Ethnographic Art

Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign

The History of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Description De L’ Egypte and its Impact on Western Aesthetics

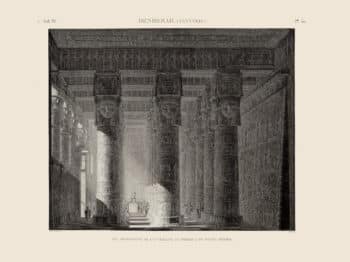

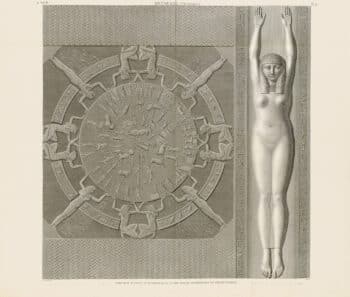

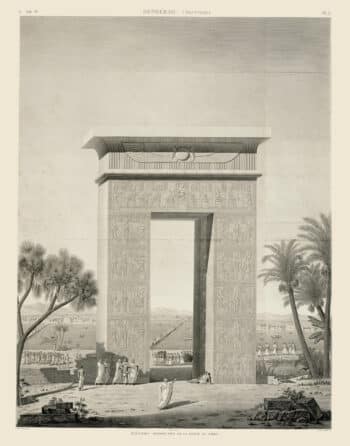

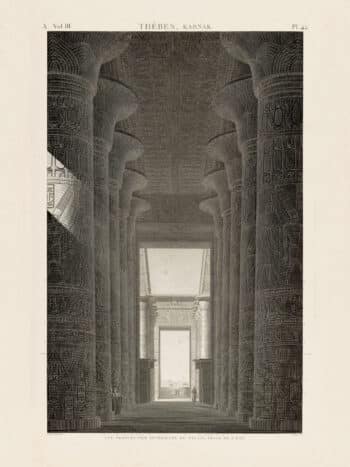

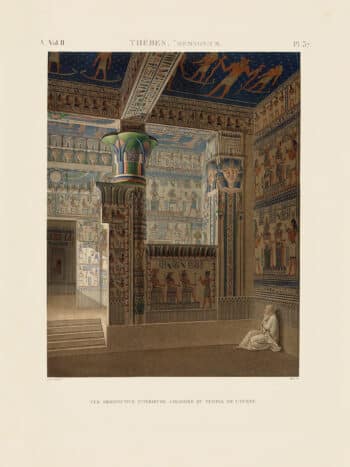

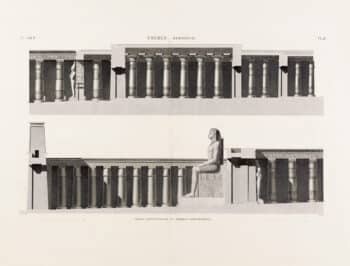

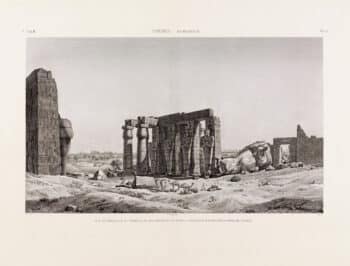

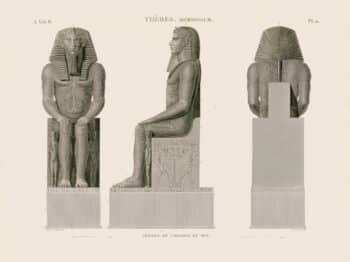

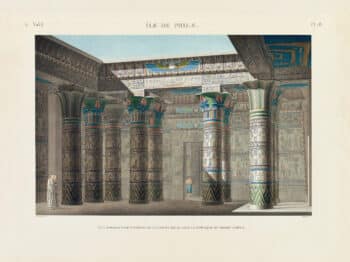

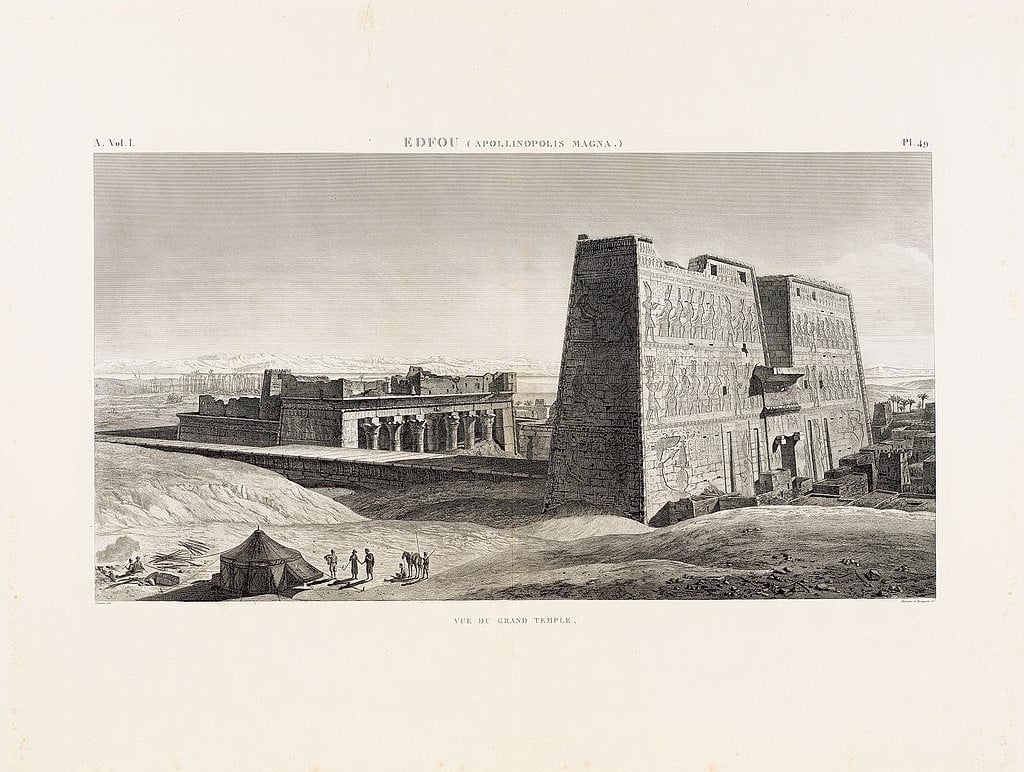

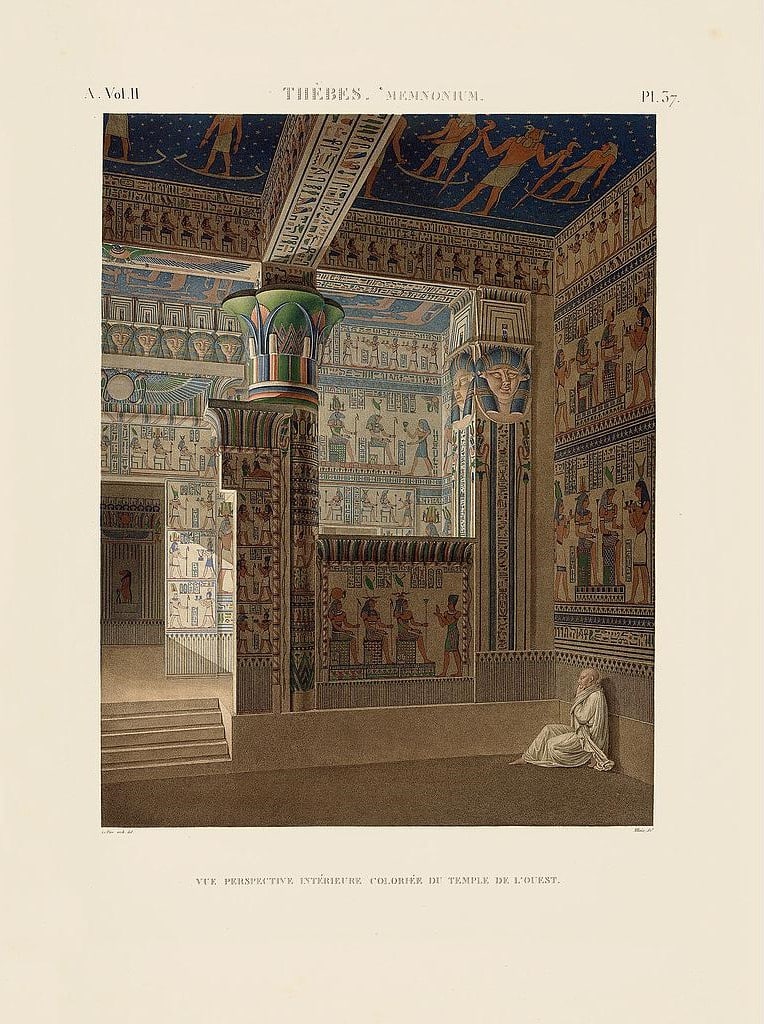

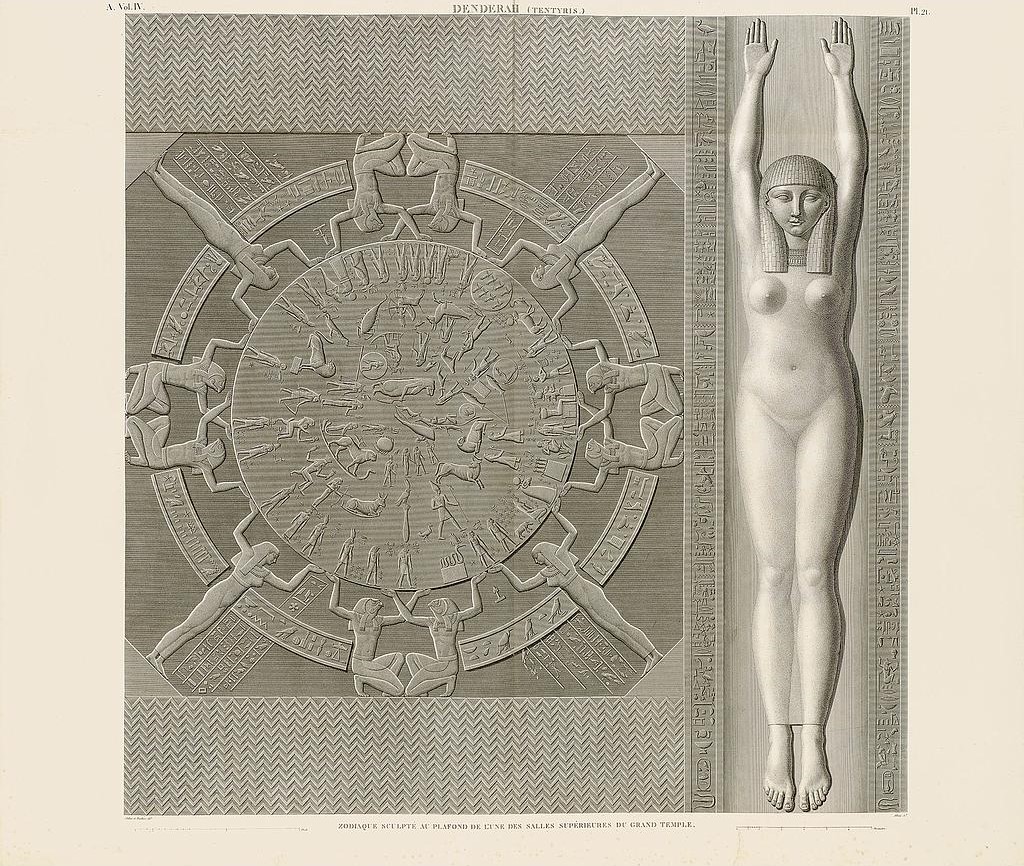

In his ambition to expand French borders, Napoleon traced the conquest routes of Alexander the Great and in 1798 led a military campaign to Egypt. From a political standpoint, the endeavor was a failure that resulted in the French troops surrendering to the British who were similarly in the midst of mapping out colonial conquests in North Africa. Despite Napoleon’s ill-conceived and poorly executed military campaign, the expedition was fruitful in its contributions to art and science through the production of Description De L’ Egypte. This publication, comprised of over 800 engravings, was vital in introducing Egyptology to Europe. As a result, for over a century after the initial campaign, Europeans and Americans were transfixed by the allure of Egypt.

Napoleon, who had a great interest in art and science, commissioned over 150 artists, astronomers, botanists, naturalists, physicists, doctors, engineers, and chemists to join him on his expedition and instructed them to explore and meticulously record the unknown wonders of Egypt. When describing Napoleon’s justification for his presence in Egypt, Gilles Néret suggests that “[His] ostensible motive was a generous one: to free the Egyptian people from the oppressive Ottoman Empire and its Mamelukes. The real motive was to found a French colony and make Egypt a province of the Republic, thus reinforcing French domination in the Mediterranean basin and even, perhaps, extending it into Asia; Napoleon dreamt of Alexander and Caesar and wished to emulate their glory” (Description De L’ Egypte, 2002, 12).

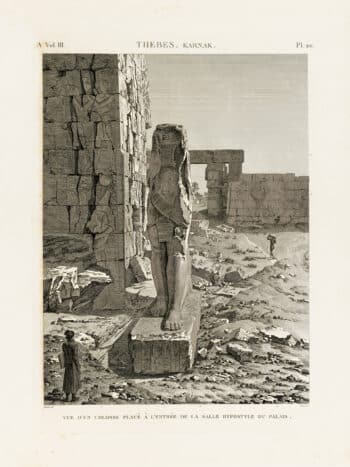

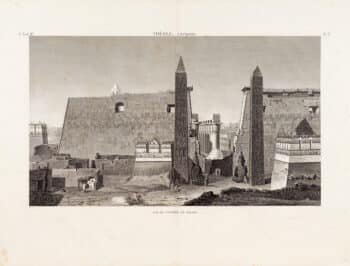

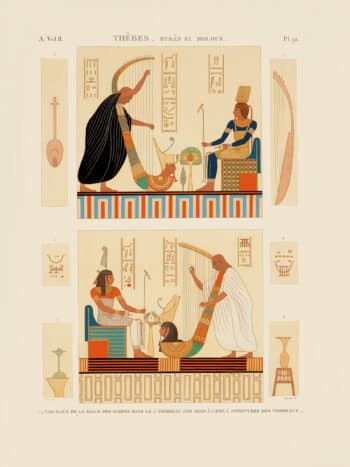

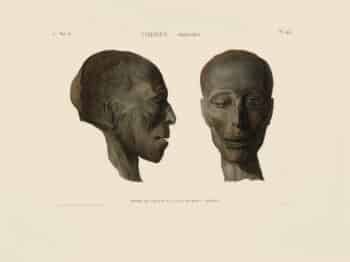

After Napoleon’s army successfully invaded Egypt, the savants set about systematically pillaging, collecting, and recording data and artifacts relating to numerous aspects of Egyptian life including art, medicine, agriculture, architecture, and natural history to name a few. Thorough notes were taken and sketches drawn before the smaller, more portable items were uprooted and prepared for exportation back to France. Likewise, a great number of colossal artifacts including large obelisks, statues of pharaohs, and carved edifices were taken from their original sites.

However, the purloined goods never reached French soil. Rather, while retreating back to France, Napoleon’s army was attacked and defeated by the British and Ottoman armies at the mouth of the Nile Delta. Consequently, the British demanded that the French hand over the pillaged goods, which notably included the Rosetta Stone (translated in 1822), but allowed the French to keep their notes and drawings. As a result, these drawings were translated into large folio prints and published with the accompanying text in Description De L’ Egypte (1809 and 1830).

While Napoleon’s campaign was an abject failure from a political and economic perspective, it was successful in renewing interest in the study of Ancient Egypt. The Egyptomania that ensued after the publication of Description De L’ Egypte greatly influenced European and American art and material culture. Western interpretations of Egyptian symbols could be found ornamenting textiles, furniture, and architecture. As Sara Ickow suggests, “Egyptian motifs provided an ‘exotic’ alternative to the more traditional styles of the day.” (Ickow, Sara. “Egyptian Revival.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.)

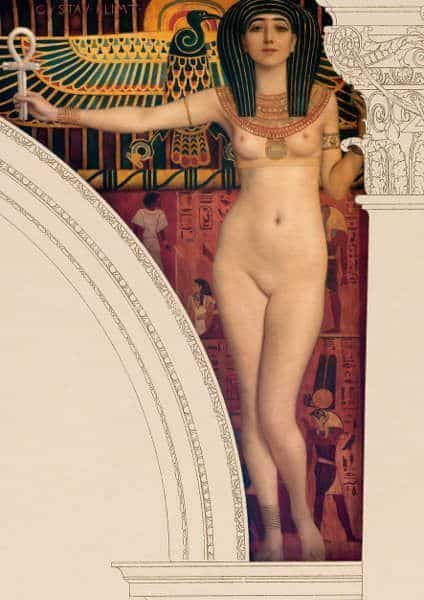

The prints from Description De L’ Egypte are unique in that they played an impactful role in initiating a movement that would last for over a century after publication. For example, several paintings by French classical artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, who was known for catering to the current tastes of the French public, depict exoticized visions of Egypt and its inhabitants. Similarly, the presence of obelisks in major cities such as Rome, Paris, and Washington D.C. indicates the global popularity of Egyptian art and architecture. Even into the 20th century, traces of Egyptian influence can be found in the art of Gustave Klimt and Alberto Giacometti.