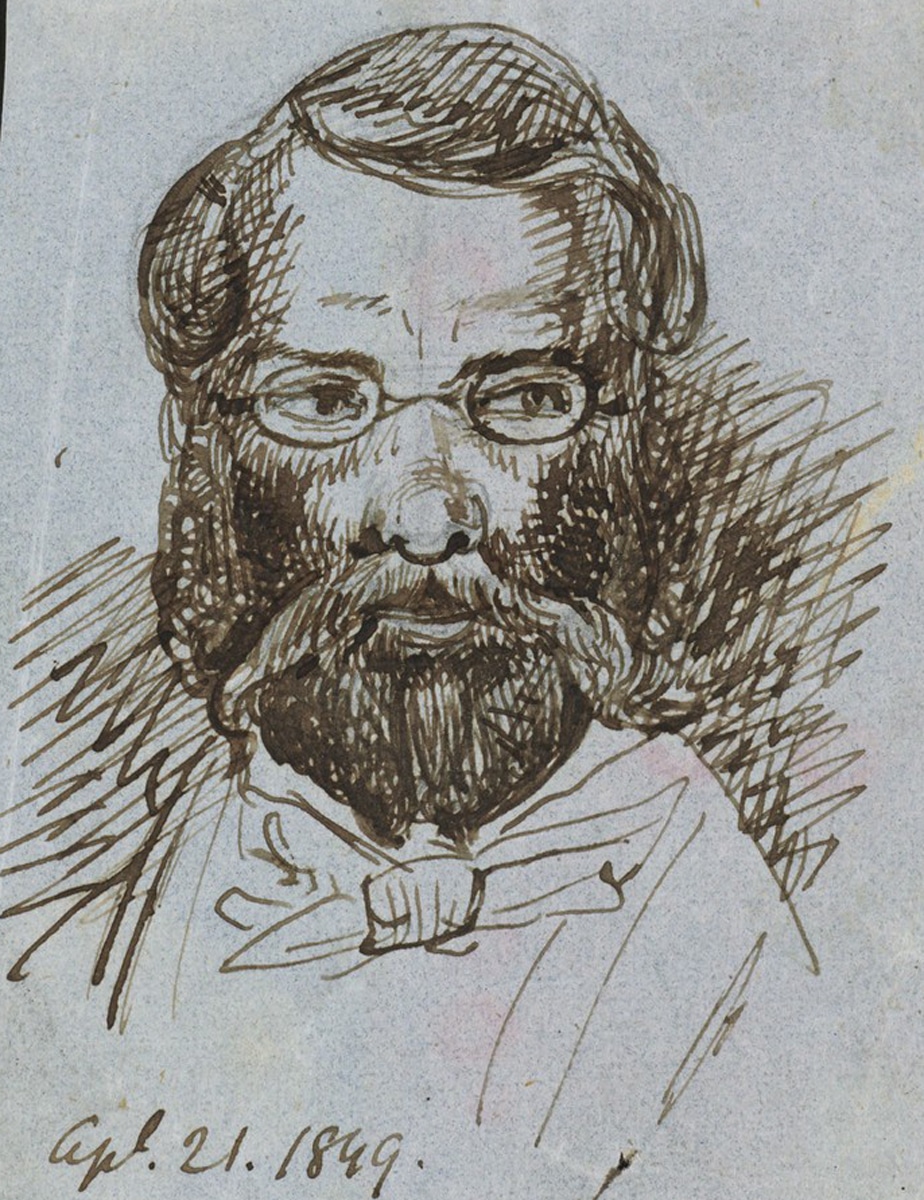

Born in 1812 as “the 20th of 21 children,” Lear began sketching at a young age (Susan Hyman, Edward Lear’s Birds, 12). At 15 years old, Lear recalls his initial success at monetizing his creative endeavors; “I began to draw, for bread and cheese about 1827 but only did uncommon queer shop-sketches — selling them for prices varying from 9d to four shillings; colouring prints, fans; awhile making morbid disease drawings, for hospitals and certain doctors of physics” (C.E. Jackson, Bird Illustrators, 32). Driven by necessity, Lear developed a unique approach to viewing and rendering the world around him.

Illustrations of the Family of Parrots

Lear’s first ornithological project, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, completed at the age of 18, demonstrates his ingenuity. This monographic project focused on a singular family of birds, and as C.E. Jackson explains “To portray all the members of one family of birds was a new idea” (Bird Illustrators, 33). More often, artists of this time narrowed their scope of inquiry to geographical regions or some broader parameter, but to create a visual monograph of a single family of birds was novel. In fact, naturalist-publisher John Gould would later adopt this blueprint for his own folios.

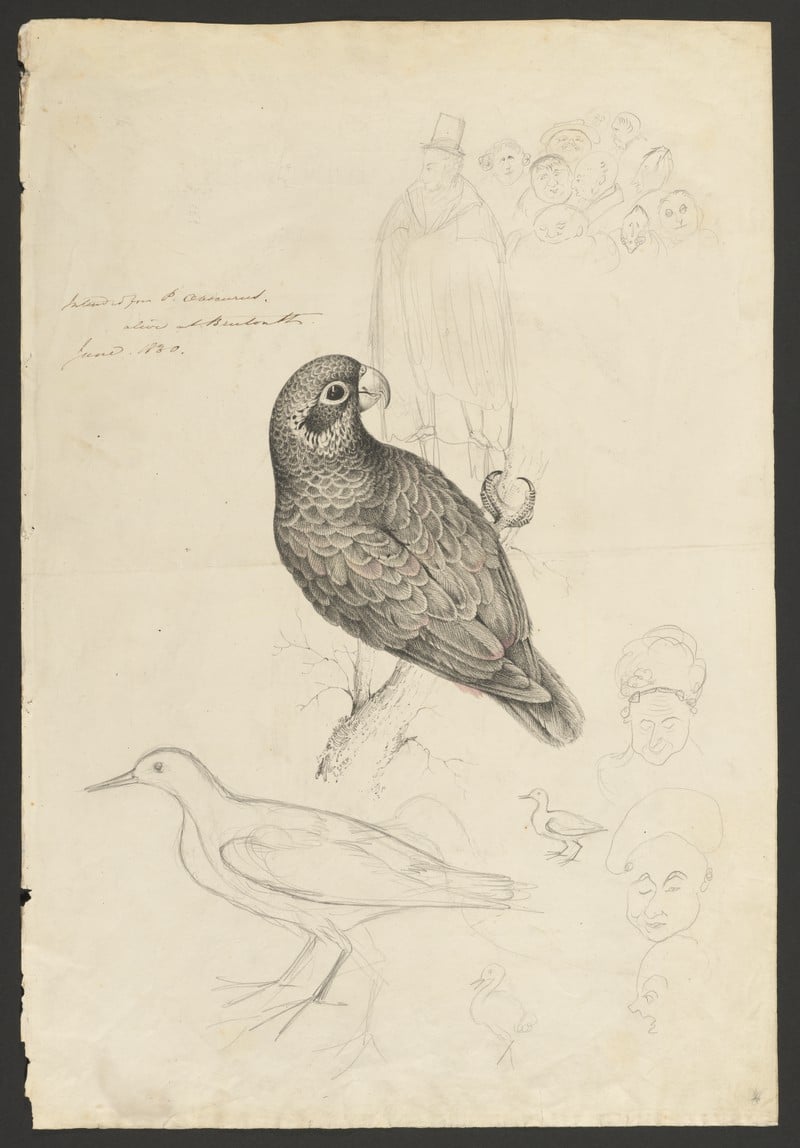

Routinely sketching parrots in the Zoological Gardens at Regents Park, Lear soon became somewhat of a spectacle to be viewed alongside the feathered display. Not one to be surveyed without retribution, Lear often sketched unflattering portraits of the nosey onlookers in the margins of his paper. Take for example one of his early sketches of a parrot, pictured to the right, in which we see a graphite and watercolor illustration of a parrot against a backdrop of curious and ogling faces. The bird itself turns its head to look at us as though to share an inside joke or clever remark, undoubtable aimed at the oblivious onlookers. These sketches, which Lear developed over the course of several years, were then translated into lithographs and issued to subscribers of his folio Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots.

Watercolor and graphite sketch of the Salmon-crested Cockatoo

Houghton Library

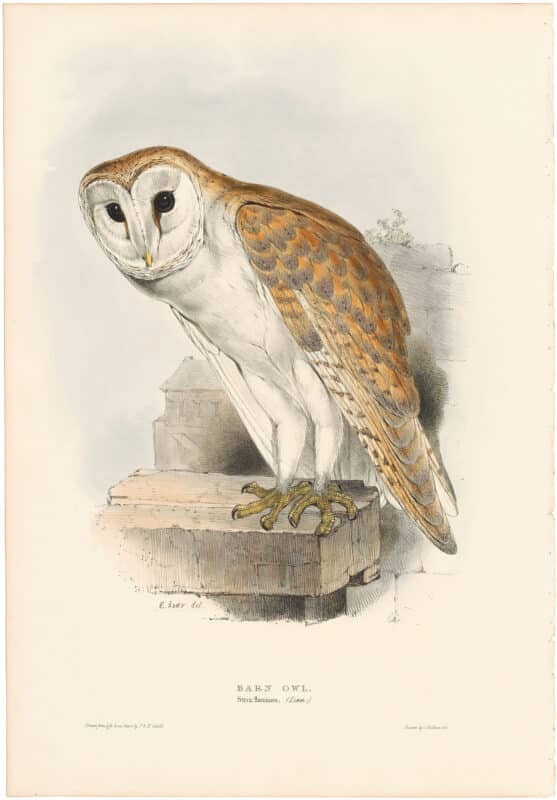

Printing the Folio

The lithographs, executed by Lear and printed by Charles Hullmandel, retain the immediacy and spontaneity of the artist’s hand in a manner that was difficult to ascertain through contemporaneous printmaking methods, such as engraving. Instead, Lear drew his parrots directly onto the lithographic stone, which was then treated, inked, and printed. The image above depicts Lear’s field sketch of the cockatoo, which was then printed (in reverse) through lithography, as can be seen below. This method of production emphasizes the birds fluidity of movement while retaining the intricate detailing of their feathers. Moreover, Lear used predominantly live specimens as reference material for his sketches, which was an uncommon practice for scientific illustrators at this time.

Pl. 1, Salmon-crested Cockatoo

Illustration for the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots

Take for example Pl. 1, Salmon-crested Cockatoo in which we are greeted by the flamboyant bird who, upon seeing us, gently bows his head in greeting. Rendered from a ventral vantage point, the cockatoo appears regal and brimming with personality. Its coyly elevated claw, coupled with a slight nod, and direct eye contact imbue the bird with a sense of life and charisma. The branch bearing the resplendent bird is rendered with less detail than it’s magnificent occupant, and begins to fade in color and contour towards the outskirts of the composition. As a result, our focus is lent solely to the bird who stands out against the sparse background.

As mentioned previously, collecting exotic birds and animals was popular particularly among the lesser gentry in England. Similarly, an illuminated book displaying extraordinary and foreign species was well suited to the tastes of the more affluent class, as the profitable sale of Lear’s Parrots demonstrates. In fact, Lear’s folio reflects the collecting habits of many wealthy Europeans in the 18th century who sought to outfit their cabinets and menageries with exotic naturalia as a display of their knowledge, worldliness, and wealth.

Notable Contributions and Collaborations

After the success of his initial venture, Lear continued to work with ornithological subjects and contributed to the folios of other artists including John Gould, Sir William Jardine, and Thomas Bell. Notably, Lear supplied John Gould with illustrations for several of his projects including The Birds of Europe, A Monograph of the Ramphastos, or Family of Toucans, and is even noted as having supplemented Gould’s illustrations for Darwin’s account of The Zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (Bird Illustrators, 37). Lear’s exposure to Darwin’s proposal of the mutable and evolutionary foundations of nature may have caused him to reconsider the boundaries between species, the nature of the body, and physicality itself. Reverberations of these consideration surfaces in his comical illustrations began while a resident at Knowsley Hall.

Unfortunately, at the young age of 24 Lear’s eyes failed him, and in 1836 he left England and spent the rest of his life writing nonsense verse, travel accounts, and painting landscapes.