Birds and Animal Art

“A Transcript from Living Nature”

An overview of the structural blueprint underlying Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology

Alexander Wilson is an enigmatic figure whose biography is as intriguing and indecipherable as his prints. After being exiled from Scotland at the age of 20 for writing a satirical poem about the management and labor circumstances at his place of work – a weaving mill – Wilson settled in Philadelphia where he pursued a number of trades. After dabbling in teaching, printmaking, and surveying, Wilson, at the age of 40, learned to draw and embraced birds as his primary subjects in his artwork. With the aid and encouragement of his friend Alexander Lawson and mentor William Bartram, he then set out to record the avifauna of America in a project to be titled American Ornithology.

American Ornithology

Published in nine volumes between 1807 and 1814, American Ornithology contained 76 plates in which 262 species of birds were depicted. A text describing the bird’s habits, diet, anatomy, and habitat accompanied the hand-colored engravings elucidating on the species shown. Though Wilson’s project has historical precedent in the work of George Edwards and Mark Catesby, with whom he shares stylistic similarities, his endeavor was unique in that he sought to portray the avian life of all of America. For this reason he is often called the “father of American Ornithology” because of the scope and breadth of his opus. Significantly, Wilson introduced the Linnaean system of taxonomy to the States and was the first ornithologist to present “any indication of the abundant bird life of the western United States” (Alexander Wilson: Naturalist and Pioneer, Robert Cantwell, 142).

Curious and endearing, Wilson’s depictions of North American birds act as “a transcript from living Nature” (American Ornithology, Vol. I, Alexander Wilson, 6). Rather than utilize a phylogenetic or scientific organizational system, Wilson drew the birds – multiple to one sheet – as he encountered them in nature or through specimens he acquired from friends and natural history collections. In this way, the underlying blueprint of his American Ornithology is as much a transcript of his life and travels as it is a record of American avifauna. Oftentimes there will be a coherence cadence in an individual print that explains the species pairing, but at other times the bird pairings appear purely aesthetic or motivated by the geographical proximity of species. Consequently, Wilson’s opus reflects a fluid structure that morphs and adapts to meet the needs of the particular print and the species represented therein.

Take for example Plate 3, Gold-winged Woodpecker; Black-throated Bunting; Blue Bird in which we are presented with three different species suspended against a sparse backdrop. With fragmented twigs to stabilize them, the birds are postured aesthetically so that their movements complement each other in a manner that could be taken for amicable interaction. Additionally, the design element of the composition is abetted by the pleasing color combinations of the triad. In an attempt to captivate his prospective audience, Wilson sought to forefront depictions of more captivating birds in his first volume in order to secure subscribers for the latter volumes.

In contrast to Pl. 3 Golden-winged Woodpecker, et al., Pl. 60 Great Tern; Lesser T.; Short-tailed T.; Black Skimmer; Stormy Petrel purports an entirely different approach. In this composition we are granted a background consisting of a craggy coastline upon which five waterbirds are presented. With a flagrant disregard for scale and spatial coherence, Wilson captured the birds in a variety of postures and relational proximities that would not typically appear in nature. The Stormy Petrel appears to be flying straight towards the cliff face, the lesser tern hazards a vertical dive, meanwhile the Greater Tern, Black Skimmer, and Short-tailed Tern dominate what appears to be a diminutive cliff. Here, Wilson has presented us with a beautiful composition that, when analyzed, is also a logical conundrum. The primary uniting factor of this print is it’s geographical location to which all the depicted sea birds are native.

A similar disregard for scalar and spatial coherence can be seen half a century prior in the work of Mark Catesby, a self-taught artist who documented the flora and fauna of colonial America. The similarities between the work of Wilson and that of Catesby can be identified in Catesby’s 1754, Vol. 1 Pl. 72, The Turn Stone or Sea Dottrel and Appendix Pl. 20, Buffalo in which spatial, perspectival, and proportional notions are upended. In the former print, the Turn Stone appears to be casually stepping over a vertically oriented piece of flora as though existing on a separate plane. Likewise in the latter, the buffalo appears dwarfed by the massive flowering sprig. The similarity between the two artist’s work is not untenable because while frequenting the extensive grounds and library of his friend and mentor William Bartram, Wilson frequently encountered the work of Catesby.

Catesby’s 1754, Vol. 1 Pl. 72, The Turn Stone or Sea Dottrel

Catesby Appendix Pl. 20 Buffalo

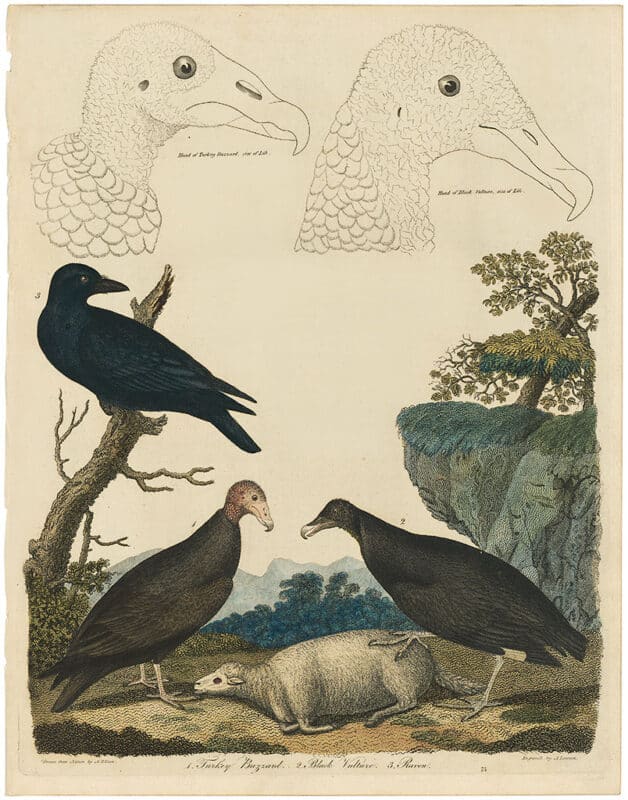

Wilson’s compositional schema morphs once again as can be seen in Pl. 75 Turkey Buzzard; Black Vulture; Raven. Here, in addition to the bizarre relative size of the raven with the carrion birds, Wilson has incorporated two anatomical diagrams to visually extrapolate on the structural aspects of the Turkey Buzzard and Black Vulture’s heads. The small text below each diagram identifies the bird and indicates that it is rendered at life-size. This print is unique in Wilson’s American Ornithology because of his incorporation of the anatomical close-up element. Unlike the aesthetic organization of the Pl. 3 The Golden-winged Woodpecker et. al, or the locationally specific uniting factor of Pl. 60 Great Tern et. al, this print focuses on birds of carrion who share the same diets and habits.

Sold for the “prohibitively expensive” price of $120, Wilson’s American Ornithology was a luxury item collected by wealthy individuals and institutions. While a monumental achievement in the history of ornithology in America, Wilson’s work is often overshadowed by his close successor, John James Audubon, whose renowned Birds of America proved an insurmountable corpus to contend with. However, just as Wilson’s work drew from that of Catesby, so too did Audubon reference material generated by Wilson as can be seen in the artists’ respective renderings of the Bald Eagle, which can be further examined in our article tracing The Evolution of Audubon’s White-headed Eagle. In conclusion, Wilson’s pioneering attempt to capture the avian life of North America stands as a valuable contribution to art and ornithology.