Audubon Prints

Visualizing the Human Impact on the Natural World in Audubon’s Quadrupeds

An analysis of the characterization of human and animal relationships in Audubon’s Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

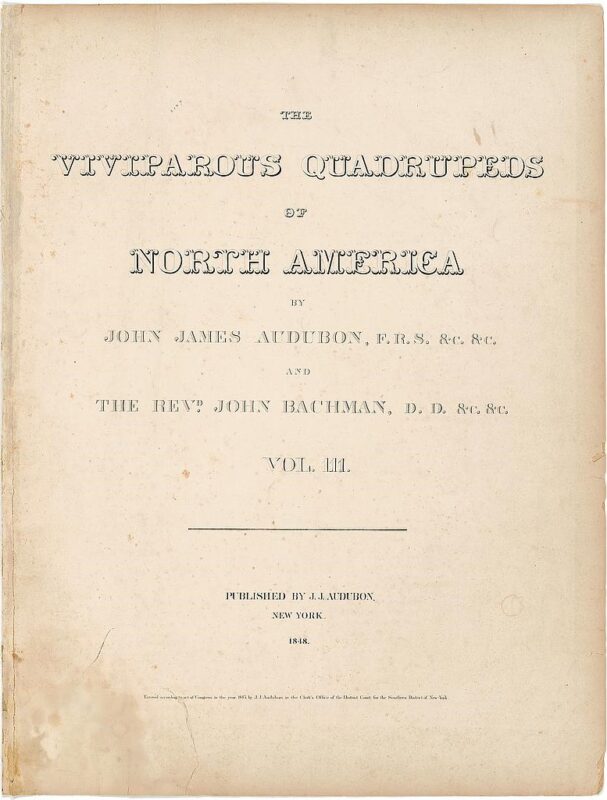

Unlike Audubon’s Birds of America, where human presence and impact on nature are infrequently illustrated, his Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America overtly depict the cohabitation, conflict, and outright aggression that characterizes his perception of human and animal relationships. Published between 1845 and 1848, Audubon’s Quadrupeds records a transitional time in which the wild and uncultivated American western frontier was becoming increasingly occupied by early settlers, fur traders, and loggers, to name a few. As a result, Audubon’s Quadruped folio was created through a lens of early American history at a point in which settlers were establishing relationships with the unfamiliar land and its occupants.

Initiated soon after the success of Audubon’s Birds of America, his Quadruped folio was to follow the same creative model as the former and chart the four-legged mammals of North America. With the aid of his sons Victor Gifford and John Woodhouse, and the collaborative effort of his friend the naturalist Rev. John Bachman, Audubon produced the largest lithographic folio printed on American soil at the time. Comprised of 150 hand-colored prints on Imperial-sized paper (22″ x 28″), the endeavor was one of the first serious attempts to visually document North American mammals.

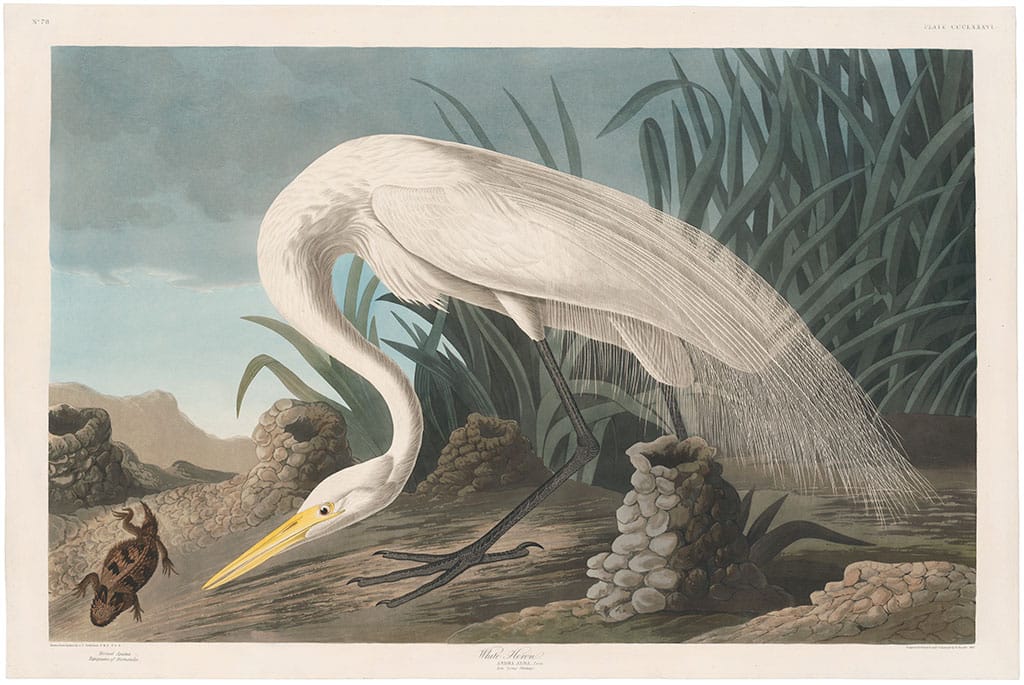

Audubon Havell Ed. Pl 386, White Heron

The Birds of America

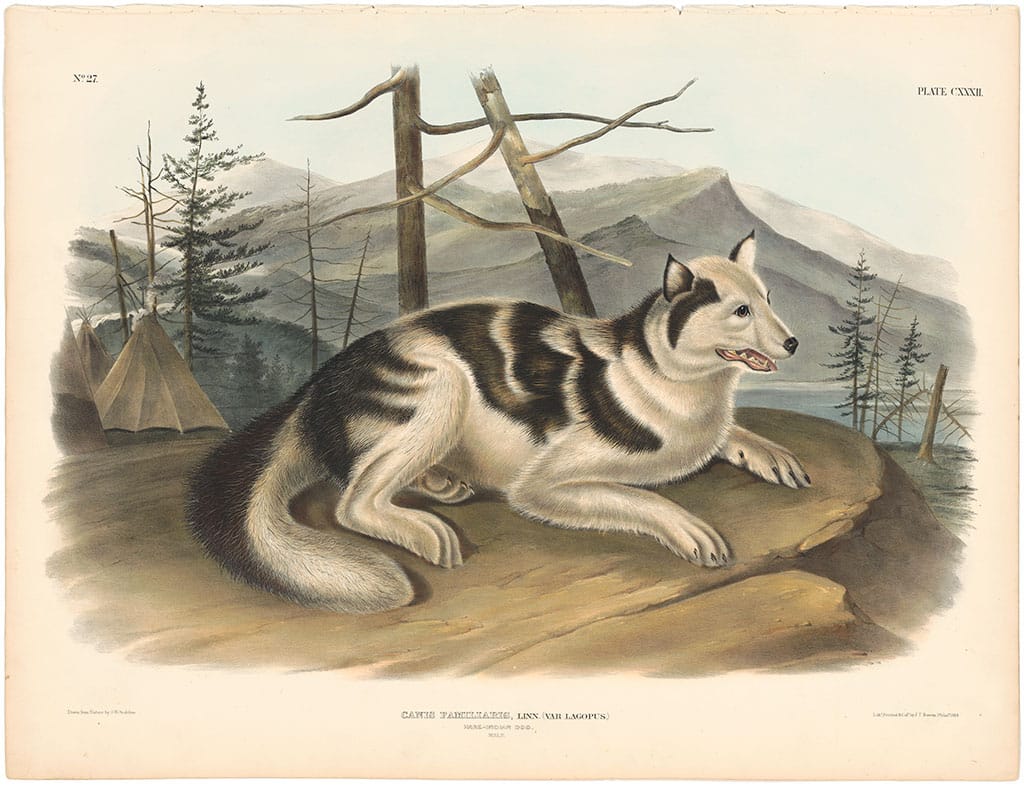

While Audubon’s Birds of America retains a romanticized view of nature in which the avian species are shown delightfully mired in their pristine and untouched habitat, such as in his Havell Ed. Pl 386, White Heron, his Quadrupeds are frequently shown occupying a shared environment with their biped companions. For instance, Pl. 132, Hare Indian Dog displays the canine relaxing in a clearing framed by trees and several tepees. As we can see, the dog is at ease, well-kept, and possesses no sense of urgency. The close proximity of the tepees as well as the relaxed demeanor of the canine suggests that it holds a harmonious relationship with the humans. In fact, this domesticated dog breed was valued for its hunting capabilities and often shared a symbiotic relationship with its owner.

Audubon Bowen Ed. Pl. 132, Hare Indian Dog

The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

In stark contrast, Audubon’s Pl. 51 Canada Otter elucidates a human-animal relationship that is rife with enmity. In this print, we are confronted by a snarling otter who, driven to a state of frenzied madness by the pain of having its forepaw clamped in the iron teeth of the trap, bears its teeth and hisses. The otter’s snarl reads as an accusation and the man-made trap leaves no room for doubt as to the identity of the perpetrator. The ferocity and unease with which we are confronted suggest that Audubon perceived this relationship as one lacking in harmony.

It is significant to note that at this time, otters, beavers, and mink were harvested for their pelts, and with the increase in commercial fur trading, the animal populations suffered. Audubon, though no stranger to hunting for sustenance, specimens, or otherwise, commented on the “senseless play” of hunting for sport. Somewhat contradictorily, it was at the behest of Pierre Chouteau, head of the American Fur Company, that Audubon and his companions traveled West on a steamship to gather information, resources, and specimens for the quadruped folio.

Audubon Imperial Bowen Edition Pl. 46 American Beaver

Audubon Bowen Ed. Pl. 33, Mink

Another instance in which the biped-quadruped relationship is reflected is in Pl. 23, Black Rat in which the rat assumes the role of pestilence. In this print, a gathering of rats ransacks the nest of an unidentified domesticated fowl. Before the yolky carnage of one egg has settled, another egg is plundered. The rats appear to snarl amongst themselves and exhibit no intent of leaving anything behind. There is a moralizing tenor to the artwork as Audubon presents the rats as thieving and greedy rather than a fact of life on the frontier.

In a similar vein, the Tawny Weasel Pl. 148 is depicted, not in its native environment, but rather as an encroacher upon the civilized domain of the farmyard. With its teeth embedded in the neck of an unsuspecting chicken, the weasel profits from the farmer’s carefully tended poultry.

There are a number of reasons why the human presence is more viscerally felt in the Quadrupeds than in the Birds. To begin with, the folio was a collaborative effort with varying creative visions at play. While Audubon and John Woodhouse drew the vast majority of the animals, Victor Gifford and Maria Martin took charge of designing and executing the backgrounds. As a result, there is less consistency between the prints of the Quadruped folio than those of the Bird folio. Moreover, the decades between the production of Birds of America and the Quadrupeds were highly transitional and mark a number of fundamental changes to the American landscape caused primarily by the migration West.

Audubon Bowen Ed. Pl. 148, Tawny Weasel

In conclusion, Audubon’s Quadruped folio observes the formation of relationships between early settlers and the native four-legged inhabitance of North America. Among these prints, we can trace a number of nuanced sentiments including symbiotic cohabitation, indifference, and outright hostility. In addition to standing as one of the first attempts to picture the mammals of North America, Audubon’s Quadrupeds offers remarkable insight into the swiftly changing landscape of 19th-century America.